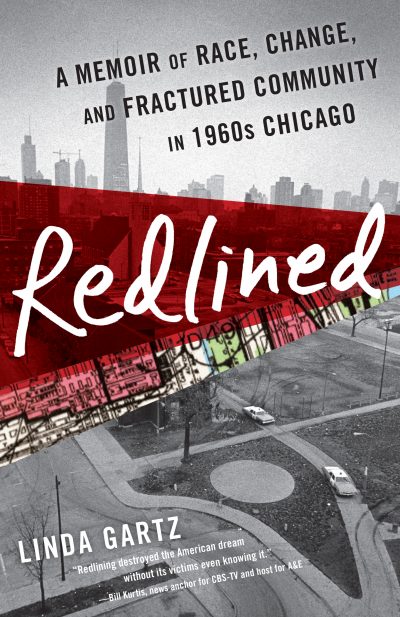

On January 15th, a few days ago, the New York Times ran an article entitled “50 Years Later, It feels Familiar: How America Fractured in 1968.” I was struck by how I’ve used the same word, fractured, in the title of my book: Redlined: A Memoir of Race, Change, and Fractured Community in 1960s Chicago. I’m going to share just a portion of that year as covered in my book.

The NYT article ponders what might have been different if we’d had news alerts vibrating on our phones back then. But we didn’t. Instead we had to absorb the nightly news, packing in all the horrors.

I was attending Northwestern University, but had lived at home my entire freshman year and fall quarter sophomore year to save money. I finally got the chance to move onto campus when a friend in French Lit class said she had lost one of four roommates. I pick up the story in January 1968, winter quarter. Future sneak previews will get into the other fracturing of 1968.

From Chapter 33: Riots Redux

In January 1968, I moved into the “Northwestern Apartments,” where Marge and I shared one of two bedrooms; Joanie and Rikki the other. We all used the common bathroom. I kept quiet when I learned the generous allowances each had. They often skipped breakfast or chose to order pizza for dinner instead of eating the dorm food. With meals already paid for, I never missed a single one.

Marge—zaftig, smooth-skinned, smart, and focused—had beautiful clothes, lovely lingerie, and an open smile. She had brought her record player, which she invited me to use any time, a first gesture of many that made me feel welcome to the group. And what wonderful albums she owned! Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, Bob Dylan, the Beatles—all the ’60s greats, none of which I owned. I played them all over and over…

Girls from other rooms came to ours to chat, gossip, and share their traumas. One hated the food (I thought it was fine); another just “despised Northwestern” and planned to quit. Thrilled to be able to attend NU, I was perplexed by her petty grievances. Some girls were just psychological messes, anxious and sobbing over a project due the next day, about other girls stealing their boyfriends, or fights over money with their horrible parents.

Some talked openly about their sex escapades with this guy or that, sometimes boys in the same fraternity house. With my anti-pre-marital sex upbringing, I was flummoxed. They all seemed like perfectly nice girls, not “whores” as my mother referred to women who slept around.

As January came to a close, I was getting comfortable with dorm life and the widely disparate characters I’d met. I had no way to imagine the upheavals that lay ahead.

***

Nightly news programs beamed the Vietnam War right into America’s homes and college dorms across the nation. War was a vague concept I had studied in history class. I knew Ebner’s death after World War II had permanently scarred Dad and my grandparents, but I had experienced none of it. Now TV gave all Americans an eyewitness view.

Boys, my age, hunkered down in swamps; scared; confessing to television interviewers they didn’t know why they were in Southeast Asia. I saw CBS news reporter, Morly Safer, reporting from a small Vietnamese hamlet, burned to the ground by American troops. Children and elderly women, stunned and blank-eyed, wandered like ghosts among the charred ruins. I felt sick at the images—at the thought of my brothers, friends, or Bill moldering in those swamps, killed, blown apart, or tortured in a POW camp.

Day after day, we watched body bags unloaded at airports; I tried to comprehend the young men my age dead and rotting in black zippered plastic. TV footage of helicopters, the “whop-whop-whop,” a sound track to countless scenes, spraying Agent Orange, defoliating thousands of acres of farmland. We learned only later it had poisoned our own troops.

An American lieutenant carried a wounded So. Vietnamese Ranger to an ambulance in Feb. 1968, during the Tet Offensive. credit: Dang Van Phuoc/A.P

Meanwhile, our nation’s generals and President Lyndon Johnson, assured us that all was well. We had the enemy on the run and were winning this war. But after the Tet Offensive, well-coordinated North Vietnamese attacks against more than a hundred towns and cities in January 1968, Americans realized the Communists were far from defeated. We’d been lied to, and a longer war was inevitable.

The specter of being drafted and sent to Vietnam hung heavy over every young man, including Paul, Bill, and Dietmar. As college students, they all had deferments—for the time being. I watched tens of thousands of young Americans march and demonstrate in anti-war protests across the nation, denouncing the war as immoral. I was not politically astute, and read the conflicting opinions of the “Hawks” and “Doves” unsure what to believe.

But the lies and dissembling, the scenes of innocent children and farmers killed, their livelihoods destroyed, drove me into the anti-war camp.The mood of NU’s campus had flipped since I’d enrolled. As a freshman in fall 1966, Greek life was all-powerful. The mostly wealthy population of coeds had dressed for class in expensive skirts and sweaters, even tying color-coordinated bows into their hair.

By 1968, dressing up was becoming passé, replaced by a uniform of jeans and t-shirts, better suited to the spreading mood of defiance. Students focused on the War and The Civil Rights Movement instead of sororities and fraternities, a transition still in flux when I pledged. We questioned everything. In spring of 1968, women protested the paternalistic curfews governing female students. Northwestern men could come and go from student housing as they pleased, but women had to be in their rooms by eleven p.m. weekdays and midnight on weekends. Just a couple months after I moved onto campus, NU introduced more gender-equal hours but only with parent approval for the females.

Mom felt the more lenient dorm rules were an “invitation to temptation.” Since my childhood Mom had lectured me against premarital sex, adding admonitions like, “Why buy the cow when the milk is free?” I know her intention was good—to protect me from an unwanted pregnancy. Abortion was illegal, and use of birth control pills (FDA-approved in 1961) was severely restricted. As recently as 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared the state’s “Crimes against chastity” law unconstitutional, it had been a felony in Massachusetts to provide birth control to unmarried people.

Dad believed in as much freedom as possible for his kids, so I had to persuade only my mother to sign off on the unrestricted hours, which she finally did. But dorm rules turned out to be the least of my parents’ problems that spring.

…to be continued. The Assassination of Martin Luther King, and the fury that followed, forever changed Chicago’s West Side.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

I remember those days very well

Me too. Thanks for the comment.

Well, then, Bill, we must be about the same age – or not too far apart. Unforgettable times. Thanks for posting and sorry for the long delay in receiving a reply.

I was a Sophomore at Depaul in 1968; I lived through you same experiences. It was not a good time for America.

Wow! Am I ever late in replying to you. So we were both sophomores at the same time. No, it was NOT a good time in America – and a very disturbing time to enter adulthood.

Correction: “your”

Hi Jack,

No, it was a very disturbing time. Here we are, 50 years later, and so many problems are still with us. Every time I see those boys in Vietnam, though, my blood boils. Lies from the government, cover-ups to win elections – and let our boys die. Thanks for commenting and I’m sorry for the long delay in replying.