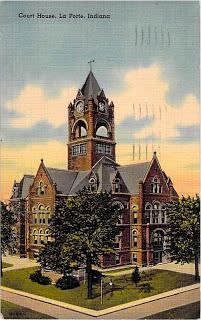

In the post, Explosive News, we heard that my dad, Fred, a chemist, quit his job with Lanteen to make almost double the salary as a blasting powder blender at the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant in LaPorte, Indiana. He started the job on March 30, 1942.

After Lil’s Easter post on April 5, 1942, she didn’t write for several weeks, until she made this startling entry.

May 16, 1942

Fred lost his job in Indiana through no fault of his. He felt so blue, poor guy, particularly over the injustice of it all. One thing Fred did find out through this experience is that he could fight back against any odds. He didn’t give up until he found out why he was canned.

[Mom also turned to shorthand in this entry, discussing what she understood about the dismissal (revealed below)––but clearly wanting to keep her thoughts hidden, perhaps for the same reasons Fred was fired? Thank you to Sandy Arnone, blogger extraordinaire at Spittal Street, for helping me decipher sections of Mom’s shorthand].

This is a tale about being “the other,” during war, even as a United States citizen. Most Americans know about the shameful injustice perpetrated against Japanese-American citizens during World War II. More than 100,000 were rounded up and sent to “internment camps.”

But many are unaware that thousands of German-Americans also suffered this knee-jerk discrimination. Internment camps were set up to hold not only Japanese Americans, but also those with Italian and German heritages.

My father became victim to anti-German bigotry, despite the fact that he and his brothers were natural-born American citizens and both his parents had attained American citizenship around 1920. A further irony is that my father’s parents had no affiliation to Germany: they were from Transylvania, in Romania after WWI, ethnic Germans whose ancestors had emigrated from Alsace in 1770 (my grandfather’s side) or had been driven out of Austria in the 19th century (my grandmother’s side), the latter because of religious bigotry against Lutherans.

Dad had often told the story of how he was fired, without warning, from the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant, just two months after starting, but I recently found a letter that detailed his reaction to this traumatic experience as it unfolded.

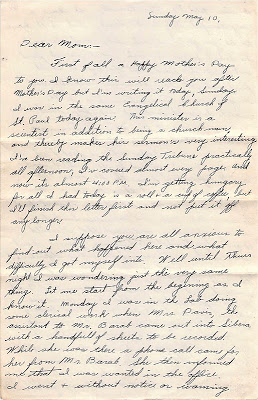

On Sunday, May 10, 1942 (Mother’s Day), Fred wrote an eight-page letter to his mother and family, explaining his summary dismissal, the outright lies and run-around about the reasons behind his firing, and how he fought back to get at the truth and clear his and his family’s name. As Lil notes in her diary entry, he tapped a reservoir of confidence he hadn’t realized he possessed.

These are the key events in the story, all culled from that May10th letter.

On Monday May 4th, Fred was in the lab at the Kingsbury Plant when Mr. Barab, one of his bosses, called Fred into his office. With no explanation nor prior warning, Barab told him, “I have a very painful duty to do, Gartz, but I’ll have to let you go.”

“Why?!” Fred was flat-out blindsided.

“I don’t know.”

“How can I find out?”

“Perhaps at the personnel department.”

Barab gave Fred a “termination slip” so he could pick up the pay due to him. A security guard escorted Fred to Personnel, to ensure he turned in his identification badge.

Fred refused to give up the badge until he had a full explanation as to why he was being fired. No one was available in personnel except a Mr. Vail, who “was reluctant to give out any information” and told Fred, “You’ll know what’s wrong.”

“I certainly don’t know what’s wrong!” said Fred. “This entire department is incompetent if I can’t even get the truth!” For my dad, who hated confrontation, this aggressive statement reflected the level of outrage and frustration he felt.

Fred wrote, “Mr. Vail got sore and told me to leave. I said I wouldn’t until I found out who could give me information leading to my dismissal.”

Vail replied that nothing could be done, but implied that the trouble had to do with the quality of Fred’s work, which Fred knew “was patently untrue.”

“My work has always been satisfactory,” he told Vail, who summarily dismissed Fred from his office.

Going back to the Personnel office, the security guard pressured Fred to give up his badge because his day was up and he wanted to go home. “I’m not leaving until I find out why I was fired,” Fred told him. “It may be a little overtime for you, but to me it’s a job.”

In my goal to keep these posts readable within a few minutes, I’m breaking up this story into parts. I’ll continue the story of how doggedly Fred had to work to track down the real reason for his firing next week with “An F.B.I. investigation of the whole family?!”

My mother was four when the family emigrated from Germany in 1926. She graduated from High School in 1940 and could not find a job except as a clerk working in a bakery.

Her father had died accidentally in 1936 and her mother had remarried in 1939, the only job she could find was a housekeeping job in an elementary school.

I often wondered if my grandmother remarried for convenience. That marriage lasted about thirty years, when she died.

Hi Linda:

I am enjoying your blog, a I told you at book group. You might want to read “Those who Save Us” Can’t remember the author’s name. It is a story of Germans who were Righteous Gentiles and the anti-German treatment they experienced when they came to the U.S. after the war.

Margaret

Linda, you are cruel! Talk about leaving us hanging… I’m wondering if the KKK was involved? They were very strong in Indiana.

My dad told me about his experience in WWI when because of his German name (his folks had been here since the mid 1800s), he was chased home repeatedly and tauted with anti German slurs. I fear some things don’t change.

Linda, in researching my mother-in-law’s family, I ran across a scenario where some of that German-Amrican family changed the spelling of their obviously Germanic surname, supposedly in solidarity with their American homeland and as a protest over what their ancestral homeland was doing during the war. However, with what you are reporting, it may be closer to the truth that their move was more out of self-defence than broad editorial comment about the war.

Your post on this topic is not only interesting, but a vital point in our history. Looking forward to the rest of this story!

I’m looking forward to the next post!!

Claudia, your family’s position had to be even harder–immigrating from Germany just 15 years before war broke out. Many married for convenience–especially if children were involved. A good spouse made life easier, if it wasn’t love at first, they often came to love and respect each other, if kindly good folk. Margaret, even the best intentions can’t save us from bigotry. What an irony. No, Candace, the KKK wasn’t involved in this case. Just regular folks under the influence of out-sized fear. Marian, my dad and brother experienced the same in WWI – beaten up on the way to and… Read more »

As you know, I live in Cincinnati — a city where a large percentage of the population traces its roots to Germany. Even here, the hysteria was so extreme that they changed the names of several streets because they had German names. German had always been taught as a second language in the public schools until WWI. I even heard a story where a high school senior was removed from class because of the perception that he sympathized with Germany. What’s interesting is that at the time, the U.S. was officially neutral. Tough times.

Wow. Reading that made me really angry for him. I had just heard recently (on The Daily Show) about the discrimination and camps for the Italians and Germans (I knew about the Japanese camps). My anger was for the way he was treated. Just unacceptable. I’m glad your dad stood up for himself!

I have been researching my husband’s family for about 25 years and his family came out of Austria sometime in the 1700s. I have not tried to trace them to their homeland because their SC lines are so vague, but they ended up the hills of East Tennessee and most of them seemed to stay there. I wonder if the prejudice and the fear and bigotry shown toward the German immigrants during WWI and WWII was more prevalent in the big cities? Does anyone know if it was rampant in the rural areas? It is such a vile and hateful… Read more »

It’s like what Agent K says in Men In Black: “a person is smart. People are dumb…” Once groupthink comes into play stupid things start to happen. This discrimination also happened during World War I and I’ve always found it disturbing…why didn’t people recognize that our country was built by immigrants? I look forward to seeing how Fred responds!

Dear Kathy, Cheryl, Judith, Heather, Thank you for your empathy with Fred’s situation and your own stories of discrimination. We all know that this kind of prejudice is a human phenomenon — visible from tribal warfare in Africa to ethnic cleansing in Bosnia — and in our own dear country, triggered by everything from war (think of how Japanese, Germans, and Italians were portrayed in the media during WWII– hideous beasts, engaged in unspeakable atrocities)–which then was associated with just good decent citizens of those ethnic backgrounds. Good judgment and common sense will be victims of a war mentality, so… Read more »

Fascinating! A wonderful account. Journals are our physical attachment to our ancestors. I will be following the progress!

Cheri,

I’m certainly finding out exactly what you say about journals. They are historical documents, telling the history of the time through the eyes of anyone willing to write (and assuming they keep and protect the journals). I am very lucky to have had a family that believed their lives were not only worth recording, but organized their documents in a reasonably logical way considering they weren’t archivists. Well, I guess they were!