In honor of Veterans Day, I’m posting “Words, War, Worry,” an essay I wrote honoring our servicemen and women and the mothers who love them and fret over their safety.

I think it’s apropos to re-post this article on November 9th because it originally appeared exactly fourteen years ago today on the front page of the Chicago Tribune’s Perspective section. Thanks to Charles Madigan, then editor of Perspective, for choosing my essay to accompany a visual array honoring those American soldiers most-recently killed at that time in the Iraq/Afghanistan War.

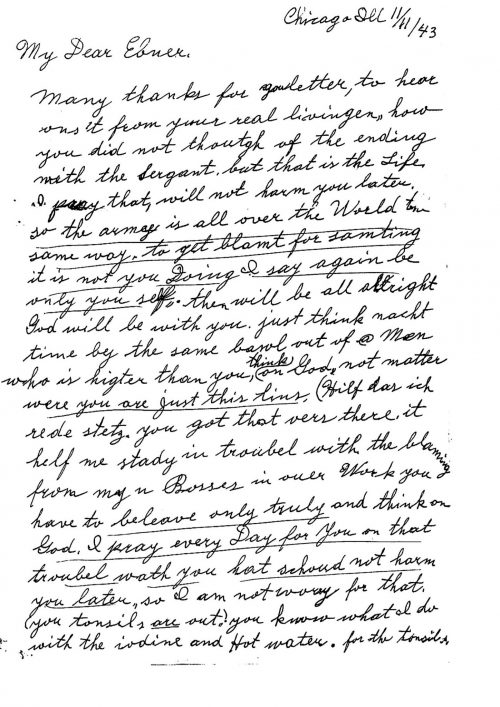

(Please note that dates related in the piece refer to when it was written in 2003). If you scroll to the end of the post, you’ll see a copy of the first page of my grandmother’s letter to her son.)

Words, War, Worry

ON THIS VETERANS DAY, thousands of mothers are aching with worry about their sons and daughters in uniform in foreign lands. Newspapers display photos of trained and tough young men and women, but the mothers know it was just yesterday that they held these warriors as children, cooked them a favorite meal, nurtured them through illness, advised them through troubles, and kissed away their sorrows.

It was no different for my Romanian immigrant grandmother 60 years ago.

Her youngest son, my father’s kid brother, 19-year-old Frank Gartz, was stationed at Stevens Point, Wis., with the 97th College Training Detachment of the Army Air Forces.

Ebner: I.D. while in training, about 1943

A year later, in 1944, he would be sent to Italy as a navigator, flying bombing missions in the last year of World War II.

Unable to “be there” for her child, my grandmother poured all the mothering she could muster into her letters, which remained boxed and buried in the dusty corners of basements and attics for decades. After my mother’s death in 1994, they came to rest in my garage for nine years until, finally, a nagging inner voice drove me to bring them to the light of day.

These long-ignored letters concealed insights into another era and, most important to me, into my grandmother’s mind. If they had been left unread, old family myths would have persisted, and a side to my grandmother’s personality would have remained unknown to me.

Gartz family photo, Jan. 1943, two weeks before Frank was drafted. L-R, standing: Dad (Fred), Will, Frank. Seated: Mom (Lil), Grandpa (Josef), Grandma (Elisabeth).

I remember Elizabeth Gartz as a hardworking, no-nonsense woman, long on will power but short on compassion.

That last impression melted when I began reading her heartfelt letters to her son, whom she called by his middle name, Ebner. They are all the more poignant because she had to write them in a foreign language– English. My grandmother was from Romania, but she was an ethnic German, and that was her native tongue. During World War II, it wouldn’t have done for a young American soldier to receive communication in German. More than likely, it would have jeopardized his standing, and perhaps even cast suspicion on his loyalty. Frank asked his mother to write to him in English.

After spending a long, hard day working with my grandfather in the many buildings they took care of as janitors on Chicago’s West Side, my grandmother would sit down, usually late at night, with a German-English dictionary by her side, struggling to put into words what was in her heart and mind.

One of her letters was written exactly 60 years ago this Veterans Day, on Nov. 11, 1943, then called Armistice Day. Despite the letter’s tortured syntax and misspellings of English written with a foreign accent, her devotion illuminates every page.

Lt. Frank Ebner Gartz, B-17 navigator, 1944.

In a Nov. 6 letter to his mother, Frank had described a punishment he had received as a result of an altercation with his sergeant over supposedly not following orders. “He got hot and so did I, and we said many harsh words to each other,” he wrote. His mother seems to nod understandingly when she writes back in her broken English, “So the army is the same all over the world. You get blamt for someting not your doing.” But then she adds some motherly advice, “Next time you get bawled out by a man higher than you, say these lines to God, ‘Help me to speak calmly.’ ”

She passes on snippets of family gossip–“Pa goes to the dentist with his teeth. One hat to pull out”–and she shares the empty-nester melancholy of a woman whose three grown sons are busy with their own lives. “I am so lonesome. I stand often looking at the three pictures and pray for my boys.” Like every mother separated from a child by wartime and training, she is desperate to hear from him. “Please write me as you can. I am glad for every bit.”

She inquires into his studies. “How you getting along with your school? Is it too hard or not too bad?” She looks after his social life–“You got goot fellow for your friend?”–and after his love life. A girl he was seeing had to leave the area where he was stationed, upon which she writes, “I am glad you hat a swell girl and had a goot time. I wish you a sweller girl.” She dispenses medical advice for his sore throat– “Use hot water and iodine”–and frets over his bout with dysentery, “Is your stomach weak? Watch what you eat.” She promises him a special meal. “I have a veal steak or round steak ready if you come home for week end. You will like it (I hope).”

She reports on the mundane–his at-home girlfriend, Cookie Karbach, has a cold–and the terrifying: their former Chicago Tribune delivery boy was shot down over Sicily: ” . . . broken arm, broken feet, broken back & collarbone,” she writes. Their pastor’s brother “was badly stabt and shot tru both shoulder and hip.” These stories must have struck fear into her heart, knowing that very soon, he, too, would be in combat. Throughout every letter, she turns to God for solace, “I pray for you morning and night.”

I see my grandmother’s letters as a kind of nurturing talisman, her desperate attempt to ward off the twin demons of fear and helplessness that stalk all parents whose children are in harm’s way.

Six decades later, mothers are still sending their soldier sons and daughters letters–and now, email [and texts]–filled with family and neighborhood news, encouragement, advice, love and prayer. Each holds the ardent hope that if mom can’t give “hands-on” care, perhaps these missives of mothering will keep danger and hostility at bay.

Below the Redlined image is the first page of a xeroxed copy of my grandmother’s letter. The underlinings are mine.

Find out what happened to Frank and our community. Redlined: coming 4-3-2018

This is a very touching reminder of the ties that bind. Linda you can Really tell a story. My boss when I was 16 yrs old just died recently. He was my brother’s brother in law. He was in Germany’s Navy Infantry (like our Marines) during WWll. I visited him last June and decided to thank him for his service. He had never been thanked for fighting for his country. Mostly he was jeered at because he fought for Germany. He moved to the US in the mid 50’s. He taught me my work ethic. He built up from nothing… Read more »

Hoo boy, this is late, but I wanted to thank you for your comment and your understanding that many have no choice when it comes to war. My best friend’s father-in-law was in the German Luftwaffe. What could he do when he lived in Germany? He came to the United States after the war, became a citizen, and was the kindest, gentlest man- especially with kids.

Dear Dayton, I apologize for the long delay in replying to your heartfelt comment. I understand what you’re saying here. One of my best friend’s father flew for the Luftwaffe in WWII. People don’t understand that these young men had no choice. If you refused to serve, you might have been shot – along with your whole family. That was kind and open-minded of you to thank him. History is written by the victors. It’s important to remember that our own US soldiers, who fought in Vietnam, often came home to hostility, jeers, and spitting – and THEY had served… Read more »

You never know what battle’s others may be fighting, always be kind. Always.

Thank you for your comment. You are so right!