When an assassin felled Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4th, 1968, it was not just the murder of the greatest leader of the Civil Rights Movement, it was the murder of hope for so many of our country’s African American citizens.

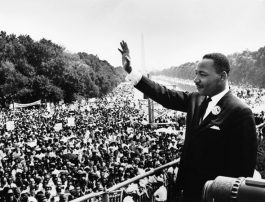

An iconic photo of Dr. Martin Luther King, March on Washington, Aug. 1963

It also was the death blow to the community in which I’d grown up, the community of my father’s childhood, the community in which Dad’s parents had settled as young, hopeful immigrants in 1912: West Garfield Park.

By 1968, most whites had fled WGP, a community that in 1960 had been about 84% white. The racial turnover during the 1960s was rapid and complete. By 1970, WGP’s population would be nearly 97% black.

We moved north in 1966, but my parents didn’t sell their three small apartment buildings on Washington Boulevard, all within a half block of Keeler Avenue. Instead they continued to nurture their tenants and property, as they always had.

Today’s brief sneak preview from my book is in honor of Dr. King’s memory. It’s based both on research and entries my mother made in her diary at the time.

From Chapter 33:

On April 4th [1968], an assassin gunned down Dr. Martin Luther King as he stood on the balcony of his hotel room in Memphis, Tennessee. Riots exploded in cities across the country. West Garfield Park again went up in flames, but with far more destruction than in the 1965 riot. [A young African American woman had been accidentally killed by a fire truck driven by the all white local fire department.]

Looting and arson engulfed the community where I had walked and played. One of the six-flat tenants called my mother as the mayhem unfolded that first night. She told Mom she had just returned from taking her husband to Garfield Park Hospital. On his way home from work, he had been ensnared in the rioting and shot in both hands. . . .

Years later, I talked to Barbara Lilly, an African American woman and member of my former church, Bethel. She had moved into West Garfield Park about the same time we’d moved north. After more than forty years, the 1968 riots were still seared in her memory. Here’s what she recalled:

People were burning up houses. They were just rollin’ clothes out of Robert Hall [a Madison Street clothing store]. . . . The National Guard was right there. . . . They had tanks in front of my house and down the streets on West End. I had to get my kids out of school. My kids saw all those tanks going down West End and said, “Look, Mommy! Look! What’s that?” Then at night, when we looked out the window, you would have thought it was Vietnam

Neighbors climbed up to their rooftops for a better view of the eastern sky, where flames stabbed through swells of rolling black

Barbara Lilly also recalled that mayor Richard J. Daley commanded his police, “Shoot to maim looters and shoot to kill any arsonists.” The order outraged many in Chicago, but it especially incensed African Americans like Lilly.

“It was terrible,” said Barbara Lilly, as she recalled the riots. “We were already devastated by the whole thing. He’d a never given that order if they’d been white.”

Lilly said of the rioters after King’s death, “They were just destroying their own. I guess they felt they didn’t have anything else when Martin Luther King was murdered—like he was their savior. . . . [After the riots], A&P and Madigan’s . . . a Jewel . . . all prominent stores—Robert Hall, Fish Furniture—all those stores left. We had to go out of our community to shop.”

While the riots and flames engulfed the West Side, Mom and Dad drove to the six-flat to fix a furnace problem. Annette Branch [a tenant] greeted my parents with more bad news, her voice frayed with fear. “Someone got shot just north of the six-flat—right here on Keeler Avenue,” she said.

Dad patted the gun in his waistband. “We’re being extra cautious,” he assured her. . . .

Two weeks later, my parents’ last white tenant, elderly Mrs. Dilzer, moved out.

End of sneak preview

Newspaper columns and essays have been honoring Dr. King, as we approach the 50th anniversary of his murder, and remembrances will continue to pour in over the next days and weeks. In the collective consciousness, he is revered.

But I recall the fear with which many whites thought of King. He was called a “trouble-maker” and “rabble-rouser”- for daring to seek fairness and justice for African American citizens.

Even after King’s death, there was tremendous resistance to honor his memory. U.S. Representative John Conyers called for a national holiday eight days after King was killed. But it took fifteen years for that to happen.

At the White House Rose Garden on November 2, 1983, Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King. It was observed for the first time on January 20, 1986.

King had to fight for every little piece of success. He was beaten, jailed, vilified by many whites, and secretly taped by the FBI. The riots that broke out in cities across the country reflected the loss of hope many African Americans experience. The man they had revered, their “savior,” as Barbara Lilly said, the man who had sought peaceful means to cash our country’s “bad check” to its black citizens, had been murdered by a white man.

King’s search for peaceful justice was answered with a bullet. We should honor his memory for his courage to stand up against hate, to keep fighting when he always knew there were those who wanted him dead.

Please share your memories of what you recall of King’s death in comments.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

I was a sophomore at NU at the time, and in retrospect rather sheltered and clueless about the full impact of this tragedy. The campus was shut down for the weekend. There was also a curfew imposed in Chicago, with a $500 fine if you were under 21 and caught outside after hours. A bunch of us went to a party in Rogers Park that Saturday night, and drove around very nervously, as we had a carload of a couple thousand dollars in fines had we been stopped. Nothing happened. Much later I realized that the Chicago cops had much… Read more »

Hi Barbara, So sorry for this tardy reply. It seems that I never get notified of comments. So we were at NU at the same time and same class – as I was a sophomore too. I recently (5/4) attended the 50th anniversary of the black takeover of the Bursar’s Office, which was just 1/2 a block from my dorm at the NU Apartments. I’m sure you remember that as well, another offshoot of MLK’s murder. LOTS of people attended, and one of the presentations featured two of the people who had been in the planning stages of the takeover,… Read more »