Monday, January 15th, our country will celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day, this year the actual date of his birthday. It takes me back to the day of his “Dream” speech, when Jim Crow was fighting to keep blacks separate and unequal, and just two months after the first African American family had moved onto our block.

It was the same year fire hoses and dogs assaulted young black peaceful in Birmingham, Alabama, in May; when in June, Governor George Wallace of Alabama had stood defiantly at the entrance to the University of Alabama to keep out black students, whose taxes were used to help pay for the school, until President Kennedy sent in federal troop to make Wallace back down.

A day after that confrontation, Medgar Evers, a field secretary for the NAACP, was gunned down in his driveway in front of his horrified wife and little children.

Martin Luther King, March on Washington.

Two months later, on August 28th, 1963, millions of Americans heard Martin Luther King’s poetic demands for racial justice. Whites throughout the country tuned in to listen or watch the March on Washington, either rapt in the power of his metaphor or furious and disdainful of his dreams. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI at that time labeled King “the most powerful and therefore, the most dangerous Negro in America.”

We watched King’s speech at our home in Chicago’s West Garfield Park neighborhood, the community where my paternal Grandparents had settled in 1912, raised their children, and where my dad and mother raised my two brothers and me, as well. West Garfield Park had been home to the Gartz family for the previous half century, a time span prior to King’s speech equal to the time that has now passed since he so eloquently and passionately called on the nation for racial justice.

The previous fall, in 1962, school boundaries had changed in our community to alleviate over-crowding in the Chicago schools in black neighborhoods. The change brought an influx of African American students from south of Madison walking through our still-white blocks. In one year, the population of my former grade school was reversed, from 95% white, when I graduated in 1962, to 57% black by graduation day in June, 1963.

On June 22, 1963, less than two weeks after Medgar Evers was murdered, the first black family bought a home on our street, in the 4200 block of West Washington Blvd. By the time King gave his speech, two months later, four houses had been sold to African Americans. It was the beginning of a mass white exodus.

As Amanda Seligman quotes in her excellent book Block by Block, which examines the racial change in West Garfield Park, one anonymous “Homeowner” questioned the concept of integration as addressed in comments to our neighborhood newspaper, The Garfieldian. “Homeowner” wrote, “From your words one can only conclude that for you it is the time between when the first Negro family moves in and the last white family moves out.”

Chicago was (and still is) a notoriously segregated city. Blacks were all but invisible to whites as a presence in American society. No black actors were featured on any serious television show in 1963. (It would be two more years until I Spy broke ground in 1965 as the first television drama to feature an African American when Bill Cosby teamed up with Robert Culp). Virtually no blacks were in government. Magazine ads or billboards with blacks were non-existent (unless in an African American neighborhood or a magazine, like Jet or Ebony, geared specifically to blacks, where no whites would see them.)

The March on Washington and the Civil Rights movement in general put the demands of and injustices suffered by blacks front and center in the American consciousness.

But most whites, whether liberal-minded or racist, didn’t personally know any blacks. We didn’t either.

All that changed for us the summer of 1963. It was an era of red-lining, block-busting, and fear-mongering. Calls would come in the night. “They’re coming.” Click. No clue who called. Flyers appeared in our vestibule: “Sell now before it’s too late.”

We owned two 2-flats and frankly, we were afraid. Whites understood that when a neighborhood “changed,” property values dropped. That’s why in two months, four houses on our block were sold to blacks. Whites weren’t buying any longer in West Garfield Park. Aside from prejudice, whites wanted out before they lost their property investment.

We stayed.

Within days of the first blacks moving onto our block, the son in the new family, Junior, and my brother, Billy, began playing together at each other’s houses. Martin Luther King’s dream, of “one day… little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white girls and white boys as sisters and brothers,” had come to pass on our block as a result of integration. My white brother and black Junior became fast friends.

The integration of our neighborhood wasn’t all brotherhood, sweetness, and light, however, and it would be a lie to pretend all prejudice disappeared, that no conflict emerged, and everyone lived in harmony. Still, what King envisioned in his Dream speech at the March on Washington in 1963–the opportunity to forge friendships beyond racial stereotypes––had come to pass as a result of our integrating neighborhood.

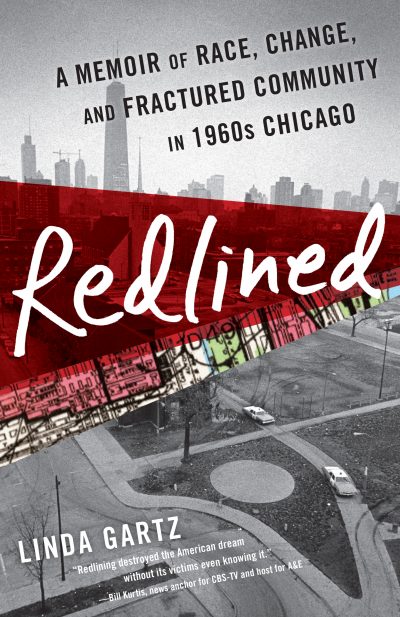

How long would it be, however, as “Homeowner” opined, before the last whites left? You’ll find the answer in my book, Redlined.

Did you live through Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s? If you did or didn’t, what do you think of race relations now in America?

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.