Alcoholism. Psychosis. Strange men renting our bedrooms: these were just some of the stressors my mother had to handle alone when my Dad traveled hundreds of miles away for up to seven weeks every winter. This Women’s History Month, I honor her grit, even if I question the choices of both my parents!

In Redlined, the following scenes, leading up to my dad’s long trip in January 1950, are presented in a mere couple of summary paragraphs. To keep the book moving forward, I cut most of the detail. But by reading these events in their entirety, we get a cinematic view of my parent’s lives in their attempts to garner some extra income with a rooming house on Chicago’s West Side.

A little background: Grandma K (Koroschetz) is my mother’s mother. She’d had two psychotic meltdowns: in 1946 and about in February 1949, about a year prior to this scene. Psychiatrists had recommended she be institutionalized, but my mother insisted she live with us. Grandma K’s “bedroom” was an alcove of the dining room, across which Dad had rigged up rope with a sheet to pull across. My brother, Paul, also slept in the dining room, as all the bedrooms were rented out.

From the Cutting Room Floor: “Best-laid Plans”

My parents and Grandma K, who moved in with Mom & Dad when widowed, 10 months after my parents were married. 8 months later, she rented her own apt. but eventually lived permanently with our family.

On New Year’s Day, Grandma K shambled into the kitchen, her untied flannel robe hanging loosely over her nightgown. “Happy New Year, Mama,” Mom said as she was cleaning up after the previous night’s intimate New Year’s Eve party. Grandma didn’t respond.

Glasses etched with my parents’ initials, a treasured wedding gift, sat smudged and lipstick-stained on the table.

When Grandma K brushed against one, it teetered, then fell to the floor. Seven years of memory shattered, lying in pieces.

“Oh dear!” was all Mom mustered, knowing better than to scold her mother. Striding to the pantry for a dustpan and broom to sweep up the shards, Mom felt the electricity of her mother’s madness crackling nearby.

“You put that glass there on purpose!” Grandma K screamed into Mom’s bent-over face. “Just so you could blame me for breaking it!” In Grandma’s warped mind, a sinister motive lurked behind every mishap, no matter how minor.

“That’s silly, Mama,” Mom said, making no eye contact, brushing up the last slivers. “It was just an accident.”

Grandma’s voice rose, “Don’t tell me it’s an accident!” Her face shook with rage. “Why are you always causing trouble?” Scrubbing calcimine from the bedroom walls, Dad heard the commotion and hurried into the kitchen to see Grandma K raising her fist to strike Mom. He shouldered between them, grasping his mother-in-law by her arms.

“Hold it. Now stop that. We don’t hit in this family.” Dad had amazing self-control, an uncanny ability to hide his emotions, learned from a lifetime of battles for control with his own mother. He had to stay calm, not only to prevent Grandma’s madness from escalating, but to keep Mom’s anxiety in check.

View of entire 4222 flat, kitchen to living room. Mom stands outside her bedroom. Grandma K slept in the next room, in an alcove on right. I have no idea what Mom finds so hilarious.

As the fire slowly leached from Grandma’s eyes, Dad maneuvered her into the dining room. “Lie down and get some rest,” he said. She fell heavily onto her bed, and Dad pulled the sheet across the clothesline.

Coping with Grandma K was just one of many stressors that plagued my parents in the early 1950s. It may have “seemed perfectly normal” to Mom when they moved in with the other three tenants, but she hadn’t realized the chaos that would ensue. After all, my parents hadn’t vetted these people. They came with the place.

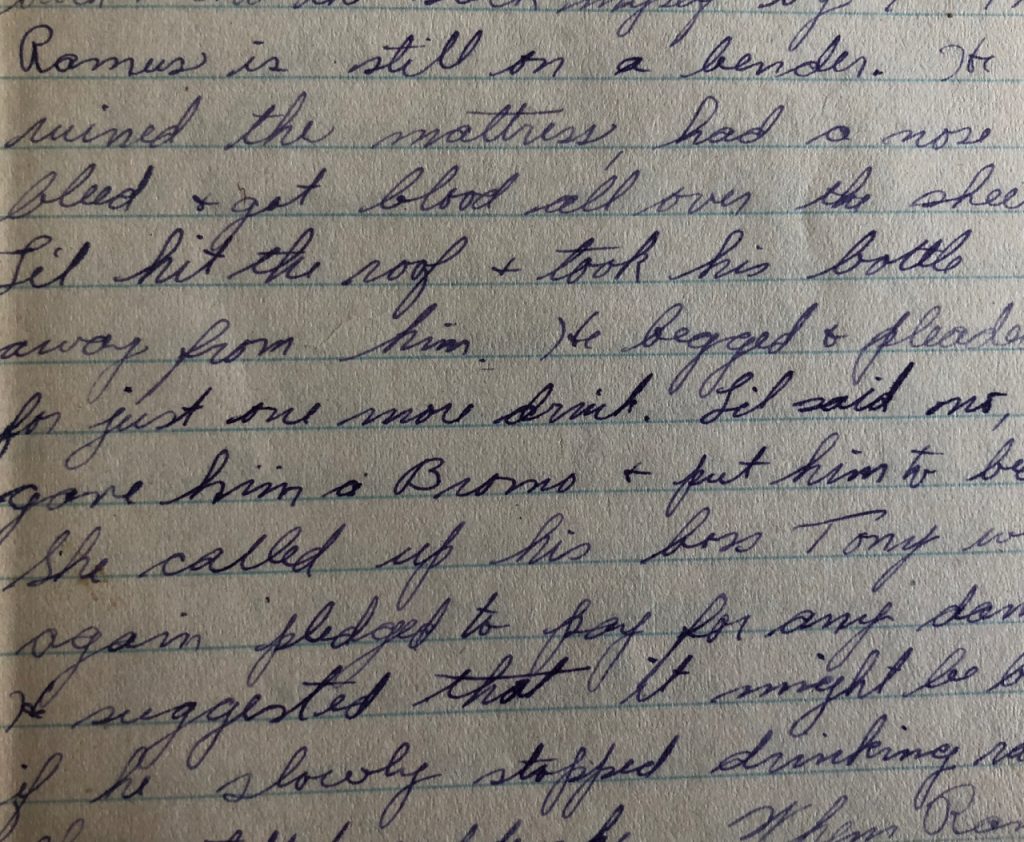

Dad’s diary entry (he misspells Ramis) on one of the events in this post. “Ramus [sic] is still on a bender,” he writes, meaning: drunk.

Two of the roomers were alcoholics. One, a Mr. John Ramis, was “on a bender” for three days. Mom had already taken two liquor bottles away from him after he had spilled whiskey on the dresser my parents furnished for his room, causing twenty-five dollars damage. The rent was only nine dollars a week, so the repairs represented almost three weeks of income.

Now, just before Dad was to leave town, Ramis was groaning in his bedroom. Mom and Dad knocked, then entered to find him lolling on his bed in a drunken stupor. The sheets and mattress were soaked with blood from his nosebleed.

Furious, Mom yelled, “Mr. Ramis! We can’t tolerate this kind of behavior! I’m taking this too!” she said, grabbing yet another whiskey bottle and stomping to the kitchen.

“Oh, please, please. Let me have just one more drink,” he begged.

“Absolutely not!” Mom said. She had come back to his room from the kitchen with a fizzing Bromo Selzer. “Here, drink this.”

Dad walked Ramis to the bathroom to clean him up, while Mom changed the sheets in his bedroom. Then they helped him into bed.

Mom called Ramis’s friend and boss. “Tony? This is Lillian Gartz. Listen, Mr. Ramis is drunk again. You have to get him out of here. I have two little children in the house. Take him home and sober him up. Then he can come back.”

“I’ll come to get ‘im,” Tony said, “and I’ll pay for that ruined dresser too. You know, John has never been the same since the war.”

My parents had a soft spot that was more like a blind spot. Instead of kicking Ramis out for his ruinous behavior, they defaulted on the side of kindness, always willing to give someone a second chance.

Such was the situation at home as Dad headed out to Lorain, Ohio, for a week. While he was gone, Mom wrote to him that one tenant was three weeks behind in rent, then continued with a rundown of her workaholic endeavors. “I pushed myself and scrubbed the doors, window frame and upper molding in [one vacant bedroom] and steel-wooled the floor, then washed it and tonight plan to varnish.

“Mama is doing a very fine job of keeping house, and washed the supper dishes too, so that helps a lot.” Mom began passing on more and more of boring “housewife” chores to her mother, giving herself time to manage everything else.

My parents’ laudable goal had been to create a lovely family home and build a nest egg of savings with the two-flat’s rent adding to Dad’s income. But his traveling job up-ended this carefully-thought-out equation, leaving Mom to manage alone with two little children and out-of-control-tenant behavior. It was inevitable that a co-dependency would evolve between my mother and Grandma K from which Dad was excluded.

After the Ohio trip, Dad was home just one week, devoting every evening after supper, often until 1 a.m., to refurbishing the house. He was determined to complete as many projects as possible before leaving again.

Clustered around the front door, we waited on January twenty-second for Dad’s NBFU colleague to pick him up for the long drive to Austin, Texas. I was ten months old and Paul was three–too young to comprehend how long a twenty-one-day-absence would be. But Mom would feel it acutely. Dad’s co-worker pulled his Studebaker up to the curb. Hugs and kisses and “I’ll miss you. I love you,” all around.

Dad pushed open the outer glass door and walked down the concrete steps onto the cold, gray Chicago street. Once in the car, Dad waved back at us, smiling, but a hollow must have settled under his ribs.

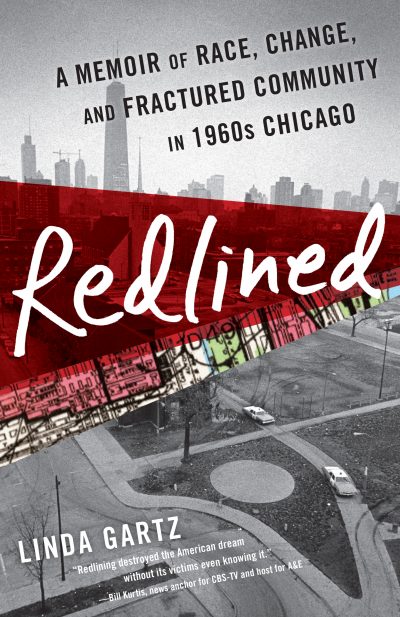

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.