“I’m an executive!” my mother shouted at her family. “But nobody respects what I do!”

An executive? We sniggered. My dad was blatantly dismissive. My brothers, and even I, a young woman in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, thought she was losing her marbles. But the woman’s movement hadn’t really hit with full force yet, and I couldn’t have applied it to my mother anyway.

But after reading my parents’ letters and diaries, I realize Mom indeed was an executive. Like so many intelligent, ambitious women of her era, her talents were neither recognized nor rewarded.

A window into the past

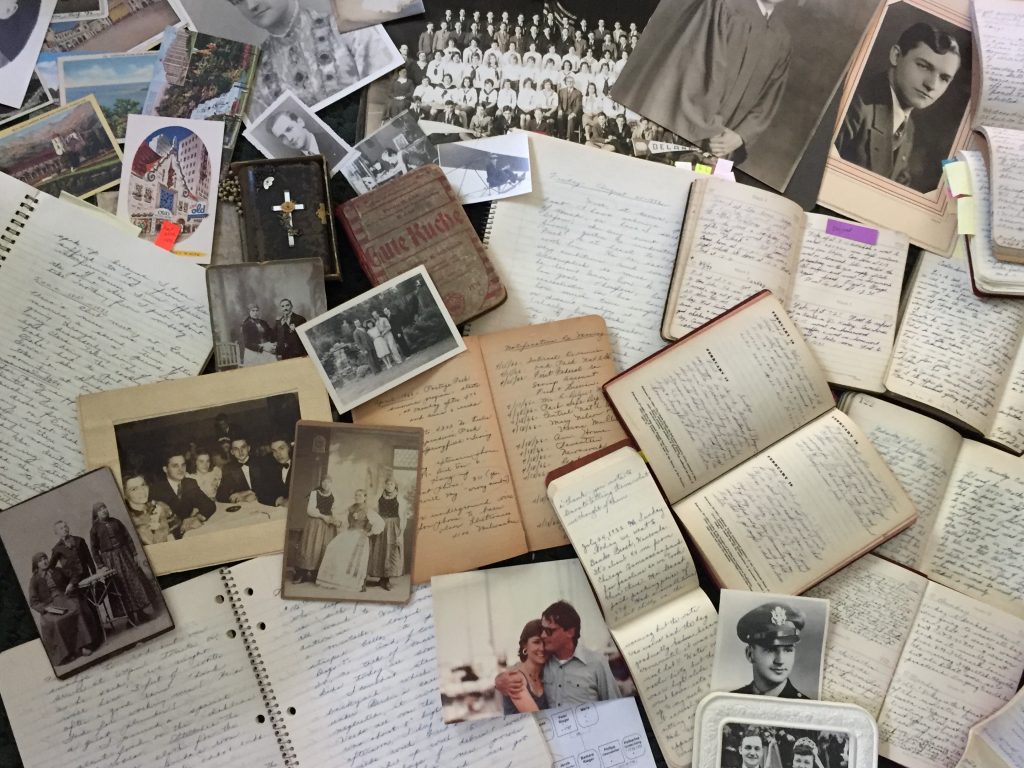

If you’ve explored this website, you know that after Mom died, my brothers and I discovered thousands of pages of letters, diaries, documents, photos, and much more in the attic of my former home. We ended up with twenty-five bankers’ boxes–with just the good stuff. Then filled a dumpster to boot.

A tiny sampling from one box of the archives.

Writers and Savers

My parents both kept diaries, and these treasures are a window into their hearts and minds spanning more than sixty years. Reading through their writing, I became privy to the details of their relationship before I was born, and as a child. I was to young to have comprehended the choices they made that, over time, undermined their marriage.

“He saddled me with that rooming house!”

I heard this bitter complaint often from my mother starting when I was a teen and young adult, but dismissed it, just as I dismissed her claim to be “an executive.” What was she talking about?

Our two-flat on Washington Blvd.

Sure, I grew up knowing that the 2nd floor apartment of our graystone two-flat consisted of five rooms, rentable to only men, who all shared one bathroom, pension-style. The back end of the former single-family apartment comprised a kitchen, bedroom, bathroom and “dining room,” converted to a “living room” with a sofa-bed. In the basement were three studio-type apartments and only one bathroom shared by all the renters.

We also rented out two of the bedrooms in the same apartment in which we lived. My maternal grandmother, Grandma K, slept in the dining room, as did my brother, age three. (I was a baby in a crib when we moved into our new home. When I outgrew the crib, I slept in the dining room too).

Panic: job loss

To top it off, Dad lost his job right after we moved into our new home. Two little kids, a mortgage, and no income. After a summer of fruitless searching, both my parents felt the panic of their financial straits. Dad finally accepted a job with a company that required six months of travel per year.

Who would be responsible for all the headaches, repairs, deadbeats who didn’t pay their rent, and financial details to run this rooming house? My mother!

Grandma K, Mom’s mother, lived with us, so she helped with cooking, cleaning, and the care for two little children, but Mom managed the business, hung “Room for Rent” signs on the front door, interviewed and screened potential tenants, collected the rent, and recorded income and expenses. Every year she filled out the increasingly complex income tax return on her 1940s Royal typewriter, with three or four carbon copies.

“What’s wrong with her intelligence, anyway?”

I discovered in the letters they wrote to each other while Dad traveled what I hadn’t known as a toddler. In 1951, Dad was gung-ho to convert the front end of the basement to three studio-like apartments.

Mom’s letters show she was adamantly against this plan. She laid out her arguments, which went something like this:

• They were doing fine financially with just the rented rooms upstairs and in their own apartment.

• She told Dad he had no idea how much work the house was. (She had to clean the men’s rooms once a week and change the sheets in addition to cleaning our own house, painting, and varnishing, shopping, and all the other “women’s” chores of the era: laundry, hanging it out on a line (no dryer), shopping, cooking from scratch, etc.

• She laid out the finances and the work involved:

- They’d have to take out a $7,000 load, almost half the cost of house

- It would take years before they broke even, and that’s if the apartments were always rented.

- She would have to show the apartments to potential tenants and clean them after tenants moved out.

- The common bathroom would have to be cleaned once a week,

- She laid out the figures, showing the cost and expenses and time involved.

- Dad was traveling, and she’d have all the responsibilities for overseeing the construction and managing the apartments after they were created.

Mom and Dad happy together, 1956, Caruso’s Restaurant, Chicago.

In his letters, Dad responded politely. His main argument was: “We’ll make $45 per week with no work on your part.” No work?

In his diary, Dad totally dismissed all her carefully laid-out figures and only vented, “What’s wrong with her intelligence, anyway?” Well, there was nothing wrong with her intelligence, but for some reason, Dad was obsessed with getting these apartments. (Read Redlined to find out more.)

Dad prevailed, mainly, I’m sure, because Mom didn’t want to see him unhappy. She still loved him. But her every prediction came true.

Mom, astonished at something-with a view from kitchen through dining room to living room of our “shot-gun” first floor apartment.

The Executive

Mom managed the whole crazy enterprise. When they bought another two-flat, she added that to her managerial duties. In 1965, my grandparents suddenly moved to a suburb and gave my parents their six-flat. Instead of selling it, they fixed it up, and Mom managed that too.

As the community sank into more poverty and devastation after the Martin Luther King riots of 1968, more and more work was needed to keep up their buildings.

Break-ins became more common. Mailboxes were pulled out of the wall in the vestibule until Dad had to install a heavy-duty, exterior bolt-lock door. Dad was on hand every weekend for maintenance, but Mom recruited, organized, scheduled, and oversaw every repair, every conversion, every bit of construction.

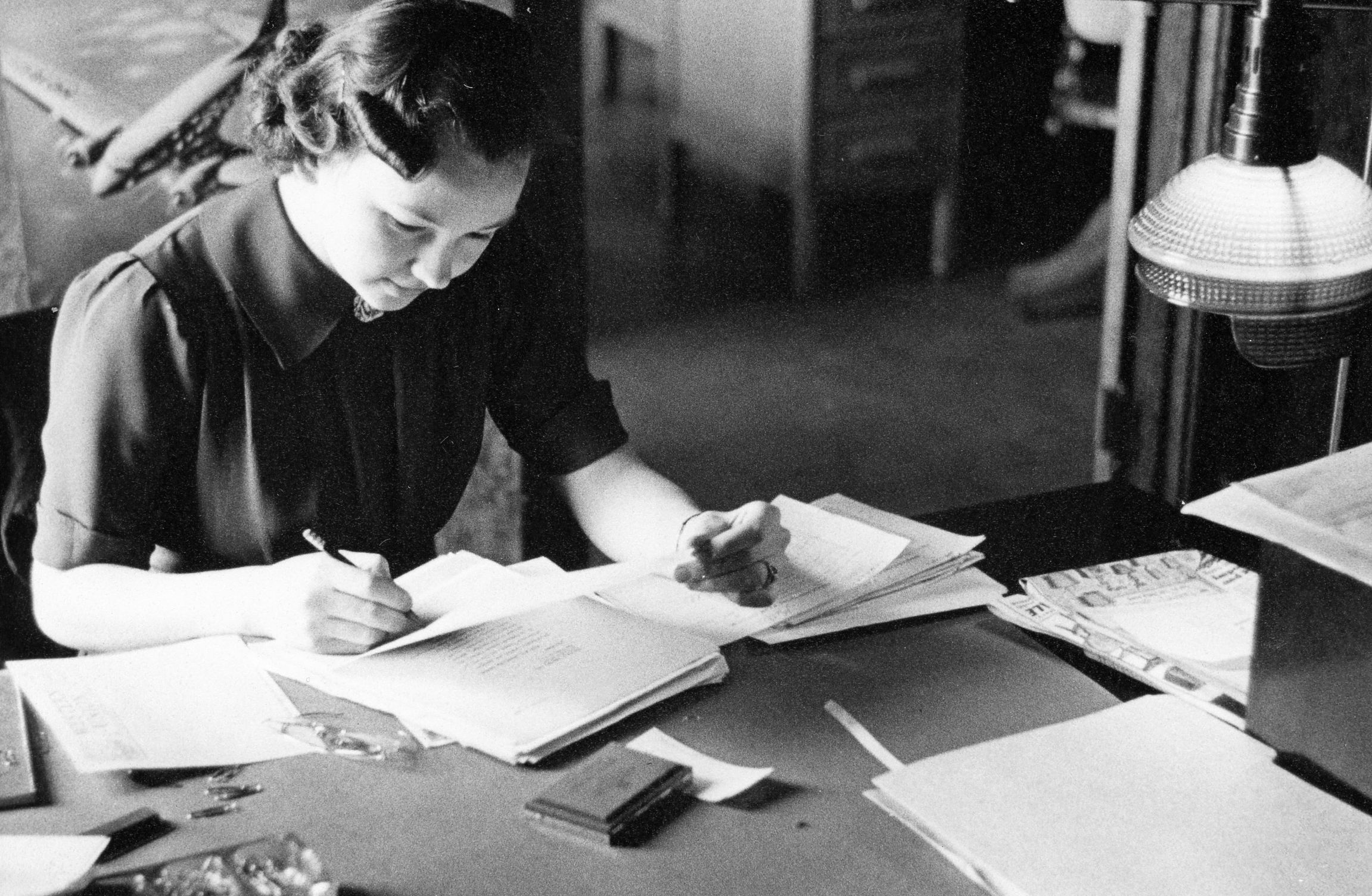

Mom working at the Bayer Company for Mr. Gibney, her exacting and obstreperous boss.

Mom really was an executive. She had formidable skills honed as the secretary to the President of the Bayer [Aspirin] company for nine years.

Her boss had to hire two women to do her work when she quit to have her first child, my older brother. At home, she still was responsible for all the “women’s work.”

Mom with newborn baby, Paul. My Grandpa Gartz hamming in background. Typical of era: women hung laundry on the line. July 1946

On the income tax, she lists her profession as “housewife.” That just galls me. Her managerial work made a tangible monetary contribution. The rentals nearly doubled Dad’s salary. (Then there was the “housewife work,” “women’s” work, she was never paid for.) She was a financial manager. An executive.

For Women’s History Month, this is a shout-out to all the under-appreciated , super achieving women, who never got the credit they deserved.

Read more in my book, Redlined.

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

Just terrific and so accurate, my mom was stay at home but my dad cheerfully adopted the term of ‘crap carpenter’…every time he put up a shelf, it fell down! My mother made them stick, painted, canned, cooked, took care of me…a big job as she was my stepmother and I treated as so for a long time…my grandmother, all 5 ft, maybe, had 12 children and her husband expected her to be compliant every night. My dad loved my mom and she loved him, but it wasn’t a life of many rewards. Eventually she ran his office, at his… Read more »