At West End and Keeler Avenues in Chicago’s West Garfield Park, an elliptical blue-green dome rises above the surrounding bungalows and two-flats. It is the pinnacle of Bethel Church, a symbol of community and an anchor to this neighborhood for more than 135 years.

Bethel Evangelical Lutheran Church, West End and Keeler

For more than half of the last century, it was the home church for three generations of my family. Beginning in the mid-1960s, after the area was crippled by riots, poverty, drugs and despair, Bethel was determined to re-create community out of chaos, and it became the spiritual base and guiding light for one of the nation’s most successful community development organizations: Bethel New Life.

Bethel New Life has brought jobs, housing, health care and hope to this community, thanks to the now-retired group’s founder and visionary, Mary Nelson. I interviewed her when she stepped down from the position of president in 2004. This post reprints that interview as we remember the devastation that came to the West Side after the riots in the wake of King’s assassination.

Looking back on the organization’s accomplishments, Nelson said Bethel Church has been at the core of rebuilding the neighborhood. “It’s the people,” she said. “Their prayers shore us up. There’s a sense of partnership and the role of faith in community-building.”

Mary Nelson, founder and first president, Bethel New Life

Bethel Church has a history of creating community on the West Side from its beginning. Bethel Evangelical Lutheran Church was founded in 1891. In the early days, services were in German to meet the needs of residents like my grandparents, ethnic Germans who began attending Bethel in 1910 after emigrating from Romania.

By the early ’30s, Bethel provided a lively gathering place for young people, including my dad, Fred, who participated in one of three large choirs, summer picnics, fall horseback riding and winter sleigh rides.

My parents married at Bethel in 1942, and seven years later, they purchased their first home around the corner from the church on Washington Boulevard, where I grew up.

West Garfield Park was a vibrant neighborhood in the ’50s. On and around Madison Street was a shopper’s paradise: specialty stores, movie theaters, a branch library, and the kids’ favorite, the Off-the- Street-Club, where we painted ceramics, wove potholders and made papier-mache puppets.

But we had no idea our lives were built along a fault line of social unrest that would shortly lay waste to this area. Between 1960 and 1965, 30,000 whites left West Garfield Park, and 60,000 blacks moved in.

The effect on my church was dramatic. By 1965, there were sometimes only three members at choir practice, and on Sundays, we sang in a church virtually devoid of worshipers. In March of that year, our retiring pastor, Oscar Kaitschuck, sobbed as his last benediction echoed in the emptiness.

The new pastor, David Nelson, arrived five months later in the August heat with his sister, Mary. “I only came to help David get settled in. I thought of it as temporary,” recalled Mary Nelson. Within three days of their arrival, the first riots exploded along Madison Street when a firetruck raced out of the Pulaski- Wilcox station with no one manning the ladder. It swung out of control on a turn, killing a young black woman. Rioters burned buildings, looted stores and threw bricks through passing car windows.

In 1966, we moved 5 miles north, but my parents didn’t sell their buildings on Washington. Instead, my father returned to his old neighborhood every Saturday to maintain them as rental properties.

After Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968, a far more devastating riot ripped apart West Garfield Park, destroying the Madison Street business district. Manufacturing jobs disappeared from the area. Banks closed. Businesses and hundreds of homes were burned out or shuttered.

With vacant lots and hollowed-out buildings on every block, the area drew comparisons to Berlin after World War II. But there was no Marshall Plan.

“By 1979, we knew we had to do something about housing, or there wouldn’t be a community to be church of,” Nelson said.

In 1979, the Nelsons turned to Bethel Church’s members to contribute $10 per week to raise the $5,000 needed to purchase and rehab an abandoned three-flat at 367 N. Karlov Ave. With that bold move, Bethel New Life was born.

Mary Nelson became renowned for her creative approaches to providing low-income housing. In 1983, my parents were in their late 60s when Bethel New Life offered them a way to sell their buildings, which were becoming increasingly difficult to maintain. The organization agreed to pay half the appraised value of two of their properties, over time. The other half was treated as a tax-deductible contribution to the organization.

For neighborhood residents wanting to own a home, Bethel used the self-help model: Potential buyers could invest sweat equity to renovate or rebuild housing in lieu of a down payment. One building at a time, Bethel began reclaiming the neighborhood.

“The most important thing about the church,” Nelson said, “is it gives us a chance to be God’s servants in the community. I hope that continues as the promise.”

Now, fourteen years after Mary partially retired, she still lives on Chicago’s West Side, in the community which was devastated after the riots following King’s death and where she has worked for more than fifty years to bring housing and justice.

Listen to her interviewed by Tony Sarabia on this morning’s WBEZ, The Morning Shift, broadcast live from “Out of the Past Records,” at 4407 Madison Street, about two blocks from where I grew up. Morning Shift Goes to Chicago’s West Side.

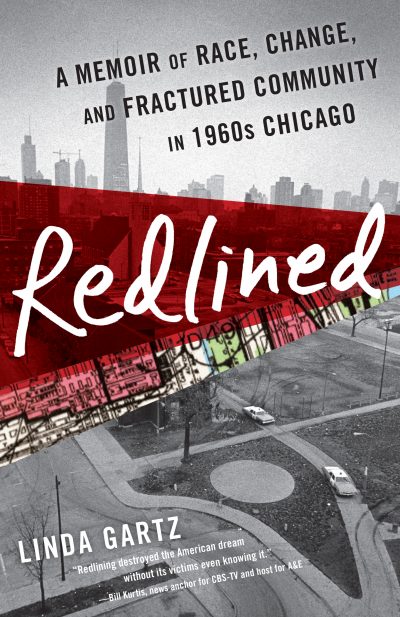

Mary and Bethel Evangelical Lutheran Church are an integral part of my book, Redlined.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

Great story.

Thanks for reading! Glad you liked it.

Linda

Hi Venoria,

So glad you enjoyed it! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Linda

I was not a member but my brother Wilbur Moore. Later He Married to Debra who also a member. My Mother Jean Moore, Mrs. Biggs was a door keeper got many years. My Grand Mother Margaret Jackson we had her Service at BetheI. I could go on an on. Bethel new life has been the pillow of those has gone on an the present.

Hi Linda

So wonderful to hear of your connection to Bethel! My family had a presence in Bethel Church starting in the 1920s. My dad and uncle were confirmed there in 1927 and 1926 respectively. My parents married at Bethel in 1942. My older brother and I were both confirmed (and all three kids baptized) there. I taught Sunday School and sang in the jr. and sr. choirs. I have treasured memories of Bethel.

My father was a deacon, I became a girl scout, Pastor Nelson was great pastor, he was Swedish just like my husband, he married us coming out of retirement 22 years ago.