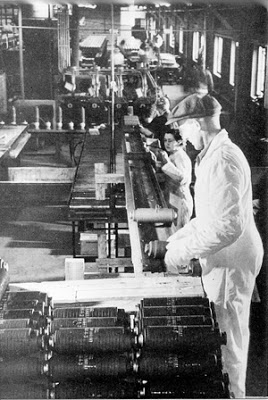

Munitions are processed at Kingsbury Ordnance Plant during World War II. Photo

courtesy of LaPorte County Historical Society Museum

In last week’s post, “War and Bigotry” I shared a letter from Fred Gartz (my dad) to his mother detailing his summary firing from the Kingsbury Ordinance Plant. No one would tell him why he was fired, or they said cryptic things like, “You know what’s wrong,” or told blatant lies about the quality of his work. We pick up as Fred continues to be shuffled from one office to another, each person telling him to see someone else and making such comments as, “I don’t care to discuss it,” and “I know nothing.”

Fred finally tracked down the assistant personnel director, Mr. Hibbert. “He, too, wouldn’t tell me anything, but he promised that he would have my case re-investigated and I should come back in ten days.” [TEN DAYS!… to cool his heels with no money coming in and a sick feeling in his stomach.]

Fred wrote, “All I wanted was a chance for someone to stand up and accuse me openly. Then I can defend myself and break up their false accusations.”

He was caught in a Kafka-esque world of lies, double-talk, and run-around, with no idea why he was being fired from a job for which he had given up another, moved to Indiana, and now faced the likelihood of a black mark on his employment history. “I had practically no appetite, and spent my days reading the newspaper from cover-to-cover.”

He doggedly pursued anyone who could enlighten him: he met with the head of his lab who said he’d heard Fred was reported for leaving his post and disappearing for an hour, a lie. He told Fred to again see Mr. Barab, who had dismissed him in the first place. Unable to find Barab in his office, Fred went to Barab’s home to plead his case, again asking to be accused directly so he could defend himself. Barab told him to see Hibbert, the assistant personnel director, who, perhaps at Barab’s urging, was willing to see him sooner than ten days.

He went to see Hibbert the next day and was grilled in a manner reminiscent of the kinds interrogations usually associated with totalitarian regimes, bizarre questions that seem intended to find some obscure answer to project blame. Fred continues the letter to his mother:

“[When] I saw Hibbert the next day I had to answer about 1,000 questions. Complete history of myself and of Will and Ebner (his brothers), you and Pop. When you came here! Why? What relatives we had back in the old country. How often we get word from them and how often we write. What are my feelings in this war and what are yours? My entire life was chopped into fine pieces and each examined. What are my hobbies. How do I spend my time. Where I eat, what I eat, and why?”

[Who could possibly explain why they eat something! Because I like it? I’m hungry?]

“They knew my every move since I came there and every thing I told them they already knew.” Apparently he’d already been investigated. “I spoke the truth in every instance because there was nothing I had to hide.”

Hibbert asked if Fred could prove he was born in the United States (Note: Fred had to produce his birth certificate to get the job!)

“Yes,” Fred, surprised. “Why?”

“Why do you speak with a strong German accent?”

“This surprised me. Then I became conscious that I was nervous, but my mind was clear, and I chose my words to be the most effective. [It resulted] in my speaking in short, quick phrases, pronouncing every vowel, every consonant. I told him I can speak just as good English as he could.”

Hibbert wanted to know where Fred learned to write and why he crossed his sevens and made an “F” like a German “F!” Fred responded, “I told him it was plain habit and he and the country had nothing to worry about where our loyalty was concerned.

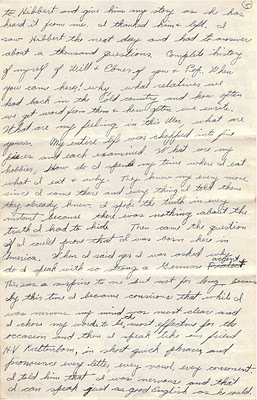

Will Gartz, Dad’s older brother, serving in the Civil Air Patrol. Photo taken 1943-44 Harlem Airport

“Hibbert asked if I cared if the whole family were investigated by the F.B.I. I said I didn’t care, and told him that the FBI has our records because of Will’s [older brother] membership in the Civil Air Patrol.”

Here one brother was serving the country, already vetted by the FBI, and another brother was soon to be drafted, and this assistant personnel manager was questioning the whole family’s loyalty, primarily because Fred “crosses his sevens,” and they are suspicious of his “Germanic” heritage, although the family was not from Germany.)

Hibbert ended the interrogation by saying he was satisfied and that Fred should come see him Tuesday. Fred believed he had saved his job.

He ended the letter to his mother by writing, “I wanted so badly to come home for Mother’s Day, but the honor of the family name comes first. If I was ever homesick and wanted someone to talk to and listen [to me], it was this last week. I was mentally sick and a wreck. My only consolation was the Book of Psalms and therein was my answer.”

A few of the Psalms he mentioned include these, for which I’ve included a key line. Click on and read if you wish:

Psalm 4 “…thou hast enlarged me when I was in distress…”

Psalm 7 (A prayer for vindication) “…save me from all them that persecute me, and deliver me…”

Psalm 27 “…When the wicked advance against me to slander me, it is my enemies and my foes who will stumble and fall…”

Dad was not super religious, but he had been a regular Lutheran church-attendee since childhood, sang in the choir, and apparently was familiar enough with the Bible to take consolation from reading several Psalms. ‘”It gave me a complete feeling of confidence and self-expression…and gave me the assurance to stand up for my just rights and made me able to take all those questions and drilling unafraid.”

After all that, Fred felt confident he had settled any further questions about his loyalty and fitness for his employment, for which he had given up so much. Next week we’ll learn the conclusion.

Comments always welcome. Please post your comment below.

Gadfry! Fear drives away reason once again. Due process pilloried by prejudice, an all to familiar occurrence in the USA. What a cliff-hanger you have masterfully written again! I am not too optimistic about the outcome, though. Katy

He would empathize with the prejudices shown toward Muslims in many communities. History repeats itself over and over.

It’s been interesting to learn of this anti-German paranoia during WWII. I wonder whether there was also anti-Italian prejudice and whether any Europeans were interned.

Fear is certainly an enemy of reason, and this result had a lasting effect on my dad, and yes, Miriam, Dad would have found today’s knee-jerk anti-Muslim prejudices disturbing. And Adrienne, check out the link in the previous post to internment camps for Germans and Italians in the U.S. Thanks to all for your thoughtful words.

It’s hard to believe that you would be suspect simply because of your last name. In my husband’s family the Italian branch changed their last name so that “they would not be associated with the wrong part of Italy.” I still haven’t quite figured out what they meant by that but that’s the family tale.

It’s incredible to read everything he had to go through! I so want the resolution to go well for him!

I have a feeling this isn’t going to end well, either. I’ve been reading so many books about the plight of the Jews, Palestinians, etc. and all of the stories are so similar in the end. I agree with Marian’s comment — these stories apply to so many communities.

I found this post looking for documentation of an old story from the area that, I suspect, could have been related to this. A couple that lived in the area (maybe worked at the munitions plant too– i know that is what they were spying on but dont remember if they worked there or not) were found to be german spies with a hidden radio built in to a table or bench or something in their house within a few miles of 30 and 35. My family were of german heritage in that area (came in the late 1800s, but… Read more »

There is always paranoia during war. We can understand this in the broad view, but when it affects on personally, like losing a job or being shipped to a detention camp, like the Japanese-Americans were at the time, it’s galling. Thanks for your perspective.