Grosspold Family Book

My grandmother kept a photo of her hometown church tucked into the hymnbook she brought with her from Romania. No wonder. That church was more than just a place of worship. It was the repository of her entire community’s history. That’s why my brothers and I made the Grosspold Lutheran Church a crucial stop on our roots-finding mission to Transylvania/Siebenbürgen in 2007. But we had no idea just what we would discover.

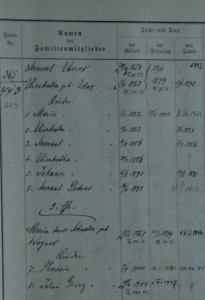

After finding the Ebner family house number (403) during our background research in Hermannstadt/Sibiu, we arranged to meet the Grosspold church’s minister, Pastor Meitert, who presented us with enormous volumes of ancient ledgers and narrowed down our grandmother’s family to this one. Centuries of handling is worn into its cover on which is handwritten: Familienbuch Grosspold [Grosspold Family Book].

Like churches throughout Europe, the Lutheran church in Grosspold encapsulated the lives of its parishioners in columns and dates maintained in “Family Books.” A sense of life’s harsh calculus in 19th century Europe emerges from those stark numbers.

Pastor Meitert used the Ebner “house number” (Grosspold has no typical street addresses — only house numbers) to search the book, and began turning the pages. History was literally unfolding before our eyes. At the top of page 283, the name “Samuel Ebner,” my grandmother’s father, was handwritten under the heading, “Name of Family Member.”

Samuel Ebner Family-Page 283 in Familienbuch

Here’s page 283, photographed at the church.

Under Samuel’s name is “Elisabetha Ebner, geb. Eder” [née Eder], my grandmother’s mother. The next three columns record the “year and date” of each family member’s birth, marriage, and death. (I cropped out additional columns with little info to make viewing easier). The entries show Samuel Ebner was born December 20, 1854, and married Lisi’s mother, Elisabetha Eder, on November 23, 1879. He was 24. Born September 3, 1863, Elisabetha was only 16.

Their first child, Maria, arrived about two years later, February, 1882. What good news this book holds! I imagine Samuel and Elisabetha’s thrill. But then the entries turn tragic. The next baby, born in December, 1883, was named Elisabetha, after her mother. It was winter. She died three and half weeks later. A little boy, Samuel, bearing his father’s name, was born in April,1886. The book records he died July 2, 1886, living only two months.

Names were assigned to children over and over until they could stick. My grandmother was given the same name as her deceased sister, Elisabetha. But the book erroneously records her birth as July 30, 1886, impossible since baby Samuel was born three months prior to that date. The year should have been 1887. A good archaeologist has to be sure even recorded history makes sense! But it makes me wonder. Was the pastor pondering little Samuel’s birth and death dates when he absentmindedly entered the wrong year for my grandmother’s birth?

Only 23 when my grandmother was born, my great-grandmother had already suffered through the deaths of two children. But more heartache for the family was to come. In May, 1890, little Johann was born. He lived one year. My grandmother would have been nearly three when her baby brother died. Her parents’ grief must have affected even a child so young, but she never spoke of it. She would have plenty of other losses to hold in her heart.

Elisabetha gave birth again in June, 1893, another little boy, again named Samuel. But his mother never got to see her only son live to grow up. Death bypassed Samuel—for the time being—and sought out his mother this go-around. On January 13, 1898, thirty-four-year-old Elisabetha succumbed to what Grandma later told us was pneumonia.

Grosspold Church’s Family Book shown to brother Bill and me by Pastor Meitert

The book doesn’t record the cause of death, but in an era prior to antibiotics, disease was the likely culprit for every death the Ebners endured. In this one family’s ancient record, we see first-hand the kind of loss endured by virtually all families of that time.

Left motherless, Lisi (my grandmother’s most common nickname) clung ever more tightly to the father she adored. But then she felt he, too, was taken from her. What happened next spawned an amazing coincidence a century later to be explored in the next post.

Grosspold Lutheran Church rising above townscape

This last report reminded me of a conversation I had with my grandmother. She was 103 when she died last year. She said that people today don’t understand how devastating it was to loose a child. She thought that people today discarded to some extent a mother grief because in the olden days families could be quite large. My grandmother pointed out that no matter how many children survive you always long for the ones who didn’t make it.

Diana Shoemaker

So true, Diana. We think today that just because death was more common in the past, that people didn’t suffer as much. They had to learn ways to cope (deep religious faith helped many), but the loss was still devastating. We can learn today from their strength to keep going. Next post will highlight the kind of philosophy that underlay their fortitude. Thanks for the comment!

This entry, with its “accounting” of births and deaths brought tears to my eyes. As suggested in your earliest post, I could feel this record resonate with what I know of my own family’s history – the births and deaths of my parent’s siblings, from such simple diseases (by today’s standards) as flu or “Second Summer Complaint”. Thanks for this story, Linda, it is such a tribute to your family and inspires me to organize what I do know of my own family’s history into something as cohesive as this. I am enjoying reading this family history, having been one… Read more »