On December 12, 1989, I arrived at my parents’ home in the Old Irving Park neighborhood of Chicago. My mom, Lillian, wanted to attend practice (she was a cellist) with the Wright Junior College Orchestra and asked me to stay with Dad while she was away from home for a couple of hours.

Stroke

After a devastating stroke in September 1984, Dad’s left brain had “basically been wiped out,” according to the neurologist who showed us his brain scan.

He had been instantly transformed from a fun-loving, joke-telling, outgoing, gregarious, garrulous raconteur into an invalid, unable to speak, read, or write (language ability is housed in the left side of the brain), paralyzed on his right side, confined to a wheelchair, his right arm strapped down to a board so it wouldn’t fall limp at his side.

Dad as angel in church operetta; note chair legs made into “harp.”

But he was cognizant of the world around him, observant of events, and of other’s emotions. He communicated with us, expressing his feelings or reactions to what was going on with appropriately inflected “ba-ba-ba” sounds.

With no speech, half-paralyzed, he would be unable to call for help if an emergency arose, so someone always had to be with him.

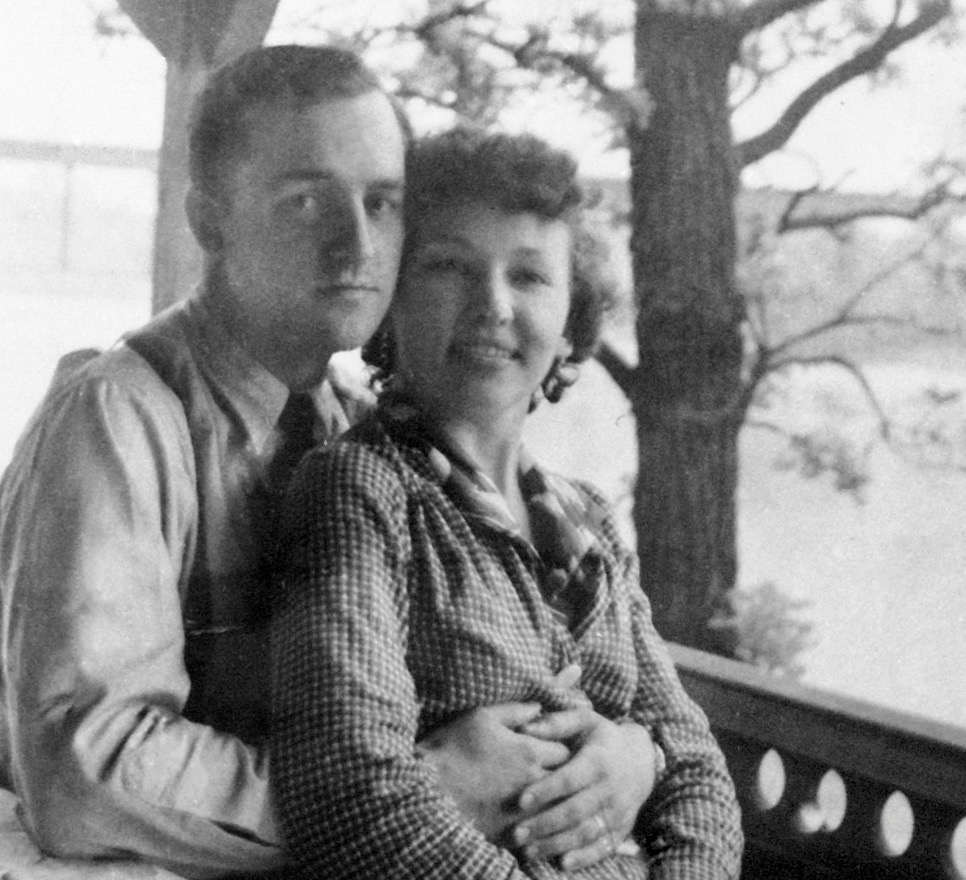

Dad and Mom shortly before their marriage, 1942

I went to the kitchen to say hello. “Hi, Dad. You’re not feeling well?” I asked.

He shook his head. After Mom left, Dad and I watched TV on the small television set placed on the kitchen table. After a few minutes, he turned off the TV and pushed back his wheelchair, indicating he wanted to lie down.

I wheeled him to the hospital bed Mom had set up in what was our former “music room” and helped him get into the bed. Despite how completely his life had been compromised by the stroke, he seldom acted glum. I was worried.

Dad, the chemist

Energetic Youth

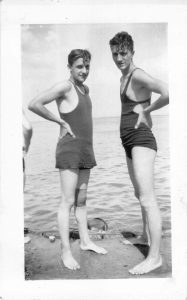

Dad, Fred Gartz, left, about 14, with older brother, Will, at North Ave. Beach.

Dad had always possessed endless energy. As a teen and young man, he did it all: worked with his immigrant dad to shovel coal and snow, clean apartments, do repairs, and much more for the scores of apartments for which his dad was janitor and manager. With his church group and at school, he swam, fenced, rode bikes, and joined hayrides in summer and sleigh rides in winter.

Around-the-clock-work

After he had turned our two-flat on the West Side into a sprawling rooming house, he and Mom worked around the clock to manage it all. Later another two-flat and eventually, a six-flat, added to their endless work. This was all this despite having to travel half the year for his job as an engineer with the National Board of Fire Underwriters.

Multi-skilled

As a child, I thought there was nothing my dad couldn’t do. Besides the hundreds of repairs and renovations he made to our two-flat, he also wrote lovely poems–sometimes just for the pleasure of writing, sometimes for friends; some were love poems to Mom, and one was a lovely poem for me on my tenth birthday.

Dad and Mom wed: Nov. 8, 1942

Always fun

But it was his shenanigans and love of fun that I remember most. He brought home a menagerie of pets over the years. At one time or another (or at the same time), we had the usual dogs and cats (often pregnant), rabbits, a flying squirrel, two gamboling ferrets, a baby hawk, a crow, a lamb, a boa constrictor named Lucifer (he raised rats in the basement to feed the snake), at least two raccoons, one of which he had freed from an illegal steel-jaw trap set in a forest preserve.

Travel

Disneyland, CA, 1959

Most summers Dad planned a week of car-camping for the family at Devil’s Lake, Wisconsin, and in 1959, an unforgettable five-week road trip south to Texas, across the Southwest, north through California and back east via Colorado. We hit all the highlights along the way, indulging in a giant smorgasbord of “America’s Greatest Travel Hits.”

When Dad finally landed a Chicago-based job, he worked mostly with men twenty-to-thirty years younger than himself. They called him the “eccentric” because he always viewed the world through a fresh lens, coming up with sometimes whimsical, sometimes wacky ideas–as long as they generated laughs and fun. The young guys always included him in their after-work bar-hopping because to them, he was just “one of the boys.”

Mom and Dad on their tenth anniversary (ten mums) 11-8-52 West Side

Three decades ago today

After I helped Dad into bed that night thirty years ago, Mom arrived home earlier than expected. She said she’d had “a feeling” that she should get home, knowing Dad hadn’t felt well. Dad kept shaking his head, saying “Ba-ba-ba” in a disconsolate tone. Mom called his doctor, who, amazingly, was in the neighborhood. He actually still made house calls!

After arriving and greeting us and Dad, the doctor pulled out his stethoscope, breathed on the metal disc to warm it, and placed it against Dad’s chest. Dad looked down at the disc, his expression calm and interested. Within about thirty seconds, Dad began shaking violently, as if in the throes of an epileptic seizure! His face turned bright red. He shook for about twenty seconds then slumped, unconscious.

“Call 911,” the doctor called out. “Full cardiac arrest!” Mom ran to the phone. The doctor and I dragged Dad to the floor, and I began CPR. The doctor raced to the phone. As I switched off between chest presses and breaths into Dad’s mouth, I checked his eyes. They were open but empty. I knew he was gone. But I kept at the CPR until the paramedics came.

“Back,” one called out just before they pressed the defibrillator against his chest–one, two, three times. No response. They lifted him onto a gurney, wheeled him to the ambulance, and drove to the hospital. Mom and I drove together to meet up with them.

There we received the news I expected. Dad was dead.

Mom and I hugged and cried, but knew we now had to move into planning mode: call the brothers, inform friends, make funeral plans.

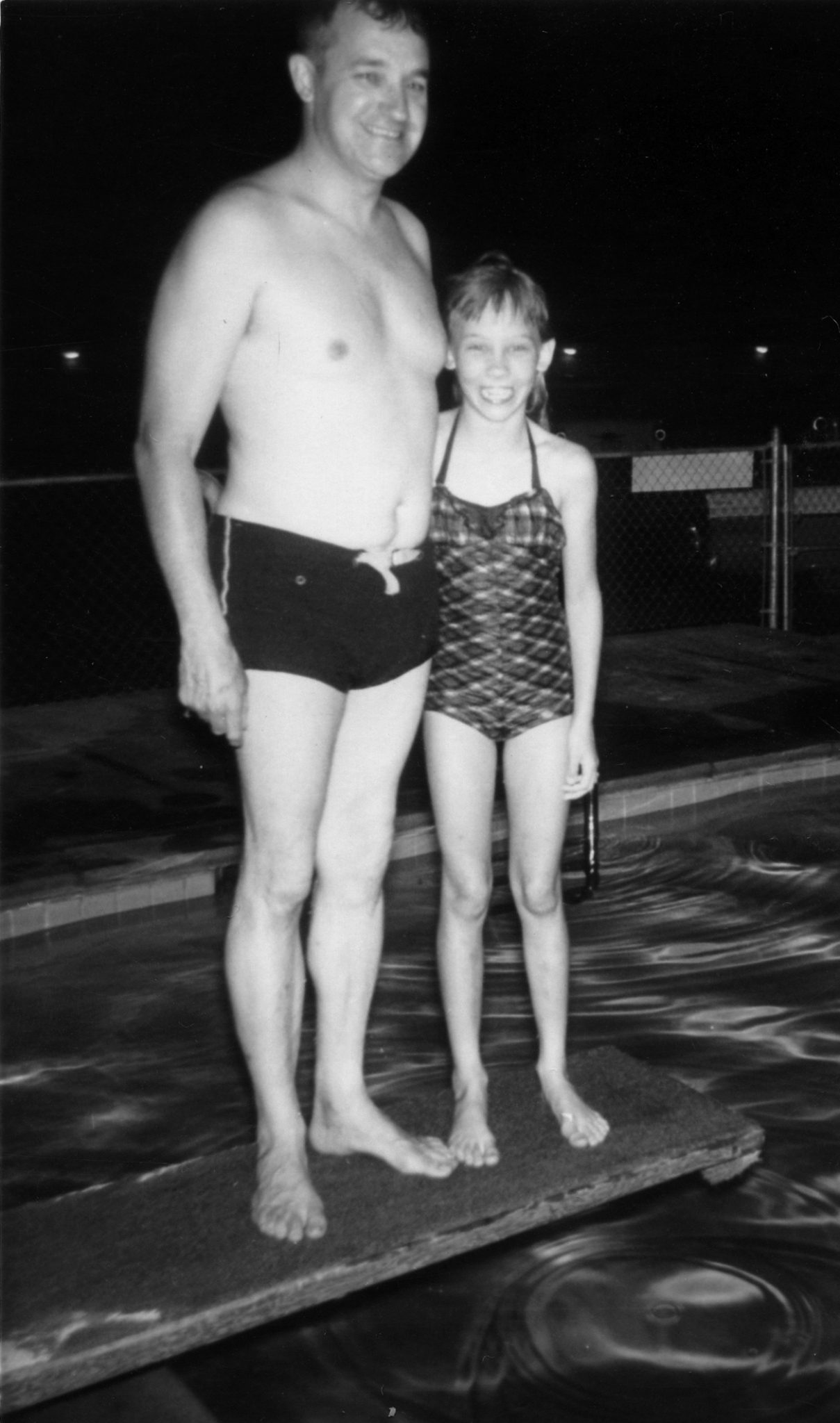

Dad and I after swimming lessons. I traveled to Enid, OK with him on a business trip, 1958

I had already mourned and grieved for Dad after his stroke. That’s when so much of him was taken from his family–and from himself. I now felt that he had been freed from his suffering; that his bodily essence would return to the earth, eventually to become one with the stars, to shine, as his life had for me, for all eternity.

The circle of life

Two weeks after Dad’s death, a new baby entered our lives through adoption–the glorious gift of our second son, Sam. It seemed as if the universe had conspired to reassure us: life goes on.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

ORDER NOW:

What a wonderful man and you bring it all to life today.

Thank you so much for reading! Merry Christmas! Linda

you are so fortunate to have all those memories and family photos to back them up!

I do feel very lucky. Thanks for reading! Linda

That a beautiful tribute! And I love all the photos!

Thank you for reading, Annette. Sorry I was so slow in acknowledging your kind words! A belated Happy New Year!

Redlined was my favorite book read in

2019 and was thrilled to attend the

presentation at the Freemont Library.

It answered many questions since I too lived in Garfield Park right by the GP

Conservatory in the forties. My grand-

parents lived there until 1959 when

they passed on in Jan. and Dec.

Please answer me, Linda. I love

that you wrote that book. Muriel

Pearson in Grayslake.

Dear Muriel,

Thank you so much for your wonderful comment, Muriel, and I apologize for this late reply. I’m so happy to hear that “Redlined” resonated with you. I’ve heard from many people who grew up in the Garfield Park area and how the book brought back so many memories of that area and era. I loved reading your comments. Thanks for reading and writing to me.