When the anniversary of the 9-11 attacks draws near, my mind leaps back to images of the First Responders, laden with gear, climbing up the stairs of the twin towers as everyone else was coming down, helping victims to escape, then later covered in white dust from the collapsed towers. I’ve been thinking about all the lives lost that horrid day sixteen years ago, including the lives of First Responders, the fire fighters who put their lives on the line every day.

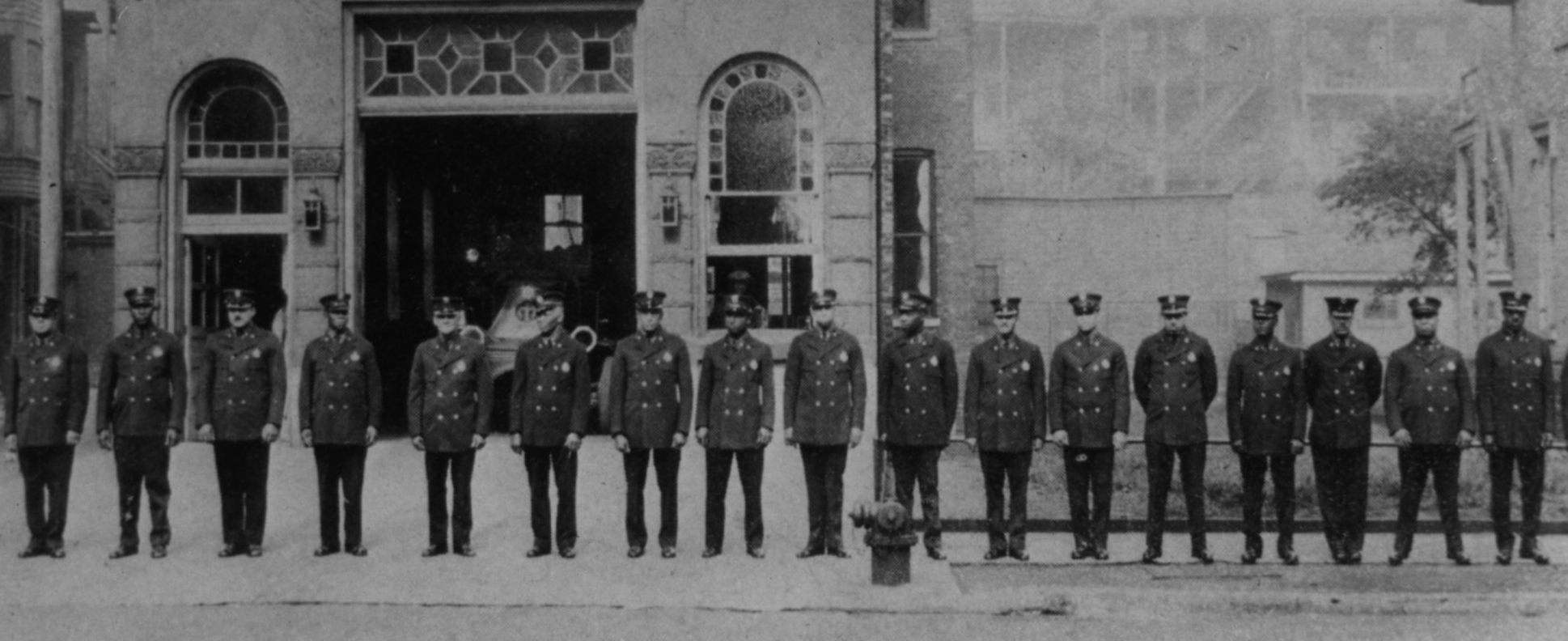

African American fire fighters ~ 1940s

I wanted to call special attention today to the history of a group of first responders whose bravery has often been overlooked. In Chicago, some retired fire fighters have worked together to create a museum to honor many that history has been left behind: The Chicago African American Fire Fighters Museum.

Last summer I had the pleasure of meeting one of the fire fighters who had helped to make the museum a reality. Dekalb had seen the article I had written for the Chicago Tribune’s “Flashback” section on the 50th anniversary (August 2015) of the first riots in my West Garfield Park neighborhood.

As reported in the article, Fatal Fire Truck Accident Sparks Riot, a hook and ladder truck sped around a corner, but the tillerman, who controlled the ladder never made it onto the truck. It swung free, killing a young black woman on the corner. “It was the last straw,” said Mary Nelson, of the Fire Department’s carelessness. She had moved into West Garfield Park within days of that tragic accident to help build up an already-suffering neighborhood.

Chicago Fire Firefighters from the CAAFFN

The problem was that the fire department in 1965 comprised only white men, and they had proved insensitive, at best, to the needs of the community, which in just two short years had transformed from predominantly white to mostly black. Various community groups had appealed to the city to assign African Americans to the Fire Department, but their requests fell on deaf years.

One black woman, whom I had interviewed about the era and who had lived in West Garfield Park at the time, told me, “The services you expected would be there for you as a white person-were against you as a black person.”

Because I had written about the fire department, Dekalb reached out to tell me about his efforts to start the museum to honor black fire fighters. I suppose one could say, “Why have a special museum for black firefighters? Just honor all fire fighters!”

The problem that I see with that position is that for so long blacks were treated abominably by their white counterparts. I personally knew (from my school days) a white fire fighter who was among the most racist people I’d ever met. He and his fire-fighting buddies regularly used the “N” word, and made a variety of racist assumptions (revealed through “jokes” or just talking) about blacks (i.e., they’re all lazy, they’re all on welfare and food stamps, they have too many babies, they’re natural criminals, etc. You get the idea);

Fire fighter at work.

After years of being marginalized and not recognized for the many contributions they had made at every stage of American history, blacks want to show their children a history that isn’t focused only on white achievements. The Chicago African American Fire Fighters Museum now honors the brave African American First Responders. Neighbors and visitors can see some great old photos and put history into perspective.

The CAAFFM is located at 5349 South Wabash, Chicago, IL 60615 • Ph: 773-262-3210

Read more about racially changing communities and the conflicts between blacks and whites that arose over housing in my upcoming book:

Redlined: To be published by

She Writes Press: April 3, 2018

Terrific post! Can’t wait to read your book!

Thanks, Maggie!

Linda

I am a First Responder/ Paramedic

Hi Joni,

Thank you for your service and comment. Such a critical job!

Thank you so much for your work in this field. I’m sorry I’m so delayed in replying. I do appreciate your dedication and work.