Next Tuesday, August 28, 2018, will mark the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and the anti-Viet Nam War Protests that once again (after the ML King riots just five months earlier) turned Chicago into a battleground and divided our city and country into camps; the “law and order” crowd (what Nixon called the “Silent Majority” vs. the anti-war protestors. It was the final melee in a year of turmoil that had roiled the nation.

In my book, Redlined, I devote two chapters to 1968, a year that opened with such promise for me, as I was finally able to live on NU’s campus after commuting for four quarters.

It ended with unraveling my belief that our government or authority figures would deliver anything close to real justice. Below is a sneak preview of a portion of those chapters. In the book, prior to what I’m sharing below, I’d already shown my disillusionment, as I wrote in this section on the Viet Nam War:

Our nation’s generals and President Johnson assured us that all was well—we had the enemy on the run and were winning this war. But after the Tet Offensive, well-coordinated North Vietnamese attacks against more than a hundred towns and cities in January of 1968, Americans realized the Communist Viet Cong were far from defeated. We’d been lied to, and a longer war was inevitable.

Two months later, on April 3, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated. In May, about 100 Black students at Northwestern took over the campus Bursar’s office, half a block from my dorm, to demand redress for the marginalization they’d experienced at NU. Northwestern’s president and administration wisely acceded to virtually all of their demands (which were common sense and mild) to avoid the tragic consequences of confrontations between students and police on several other college campuses that year.

Then in June, Bobby Kennedy, whose brother, President John F. Kennedy, had been assassinated in 1963, was himself murdered as he campaigned for the presidency. Below is an excerpt beginning with Bobby’s murder and leading into the Democratic Convention:

I stared at the newspaper photo of Bobby, taken right after the shooting. He lay on the floor, a bright light casting harsh shadows over his face, his arms outspread, as if he were surrendering, his eyes open. A young man cradled Bobby’s head. My gut twisted. He died twenty-six hours later.

Alone in my dorm, in between final exams, I slid down the wall of my room onto the floor, pressed my head against my scrunched-up knees, and sobbed for a fraying, incomprehensible world of brutality and murder. King’s death, riots, takeovers, protests, bombings, war, and now this. Life was the opposite of all my brothers and I had been taught to believe: that we—and all people—were in charge of our lives, our fate. That outlook now seemed like a fantasy.

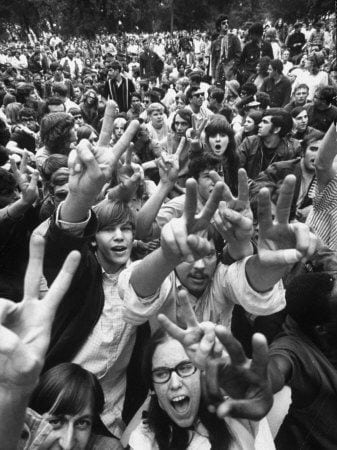

Young protestors at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago

More violence was just two months away. The 1968 Democratic National Convention was scheduled to be held in downtown Chicago. Hippies, Yippies, and protestors were planning huge antiwar demonstrations to disrupt the convention and take advantage of the media spotlight.

I was back at home for summer break, working downtown at First Federal Savings & Loan. When the news hit that Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman threatened to spike Chicago’s water supply with LSD, panic flamed through the city. It sounded wacky to me, but nothing seemed too far-fetched that year.

Why would anyone consider poisoning an entire city? Dad said, “They’re anarchists. They want to destroy everything. They’re just sick people and should be put away.” I had to agree.

Mayor Daley was leaving nothing to chance. I later learned that he had dispatched nearly 12,000 police officers on twelve-hour shifts, ordered 5,649 Illinois National Guardsmen with 5,000 more on alert, and up to 1,000 FBI and military intelligence officers at the ready. The 101st Airborne Division and 6,000 army troops, equipped with bazookas and flamethrowers, were waiting as backup in the suburbs.*

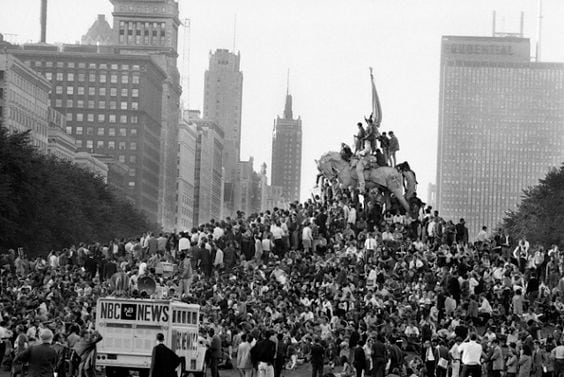

Chicago: Protestors form a human pyramid as they crowd around a Grant Park statue next to Michigan Ave., just blocks from the Hilton, site of the Democratic Convention

“Pigasus” One of the more bizarre antics of the protestors: they nominated this pig, dubbed “Pigasus,” as their candidate for President of the U.S.!

By August 23, thousands of young people settled into Lincoln Park, a few miles north of the convention site on Michigan Avenue. I had zero interest in taking part. The nightly news turned into a kind of bizarre theatre. Mayor Daley was determined to clear out all protestors by eleven o’clock, the park’s official closing time. Ordered to disperse, the crowd defied baton-wielding police officers, who shot tear gas into the throngs. The protestors took to the streets, chanting antiwar slogans and marching south toward the convention center.

With this backdrop, Grandma Gartz called Mom to chide her and Dad for not keeping the fence at the six-flat properly painted. Grandpa had driven by his former building and said if we didn’t paint it, he’d go there himself to do it.

In her lifelong attempt to mollify her impossible mother-in-law, Mom said to Dad and Billy, “Well, if it will make her happy, why don’t we go and paint the fence?” Dad refused, but Mom found a willing accomplice in Billy. They spent three days painting that fence while mayhem unfolded five miles to the east.

Police beat protestors during the 1968 Democratic Convention

Between August 23 and 28, confrontations escalated between as many as ten thousand protestors and a combination of Chicago Police Officers and Illinois National Guard (about 20,000 uniformed personnel)—and television again brought it all home. Police roughed up reporters, innocent bicyclists, residents in their doorways, and a young man who stripped a flag from its pole. Demonstrators responded by throwing food, rocks, and concrete at the officers, as crowds of young people shouted to the cameras: “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!”

By the time I understood the extent of the vicious response of the police to the protestors, toward neighborhood people, passers-by, reporters doing their jobs, and others, who had been beaten and arrested, my faith in authority was in tatters. A later report, called Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), which investigated the violent clashes during the convention, called the entire event “a police riot.” It didn’t matter. Most Americans were firmly behind the “law and order” stance (even if it meant the cracking the heads of total innocents) and blamed the protestors.

Fifty years later, I look back at that year as a watershed in my life. It forever changed me and so many of my generation to question authority, to be skeptical of anything the government or politicians might tell us (in a few years, Watergate would further erode any belief in our elected officials), to see the tragic results of unrestrained power, against which we have to always, especially today, remain vigilant.

*These facts are from the book, Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention, by Frank Kusch

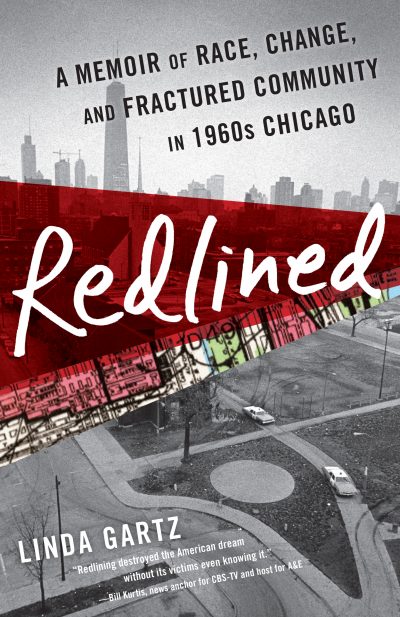

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

ORDER NOW:

Thanks Linda. It’s great to read this personal testimony from the crucible of Chicago 68. What did you think of Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool – did it capture the event accurately? I wrote an audio drama about this period recently, but my young heroine went in a different direction, embracing the ideas of Ayn Rand in her anti-state journey. You can check it out if you like at https://redthreadproductions.org/red-thread-silent-majority/