Photo Credit: Chuck Wlodarczyk

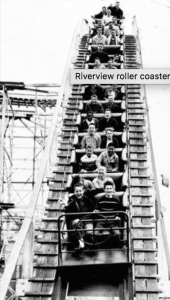

Chicago’s iconic Riverview Amusement Park closed fifty years ago, in 1967.

Riverview was a place of carnies and pink spun cotton candy; where the Bobs roller coaster careened around tight curves and plunged down steep tracks so fast that thousands of women’s clip-on earrings tore off–later to be displayed in a huge trunk on the loading platform.

Aladdin’s Castle–with its huge, cartoonish, somewhat sinister rendition of Aladdin, greeted visitors into a creepy “fun-house” that terrified me as a little child.

Chicago Tribune archives

On the Pair-o-chutes, we rose ever…so…slowly…up…up…up…The anticipation was a killer, not knowing when we’d hit the top. When we did, the chutes burst open with a gut-wrenching jolt, and we plummeted, leaving our stomachs somewhere along the way.

But there was a less amusing side to Riverview Amusement Park, one that was a perfect metaphor for racial attitudes common in Chicago, and most of the country, prior to the park’s closing.

It was the Dunk Tank.

The Dunk Tank had various names over the years, and today it’s shocking to think that, for decades, no one (at least not most white people) found them offensive: “the N—-er Dip, the Darktown Tangos, the Chocolate Drops, the African Dip, and finally the Dip.”

The dunkees were African American men. The dunkers were (almost always) white men. (In the accompanying photo, you can see a black teen or young man pulling back his arm to throw, but not many blacks visited the park). White men were never dunked.

Photo Credit: LivingHistoryOfIllinois.org

The black men sat on stools within cages, a target over their shoulders. They goaded white men passing by with insults like, “Hey Shortie, I bet you couldn’t hit the side of a barn,” or “Hey Buddy, that’s not the same girl I saw you with yesterday.”

It was understood that the very idea of a black man openly insulting a white man was so infuriating that the white men would buy ball after ball to get even with that “son-of-bitch” (as I heard many yell) and throw, veins popping out of their necks, with all their might at the target. If it was hit, the black man plunged into the water.

But the black men weren’t cowed. They gamely jumped back onto their stools and started in again on the same guy or the next passing white dupe, who, sure enough, bought more balls. Even as a young girl, it was obvious to me that the taunts from the dunk tank were intended to get the white men to keep spending their money. I couldn’t understand why the white guys didn’t get it.

Yet the white men’s over-the-top fury seemed mean (and frightening) to me as a little kid in the 1950s. I could see the racial division: white ball-throwers; blacks in the dunk tanks. I wondered if the black men felt bad (even though they laughed at and kept goading the whites), but I didn’t have a name for the discomfort I felt. I now realize the discomfort I felt came from sensing the racist nature of the game (though I didn’t have a name for it).

In the early ‘60s, a Pulitzer-Prize winning Chicago newspaper columnist, Mike Royko, decried the Dunk Tank as racist in one of his 1964 columns. He wrote the accussation less than a year after the August 1963 March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King had given his “Dream” speech. As the Civil Rights Movement gained steam, many white Americans were beginning to recognize the racism prevalent in just about every area of life, from housing to entertainment. Riverview closed the concession.

Just three years later, Riverview shut down. According to the book, Laugh Your Troubles Away, the main reason the park closed down was economic. When first built, Riverview had been “on the outskirts of the city,” but the park was now right in the center. “The land was worth more than the revenue the park generated, and it was sold.”

Chicago Tribune archives

My friends and I have nostalgic memories of the great fun we had at the park as kids in the fifties and sixties. As whites, we moved easily among the rides and concessions, our presence never questioned, blinders firmly in place as to the racism that the Dunk Tank represented.

Share some of your memories, or what your parents may have told you, about racism that was ignored, overlooked, or accepted in the past. What kind of ongoing racism do you see even if more subtle? What work is left to do?

**Quotes from Laugh Your Troubles Away, A Complete History of Riverview Park, Chicago Illinois. by Derek Gee and Ralph Lopez

For more detail, see “Riverview 1904-1967” from Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal

Some images from: Living History of Illinois dot com

IT WAS 1957 OR 58, MY UNCLE, COUSIN AND BEST FRIEND WENT RIVERVIEW ON OPENING DAY. AS I WAS TO YOUNG TO OPERATE THE ” BUMP EM” CAR WITHOUT AN ADULT , MY UNCLE RODE AND I BUMPED ” TWO TON BAKER ” PREMATURELY BEFORE HE CALLED FOR ACTION . IT PLAYED FOR MANY YEARS AND WAS MY FIRST TELEVISION APPEARANCE. TWO TON WAS MAD , BUT FUN WAS HAD BY ALL. DESPITE THE ” DIP” , I NOTICED SOME PREDIJUCED TENSION , BUT OVERALL FUN WAS HAD AT RIVERVIEW. I” LL NEVER FORGET. P.S. I WAS WONDERING IF THAT… Read more »

Hi Norman, Thanks for the memories. Yes, we all have a lot of fun at Riverview. What an interesting story you just told. Do you remember what station 2-ton Baker was on? You could google it, then reach out to the station and ask. It’s an interesting story – for them as well. We didn’t think much about racism back in the day. It just existed-as if a natural part of life. Not so for the many who felt its sting.

I always remember “two ton baker the music maker” but I don’t remember why. Was he just there for fun or is that what he was from? If you know the answer please let me know.

I remember Two-Ton Baker on TV too.

Hi Linda, I was doing some research for a memoir I’m writing and came across your post. I was raised in Lincolnwood in the 60s and 70s and don’t think I ever went to that park; but I do remember my mother, who grew up in Chicago, talking about it. She said how humiliating it must have been for a black man to agree to do that, and why people would be sadistic enough to engage in it. It made a big impact on me. Thanks for recording this; I think it’s important. I also wonder if any of the… Read more »

Hi Roberta, Riverview was such an iconic destination of people or our age. Perhaps your mom was upset by the dunk tank and didn’t want you to see it. If you get the book I site at the end of the post, you’ll see that Mike Royko (remember him, columnist for The Sun Times and then The Chicago Tribune) wrote a column decrying the racist nature of the dunk tank. Riverview shut it down. The African American men went to Royko’s office and complained. “We were makin’ good money for just gettin’ wet,” one said, and those honkies couldn’t get… Read more »

They were upset actually. They went to Mike Ryko’s office at the Sun Times, after he ended their jobs. They were making excellent money, and had no problems calling back out to the throwers, for their attempts to throw at a target that would slide them into the water. Royko wrote had written an article about the game.

A couple of things. I came across your post and clicked immediately since Riverview was a huge treat for us growing up in the 50’s. I don’t believe I ever saw the dunk tank. Maybe my older brothers did, so I’ll ask them. Or maybe I did see it but just figured they were guys doing their job. I really don’t think I would have thought much else. Looking in the rear view mirror I can definitely recognize the segregation that did exist. However honestly, as kids we were clueless. It wasn’t until the 60’s that we really gave it… Read more »

Hi Kathleen. Thanks for reading and for your comment. I do remember the Dunk Tank vividly, because I recall the vein-popping fury the white men had on their bright red faces as they threw the balls to dunk the black guys and the vicious names they called the black men. The N word was in heavy usage along with some other prize names I can’t repeat here. (Of course, the job of the Black men in the tank was to incense the White guys as much as possible). As I mention in the article, yes, the Black men made excellent… Read more »

I came across your post while conducting research for a project. I was not born during the time Riverview was popular; however, I was told stories about how racist the inhabitants of Chicago were during that time. It’s interesting how far the lgbtq community have come while racism has now infiltrated that group and is still very alive today. It actually makes me sad for the future.

Hi Lauren, Thanks for reading and commenting (actually, if you read my response to the previous comment from Kathleen, it includes a lot more information about redlining and the era). I don’t think Chicagoans as a whole are more racist than the residents of many other cities (and it’s not THE most segregated, but one of the most). Virtually all cities in the country were redlined, as the FHA would not back any loans to any buildings (rental or sales) if even a single Black person were allowed in. Yes, I agree that the LGBTQ community quite rapidly were given… Read more »

I was a teenager that went to Riverview in 1966. It was fun and scary at the same time. There were a pack of young teenage afro american kids that were out of control. The place closed down shortly thereafter.

Hi Bill, When I had written a longer reply but WordPress ate it, so I’ll keep this one short. First, thanks so much for reading and commenting. I’m sure that was no fun to feel terrorized at Riverview. Whether those boys were in a gang or just a bunch of testosterone-fueled teens (a necessary component of becoming a gang member or running in packs, though there were some girl gangs too), it obviously frightened you, as it would anyone. If you read my book, you found that my younger brother was punched in the face on Madison Street by a… Read more »

You are exactly right. If one or two little white kids went to Riverview on their own there was a very big chance that they would get jumped by a group of black kids that were just there for that reason. It’s that way in Chicago now with the liberal whites that keep on voting in the democrats that encourage them to riot, carjack, pistol whip, set property and people on fire. These females with their constant racism BS are a big part of that problem too. Why don’t they just shut up! As for the dunk tanks and the… Read more »

Oh, my God, I used to be so good at that, I could have gone into the major leagues when I was a kid! IT WAS HORRIBLE!!!

Oh, come on! This is our history!

Of course. That’s why I write about it. Sorry if I didn’t reply in a timely manner. I thought I had replied.

That’s okay. I was a little kid when I first saw the racist dunk tank at Riverview. I knew nothing of racism, or even of conflict between the races, but when I saw it for the first time, I believe I was traumatized. Horrible.

Hi again, Matt. I know what you mean. I was totally puzzled by the fury of the white men throwing the balls, and the wit the Black men used to instigate the throwers even more. As a kid, I just thought it was the way of the world. I learned better, thank God! Thank you for commenting.

My question is not exactly related to the Dunk Tank spectators, but curious about the spectators outside Aladdin’s Castle. From the photos, it appears as though it was an entirely enclosed building….??? I saw photos of the spectators gallery in the Rotor ride and I guess that was fun…but what was there to see looking at a closed building…?

Sorry for the delay in replying. I somehow missed your comment (I usually get alerted to new comments in a timely manner, but just got the alert today). My recollection of Aladdin’s Castle was that it was entirely enclosed after you entered. My first time going in was with my father at about age 3. I was totally freaked out by the moving floor, which, at my age, seemed to me “real” and about to dump me into some bad place. My father picked me up (I guess I just accepted that HE wouldn’t be dumped somewhere! Ah faith!) There… Read more »

I worked as a rideman on the Pair-O-Chutes in ’58 and ’59. The Pair-O-Chutes was right next door to Aladdin’s Castle. Yes, the Castle was entirely closed, almost! Its inside was a labyrinth that featured a variety of oddities that distracted and disoriented you as you moved through the building. What the crowds that gathered on the midway, in front of the Castle, were looking at was a staircase that ran outside the building, from a room on the ground level, up to a small porch leading back indoors to another room on a higher level. To get to the… Read more »

Hi John,

What fascinating memories you’ve shared here. It’s always great to hear from an insider. I was petrified as a three-year-old of Aladdin’s Castle, and my dad had to carry me through. I didn’t understand at that young age that the floor seeming to buckle was an illusion.

I’m not surprised at the employee who blew the blast up girls’ skirts. So many guys just like to have “fiendish” fun. I’m sure they had a lot of laughs. The girls, not so much. Thanks for reading and commenting.

I was born in 1953 Cook County Hospital, raised in Chicago, Englewood neighborhood. When I look back at the times I was taken to Riverview. But this site made me realize how KKK minded that freaking park really was. My God it was just incredible how what was there, was allowed, yet again I remember it was never suppose to be a place we should be in.

Thank you for reading and for your comment, Dyanna. Sorry for the long delay in replying. Even as a little white girl, I thought the dunk tank was mean, but the park “normalized” this behavior. I can imagine how intimidating and racist this park must have felt to African Americans.

Linda, nicely done. I was telling some younger colleagues about the “game” at Riverview and it was helpful to read your article and the comments of readers. My memories of Riverview were all 50’s and pleasant. It was an exciting place for grade school kids and we were actually allowed to go there by ourselves on the CTA. (Today our parents would be charged with child abuse!) As a youngster I didn’t understand the racism inherent in the “game.” I just remember the humor and audacity of the dunkees. But then the 60s came and we grew up and quickly… Read more »

Hi there, Thanks so much for reading and your comment. I agree that we didn’t understand what was really going on with so much implicit and even explicit racism in our society. Riverview, for sure, was a magical place in our childhood. It was always a highlight to go there, a special place, easily accessible (for us white folks). I also recognize now the life of the carnies who worked the rides. As a kid, they were just adults to me. I realize that most were pretty much on the margins of society, poorly educated and paid, and itinerant or… Read more »

To Dyanna, Linda & M. Plunkett, about racism at Riverview – and Chicago in the ’50s, I need to set the record a little straighter (at least from my point of view). First of all, I never knew any Chicagoan who was not a racist in those days. However, there was little, readily observable sign of it because on the north side, there were no black people; the two races never mingled. As a consequence, white folks, although they doubtless used the “N” word, didn’t give black people much thought, They weren’t preoccupied with hatred or fear about them invading… Read more »

Hi Frank, Certainly many people (maybe most, by today’s standards) in Chicago were racist.Most I knew on the West Side were, but many were not. Many participated in the struggle for Civil Rights. One of my Tilton school co-graduates invited the black kids in the class to his graduation party, and he danced with one of the girls, virtually unheard of. It left a lasting impression on me, at a time when Sammy Davis Jr. and his white Swedish wife were excoriated for their biracial marriage, death threats, losing contracts, and all. I don’t believe my post implies that all… Read more »

Hello, I grew up in the Lincoln Park area. I was taught that there was good and bad in all types of people. Nobody was forced to work at the park and the pay was real good.

Thanks for commenting, Karen.I totally agree with you! I never got the impression anyone was forced to work at Riverview. The Black guys in the dunk tank did get paid well. They were angry with Mike Royko, a famous Chicago newspaper columnist, who called out the dunk tank as racist. The concession was closed down. Not long afterward, Riverview itself was closed down. I wrote about this in the post.

Let’s not forget misogyny. Waiting in the line for the fun house were hidden air vents. A forceful gust of air could be blasted up the vent and make a woman’s skirt fly way up. This happened often to my mother when we went and I still remember my very modest mother’s outrage and humiliation when this occurred. She tried to spot the places and keep her hands holding down the wide circular skirts women wore then (pants were not worn much by women). Pretty disgusting in retrospect.

Hi, Linda — I just now stumbled across this article while reading a Wikipedia article about Riverview. I was born and raised in Chicago, and I have fond memories of many, MANY outings to Riverview. When my siblings and I were very young, we had a babysitter, an elderly woman whom we thought was about 150 (LOL!) but was probably “only” about 65 or so – and VERY energetic and fun-loving. She would take us to Riverview a couple times every summer, and we had to spend what seemed like an ETERNITY on THREE CTA streetcars (this was before buses… Read more »

Many things left out in your article such as in the 60’s there was always at least one white or non African in the booths. Also, that the racist remarks flew BOTH ways & also the black men were not happy with losing jobs to white men in the booths because they were paid a commission & were making a lot of money from inciting throwers….still not a good attraction looking back, but the article was totally based from a racist slant

Thanks for reading and commenting. Sorry, but I don’t have the same memories you have. I never recall seeing a white man in the dunk tank, certainly not “at least one.” The point was to fire up racist comments from the white crowd; the blacks’ replies were, of course, meant to incense the white men so they’d buy more tickets, so they returned as good as they got. The point of the concession was to stir up racial animosity. Yes, the Blacks in the dunk tank made good money, and complained to columnist Mike Royko, as I reported, because of… Read more »

I was born in 60 therefore only visited Riverview once as I recall. My favorite place was Santa’s Village. Glad I didn’t endure the racists taunts of grown men hurling epithets at each other. I am interested in reading your book about Redlining. We would have been considered middle class mom was a school teacher and dad was a Veteran and a CTA Bus driver. That didn’t prevent them from racial discrimination in mortgage lending. Universal Builders didn’t give loans to Black families. So they had a “Contract” on our new home at 9747 S Parnell. Don’t believe they got… Read more »

Thanks for your comment. It’s just terrible that your family, like so many African American families, were denied home loans. It’s a stain on our country. I’m glad to hear they finally got a mortgage, but sorry about the 10 years of payments lost. What a rip-off !

I was born and raise in Maywood, graduating from Proviso High in 1954. Going to Riverview was a yearly event and such a fun time. I was completely oblivious of racism in those years. There was a black neighborhood in Maywood but I remember the people who lived there to be friendly altho we didn’t engage socially. There were several black teens in my high school class. I don’t remember any conflicts at all. I will say that my mother was somewhat racist but not only against blacks but also catholics and jews. Even so, I did not share her… Read more »

Hi Donna, Thanks so much for reading and commenting. My parents were pretty racist too (then we’d have said “prejudiced”) but after they actually came to know their Black neighbors, they were much more accepting. Not necessarily lost every last bit of prejudice, but certainly could see their stereotypes weren’t on target. I have wonderful memories of my CHicago childhood too. My best friend, Barb (to whom I devote an entire chapter in my book), and I still take and agree, we had an idyllic childhood. We didn’t recognize the terribly racist things going on around us. And I agree,… Read more »

I visited Riverview Park as a child in the 1950s and 60s and had no idea what this Dunk Tank was about. I actually thought I was in a safe us

I learned to deeply respect Royko. He was an honest and fair man

Thanks for reading and commenting, Jen. Royko was smart and a clever writer. I was unaware of the true nature of the dunk tank as well. It just seemed rather mean to me. Take care.

Linda

My Article:

“Removal of the “African Dip” dunk tank game from Riverview Amusement Park in Chicago, Illinois.”

Thanks for the link to your article on the Dunk Tank. I’d say we agree on the fundamentals. The Dip was a concession whose time was up. As you say re “historicism,” in the context of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, this dunking game was no longer tenable. Not allowing Blacks and whites to change in the same room? A concept ready to go. I think in terms of historicism, it’s all fine and dandy for whites to say, “Well, that’s just how it was back then,” but the sting of racism, prejudice, and being locked out of… Read more »

Greetings to all in thissite. I grew up in Austin neighborhood, born 1942. My mother and father, maternal Grandpa and my brother and I lived in a one bedroom apartment with Gramps and I in one bed and my brother in another and parents sleeping in the living room in an “In-A-Door: hide-a-bed that foldd down from the wall. RiverView Park was like Heaven to us when we visited for a day’s vacation from life in the early 1950’s. Grandpa loved to try a win a pack of cigarettes from the monkey car races; Aladdin’s Castle and Hades must do’s… Read more »

I am a native Chicagoan and went to Riverview many,many times. I was kind of disgusted at the “Nigger Dunkin’ Game” and never did it. I thought it was awful.

However I did do Aladdin’s Castle, the Bobs, Haunted House, etc. Always enjoyed Riverview (Western and Belmont!)

Thanks for reading and for your comment, Gerald. That was a pretty disgusting concession Yet it made more money for Riverview than any other concession. As I noted in the article, when Royko called it out as racist, and it was shut down, the African American men who participated were furious because they had been making good money – based on the racist notion that whites (anyone could play, but white men were especially virulent in their name calling) could be “talked back to” by the Black men. So, times changed, the men lost their jobs, but it was more… Read more »