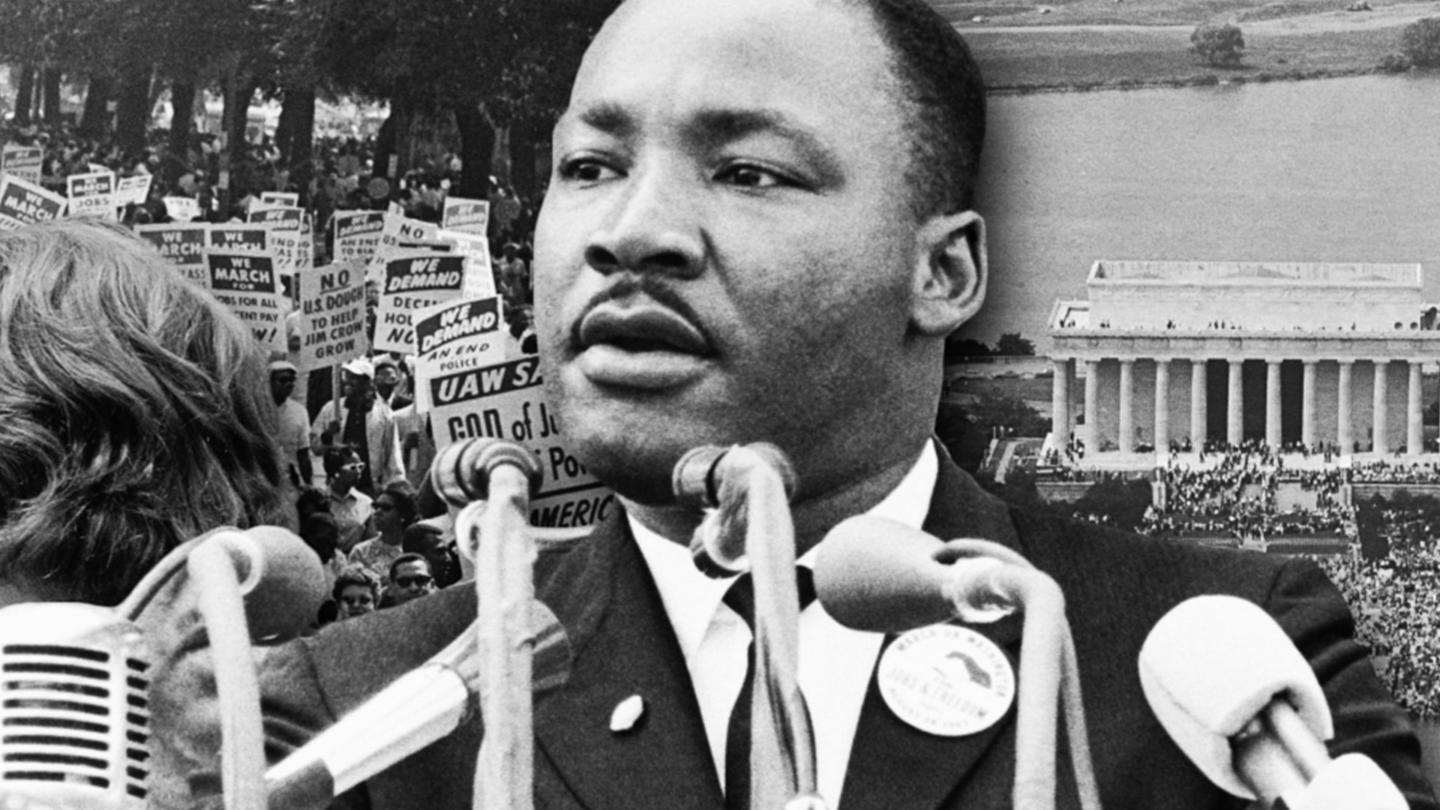

Is the work of the great Civil Rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., over? I hear from many frustrated white folks something akin to: Hey! That was 50 years ago! We took care of civil rights. We passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 fifty-five years ago. We had affirmative action! Blacks just haven’t worked hard enough to reach the same level of success as white people. If they’re still complaining, it’s their own fault. (Have any of you readers heard similar cavils?)

The fact is that the systematic (and systemic) undermining of Black wealth and achievement, the excess incarceration of Black men, and the continued segregation of our cities has made it all but impossible for African Americans to achieve the financial well-being that whites enjoy in disproportionate numbers. On Martin Luther King Day, I hope you have a few moments to read my thoughts about this disparity and see the list of a few books I’ve read that opened my eyes to more than I’d ever known about the Black experience as I completed research for my book.

The fact is that the systematic (and systemic) undermining of Black wealth and achievement, the excess incarceration of Black men, and the continued segregation of our cities has made it all but impossible for African Americans to achieve the financial well-being that whites enjoy in disproportionate numbers. On Martin Luther King Day, I hope you have a few moments to read my thoughts about this disparity and see the list of a few books I’ve read that opened my eyes to more than I’d ever known about the Black experience as I completed research for my book.

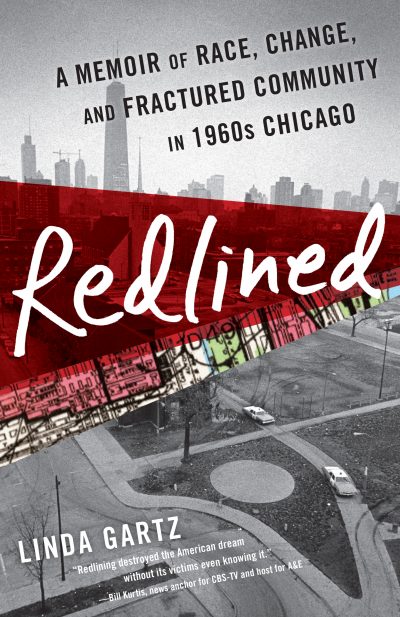

Redlining

I’ve presented to dozens of groups about my book, Redlined, and I’ve talked casually to many people, of all ages, about the federal government’s policy of redlining (denying any kind of loans to communities with even one black resident, a formal policy in place from 1933-1968). The Federal Housing Act was finally passed just days after King’s murder, in 1968.

Despite the fact that the FHA made discrimination illegal fifty-two years ago, Whites today, with the same financial profile as Blacks, get three times as many mortgages (Latinos are also left behind). See this PBS/Reveal study from Feb. 2018: Struggle for black and Latino mortgage applicants suggest modern-day redlining

Few Americans of any age can define “redlining”

What has struck me is that the vast majority of people I speak with don’t know what redlining really means (most people I’ve met under the age of fifty, both African Americans and Whites, have never even heard the term and those over fifty have only a vague notion of its meaning and impact. Virtually no one realizes it was a policy enacted by the federal government and written into the FHA’s (Federal Housing Authority) underwriting manual, quoted here: “Inharmonious racial groups should not live together.”

BlackVeterans denied access to GI Bill

In its wisdom to enforce this goal, the FHA refused to give mortgages to African Americans. As a special boost to keep Blacks from having the advantages Whites had, returning Black World War II veterans were denied access to the GI Bill!

Black Farmers denied loans

Southern Black farmers, couldn’t get loans to buy seed or equipment early in the season as could their white counterparts. How convenient for the banks to then foreclose on Black-owned farms! It’s all part of the same insidious racism embedded in our society. America denied African Americans the potential to build wealth as was afforded to White Americans, whether in rural or urban communities or even after serving our country in war.

Students don’t learn about redlining

We should all be aware that American history, especially school textbooks, have done an abysmal job of teaching young people for generations (including mine) anything that’s true about the Black experience. Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law, said in a presentation that the most widely used textbook in America contains one sentence about redlining, and it’s written in the passive tense. Something like, “African Americans found themselves in segregated neighborhoods.” Right. “. . . found themselves,” as if plopped there by aliens.

Students may learn about Martin Luther King, but details of the entrenched, structural policies that kept Blacks from participating in the bounty America offered to Whites are often hard to find.

States customize textbooks to promote a viewpoint

To make matters worse, each state has the right to excise or introduce material into textbooks as it sees fit, to meet the conservative or liberal viewpoints of its residents. Here’s an excerpt from a January 13th interview (by Audie Cornish) on NPR of Dana Goldstein (NYT’s reporter) about her five-month research and analysis of social studies textbooks from California and Texas:

Dana: Well, race was a theme that emerged in the coverage. And the way that the suburbanization of the United States in the 1950s is told is quite different between the two states. California requires children to learn about housing discrimination against African Americans and other groups. The story in Texas is very different. It doesn’t ever say in these books that the suburban dream was not accessible to African Americans because of housing discrimination.

CORNISH: What does it say instead?

GOLDSTEIN: It says that some people left the city because of congestion or crime. And those types of words are racially coded often, but it does not explicitly talk about race.

Basically, Texas is purposefully lying to its students (at least not teaching true history) to keep its conservative population happy and its students ignorant. We know there was housing discrimination against Blacks. Why in heaven’s name does Texas want to dissemble about this provable fact? These kids will grow up to be people who can’t/won’t accept the truth about decades-long discrimination and therefore, will reflexively not want to believe it.

I think the best way to honor Dr. King’s legacy is to suggest just a few of the books I found most enlightening in my journey to overcome the dearth of information in my education and upbringing about what our African American citizens have endured and been denied, from housing discrimination, Jim Crow, and the Great Migration to the present-day mass incarceration of Black men. I hope that one of them may find its way onto your reading list too. (Note: I’m including a link to Amazon to purchase these books, but if you can support your local independent bookstore, even better!)

The Warmth of Other Suns: the Epic story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson. A truly monumental work, using the stories of real people who escaped the Jim Crow South

The Warmth of Other Suns: the Epic story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson. A truly monumental work, using the stories of real people who escaped the Jim Crow South

Family Properties: How the Struggle Over Race and Real Estate Transformed Chicago and Urban America by Beryl Satter. Satter’s book uses her father’s archives and her own deep research to write about how redlining and blockbusting denied loans to Blacks in her community of North Lawndale, just south of my Chicago neighborhood of West Garfield Park. It applies to countless American communities.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander (see also the 2016 documentary by director Ava DuVernay, Thirteenth, based on this book, exploring the “intersection of race, justice and mass incarceration in the U.S.”

Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side by Eve Ewing. A University of Chicago sociologist, poet, and artist, Ewing links the struggles of Chicago Public Schools with racist housing policies.

Block-by-Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy in Chicago’s West Side by Amanda I. Seligman Seligman’s book is the first that introduced me to the policies that determined the fate of my childhood neighborhood. I remember vividly many of the policy decisions she describes in this book and their effect on my family.

Happy reading on this day to honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the man who used peaceful protest to bring attention to and help enact needed change in race relations in America. We’re not done yet, fifty-two years after his murder.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.