In July 1962, a few months after I graduated from grade school and one year before the first black family moved onto our block, The Saturday Evening Post, a venerable magazine of the time, ran an article entitled, “Confessions of a Blockbuster.” I highly recommend it to understand how insidious racist lending policies, exploited by real estate predators, undermined the housing dreams of both black and white families.

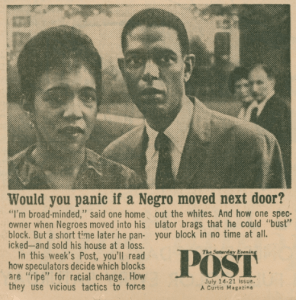

Ad for Saturday Evening Post article, “Confessions of a Blockbuster,” July 14-21, 1962.

A blockbuster was an individual in the real estate business who used racial scare tactics to frighten whites out of neighborhoods mostly by playing on fears of losing the value of their home when blacks moved nearby.

A quote from the first page of the article:

I make my money–quite a lot of it, incidentally three ways: (1) By beating down the prices I pay the white owners by stimulating their fear of what is to come; (2) by selling to the eager Negroes at inflated prices; and (3) by financing these purchases at what amounts to a very high rates of interest.

In my upcoming book, Redlined: A Memoir of Race and Change in 1960’s Chicago, I write about our family’s experience, and the experience of my classmates’ families, with blockbusters. They might call at night, “They’re coming,” meaning blacks were coming to the neighborhood. Sometimes they would leave flyers in the front vestibule, “GET OUT BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE.”

A policeman guards a Negro-owned house that “busted” a May St. block. “For Sale” signs are already up. (from Sat. Evening Post article)

What my family, and probably most whites, didn’t know was that the federal government, including the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), working with the banking sector, had created a system of grading neighborhoods from A (green, signifying best) to D (red, signifying worst). A community was redlined if even one black person moved in. Then banks would refuse to lend for mortgages or home loans. (See my previous post: Race and Change in 1960’s Chicago).

That meant property values for the present white owners would sink, as described in vivid detail in this Saturday Evening Post article. Here are a few more quotes:

You can’t appreciate the psychological effect of such a color-line march unless you have seen it. First, Negro students begin enrolling in neighborhood schools. Then, churches and businesses in the area quit fixing up facilities as they normally might. Parks which have been all white suddenly become all Negro. A homeowner applies to his bank for a home-improvement loan and is turned down. “Too close to the color line,” he is told.

In my book, I go into detail about how changing school boundaries in 1962, the summer after I graduated from 8th grade, had the exact effect on our neighborhood as described in the second sentence of this last quote.

Unable to obtain loans in a redlined area, neither whites nor blacks could borrow against home equity to improve their property. Then, when the community was in disrepair, whites blamed blacks for the deterioration. Within short order, the racial composition of neighborhoods flipped. By 1965 (we still lived on Washington) our community was mostly black. By 1970, the census shows 98% of residents in WGP were African American.

Today, Chicago is still one of the nation’s most segregated cities, and it’s costing us dearly.

Did you already know about blockbusting and redlining before reading this post? Have you had any personal experience, either as a white person or as an African American with this kind of racial change? How did you feel at the time? Do you think understanding the unfair lending policies behind the change make you feel any differently?

Thanks for reading. I eagerly await your comments! Let’s have a dialogue about this.

Great job tracking down historical context. I learn something new every time you post!

Thanks, Candace! Sorry for the delay in responding.

Thanks, Candace. I learned so much new researching this book, I wanted to share.

Yes, I knew. I observed it in South Shore, 79th & Manistee in 1971-72. The white woman who’s family owned the property next door told me and asked me to relay the info to the black owners of the building I rented from.

Such a crazy time. Thank you for your interest!