Martin Luther King made his “I have a dream” speech on August 28th, 1963. It was held that day in honor of the anniversary of Emmett Till’s torture and murder on the same date, in 1955.

King murdered:

Then in 1968, after King himself had been murdered, Chicago hosted the most infamous of all party conventions: The Democratic National Convention of 1968, which became known as a “police riot” (per the Walker Report: “Rights in Conflict”) or “The Battle of Michigan Avenue.”

Sneak preview of Redlined

If you missed it, you can read a sneak preview of my book, in which I write about that tumultuous year of 1968 in my last blog post. The 50th anniversary of national events is usually a good time to reflect on them (as we’ve seen the thousands of articles and blog posts written about the Convention).

So my reflection on the “March on Washington” got set aside for a couple days. I’m revisiting it today on my regular blog post day of Thursday. I’ve posted this before, but it’s a central message of my book, so I want to use every opportunity to get it out into the world.

March on Washington, August 28, 1963

Millions of Americans heard King’s poetic demands for racial justice. Whites were either rapt in the power of his metaphor or furious and disdainful of his dreams. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI at that time labeled King “the most powerful and therefore, the most dangerous Negro in America.”

Whatever their position on Civil Rights, the vast majority of whites throughout the nation had no personal experience of integration.

That wasn’t true for my family. Just as the country was going through the throes of the Civil Rights Movement, my family was, for the first time, living with integration.

The March on Washington, Aug. 28, 1963

We watched King’s speech on television in our home in Chicago’s West Garfield Park neighborhood, the community where my paternal Grandparents had settled in 1912, raised their children, and where my dad and mother raised my two brothers and me, as well.

The previous fall of 1962, school boundaries had changed in our community to alleviate over-crowding of public schools in segregated black neighborhoods. The change brought an influx of African American students from south of Madison north into our mostly white community.

During that school year, white residents saw scores of African American children walking through the neighborhood. Whites panicked and began moving out in droves. In one year, the population of my former grade school was reversed, from 5% black students in the 1962 Tilton graduation class (my class) to 58% black in June 1963.

On June 22 1963, the first black family moved into a house on our street, in the 4200 block of West Washington Blvd. By the time King gave his speech, two months later, four houses had been sold to African Americans. A white diaspora was underway.

As Amanda Seligman quotes in her excellent book Block by Block, which examines the racial change in West Garfield Park, one anonymous “Homeowner” questioned the concept of integration as addressed in comments to our neighborhood newspaper, The Garfieldian. “Homeowner” wrote, “From your words one can only conclude that for you it is the time between when the first Negro family moves in and the last white family moves out.”

Chicago was (and still is) a notoriously segregated city. Blacks were all but invisible to whites as a presence in American society. No black actors were featured on any serious television show in 1963. (It would be two more years until I Spy broke ground in 1965 as the first television drama to feature an African American when Bill Cosby teamed up with Robert Culp). Virtually no blacks were in government. Magazine ads or billboards with blacks were non-existent (unless in an African American neighborhood or a magazine, like Jet or Ebony, geared specifically to blacks, where few, if any, whites would see them.)

The March on Washington and the Civil Rights movement in general put the injustices suffered by blacks front and center in the American consciousness.

But most whites, whether liberal-minded or racist, didn’t personally know any blacks. We didn’t either.

All that changed for us the summer of 1963. It was an era of red-lining, block-busting, and fear-mongering. Calls would come in the night. “They’re coming.” Click. No clue who called. Flyers appeared in our vestibule: “Sell now before it’s too late.”

We owned two 2-flats and frankly, we were afraid. As Isabel Wilkerson notes in her book, The Warmth of Other Sun: “It was an article of faith among many people in Chicago and other big cities that the arrival of colored people in an all-white neighborhood automatically lowered property values….The fears were not unfounded, but often not for the reason white residents were led to believe.” Prejudice aside, whites wanted out before they lost their property investment. In two months, four houses on our block were sold to blacks.

We stayed.

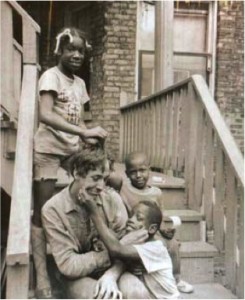

Nine years later, 1972, my younger brother, Billy, with our West Side neighbors.

Within days of the first blacks moving onto our block, the son in the family, Junior, and my brother, Billy, began playing together at each other’s houses. Martin Luther King’s dream, of “one day… little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white girls and white boys as sisters and brothers,” had come to pass on our block as a result of integration. My white brother and black Junior had become fast friends

The integration of our neighborhood wasn’t all brotherhood, sweetness, and light, however, and it would be a lie to pretend all prejudice disappeared, that no conflict emerged, and everyone lived in harmony. Still, what King envisioned in his speech at the March on Washington–the opportunity to forge friendships beyond racial stereotypes–had come to pass as a result of our integrating neighborhood.

I welcome your comments.

This post is similar to one originally posted on the 50th anniversary of King’s Dream speech.

Buy now: Redlined: A Memoir of Race, Change, and Fractured Community in 1960s Chicago

Indiebound Barnes & Noble Amazon

Hi Linda,

I appreciate your honest, courageous and humbling experience. Integration is a concept, for me not a reality. I appreciate you Linda, best wishes always.

Dekalb Walcott

Thanks for dropping by, Dekalb and for your comment. Integration didn’t last long in our neighborhood in any kind of equal numbers. Whites fled, and within a year we were among the few whites left. I understand where you’re coming from re integration. All the best always — Linda