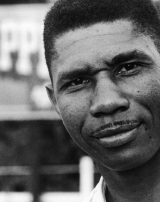

“Thirty-seven-year-old Medgar Evers, Mississippi’s NAACP field secretary, was shot in the back with a high-powered rifle as he walked from his car to his home on June 12, 1963. He died an hour later. Again, mass black protests, followed by mass arrests were broadcast on TV around the world. I later learned that neighbors had heard Evers’s children screaming, ‘Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!’[1] I thought of my daddy. What would I do without my daddy?

Medgar Evers

This recounting of Medgar Evers’s murder (barely three weeks before his July 2 birthday) is an excerpt from my upcoming book, Redlined: A Memoir of Race and Change in 1960’s Chicago. The quote from Evers’s children comes from the reporting of Claude Sitton (see source at end of post). It describes one of so many horrid racist events that took place in 1963, when racist attacks were daily news.

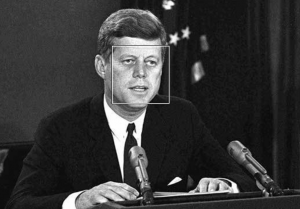

President John F. Kennedy delivering to the nation his call for racial tolerance 6/11/1963

Just the night before, President John F. Kennedy had addressed the nation, calling for racial tolerance. He had every reason to do so. That very day, June 11th, Kennedy had to call in federal troops to force Alabama governor, and avowed segregationist, George Wallace, to stand aside from the entry to the University of Alabama and allow black students to enter.

“Segregation, now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever!” Wallace had declared in his inauguration speech that year.

In a vicious rejoinder, Evers was murdered the day after Kennedy’s appeal for racial fairness by Byron De La Beckwith, a Ku Klux Klan member and white supremacist. De La Beckwith was found “not guilty” by what was later to-be-determined to be an illegally chosen jury. For thirty-one years he lived as a free man, until he was finally convicted of the murder in 1994, with essentially the same evidence.

In a vicious rejoinder, Evers was murdered the day after Kennedy’s appeal for racial fairness by Byron De La Beckwith, a Ku Klux Klan member and white supremacist. De La Beckwith was found “not guilty” by what was later to-be-determined to be an illegally chosen jury. For thirty-one years he lived as a free man, until he was finally convicted of the murder in 1994, with essentially the same evidence.

So why am I writing about this now? Because the national focus on race in 1963 and the Civil Rights Movement’s determination to overcome the racist Jim Crow laws in the South, came at a time when my family’s own ability to be racially open was tested. Less than two weeks after Medgar Evers was murdered, with racial violence dominating the news, the first black family moved onto our block in Chicago’s West Garfield Park community.

Whites in my neighborhood, including my family, weren’t thinking of fairness. First, people worried about their property values.

It was an article of faith among many people in Chicago and other big cities that the arrival of colored people in an all-white neighborhood automatically lowered property values.…The fears were not unfounded, but often not for the reason white residents were led to believe.

—The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson’s book on the Great Migration

That’s when the Blockbusters got busy. (See: “Would you panic if a Negro moved next door?”) Our family, and most white families in the neighborhood, didn’t know any black people. How would they behave? Would the neighborhood become a slum, like whites who rioted against blacks entering their communities predicted?

We were worried, but my parents decided to wait and see. Other whites didn’t wait. By August, two months later, just as Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic Dream Speech at The March in Washington ( See my post on King’s “Dream” speech,), four houses on our block had been sold to blacks. The white diaspora had begun.

[1] Sitton, Claude « N.A.A.C.P. Leader Slain in Jackson : Protests Mount « from Reporting Civil Rights Part One : American Journalism 1941-1963, Penguin Putnam Inc. 2003

[2] Wilkerson, Isabel; The Warmth of Other Suns; pg 376

As always, looking forward to reading more…

As always, Marilyn, though this is a very late reply, I’m always so glad to hear from you!