I hope you’ve been watching Burns’ and Novick’s Vietnam War series, because if you haven’t, whether you lived through the era or not, it’s eye-opening. The division in America was fierce and unrelenting. Division even more visceral than political divisions today. I have vivid memories of this terrifying era and the greatest admiration for the documentarians who show the war in its complexity.

The “whop-whop-whop” of helicopters was a soundtrack of the Vietnam War

Burns’s and Novick’s challenge

Ken Burns and Lynn Novick worked for ten years to get this story right. To do that they knew they had to include the point of view and memories of Viet Cong fighters. As a documentary producer myself, I know the how hard it can be to find the right people who can represent a story.

I’m in awe of the work and dedication of Burns, Novice, and their fellow producers. Viewers and pundits can quibble about what they’d like to see more of, less of’; they can argue that we shouldn’t even hear the “enemy’s” point of view. But then the result would have been a propaganda film.

Vietnam and Civil Rights Movement 1963

America’s involvement in Vietnam was already escalating when Kennedy sent in “advisors” in the early 1960s. I was still in grade school and wasn’t reading the newspaper. The nightly television news that spring was focused on the civil rights movement.

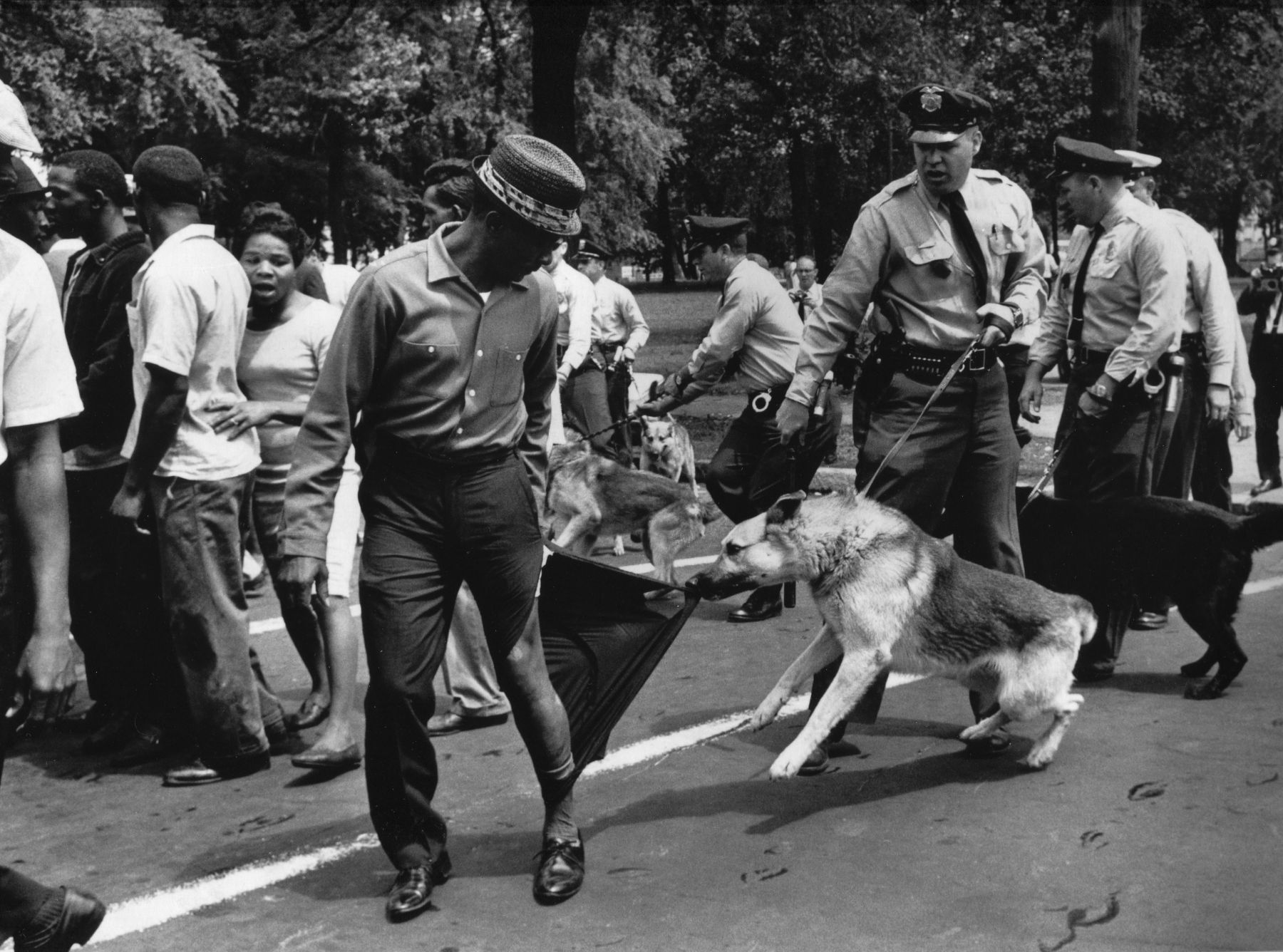

Dogs attacking protesters, Birmingham AL 1963. Image by Charles Moore

In Birmingham, Alabama, in the spring of 1963, Bull Connor (official title: Commissioner of Public Safety), turned fire hoses and growling German Shepherds on peaceful young protestors. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy sent troops to the University of Alabama to force Governor George Wallace to allow blacks to enter. Kennedy made a speech to the nation that night calling on his fellow Americans to treat our African American citizens fairly.

On that same day, on the other side of the globe, a Buddhist monk set himself on fire to protest South Vietnam’s disrespectful treatment of Buddhists. A photographer caught the grisly self-immolation on film. Americans and people around the world were horrified by the photo. The monk sits placidly on the streets of Saigon as he’s engulfed in flames. The image was seared into my pre-adolescent mind, but it was far away. What did this far-away place have to do with our lives. Within a short time, we learned.

An escalating war

Five years later, in January 1968, I had just moved into the Northwestern University Apartments with three other roommates. Tens of thousand of troops by this time were fighting in Vietnam; young men, barely out of high school. The “television war” made it seem very close to home indeed. Here’s a sneak preview of that portion of my book (in italics):

An Excerpt from Redlined

Nightly news programs beamed the Vietnam War right into America’s homes and college dorms across the nation. War was a vague concept I had studied in history class. I knew Ebner’s death after World War II had permanently scarred Dad and my grandparents, but I had experienced none of it.

Morly Safer of CBS reporting from a Vietnamese Village torched by G.I.s , smoke rising behind him.

Now TV gave all Americans an eyewitness view. Boys, my age, hunkered down in swamps; scared; confessing to television interviewers they didn’t know why they were in Southeast Asia. I saw CBS news reporter, Morly Safer, reporting from a small Vietnamese hamlet, burned to the ground by American troops. Children and elderly women, stunned and blank-eyed, wandered like ghosts among the charred ruins.

I felt sick at the images—at the thought of my brothers, friends, or Bill moldering in those swamps, killed, blown apart, or tortured in a POW camp.

I had written this portion in 2015, two years before the PBS Vietnam series aired, but it was such a stunning moment, in the American public’s realization of what some troops were commanded to do, it had to be included. (In the series, several Vietnam vets talk about their reluctance to follow orders to burn a village, or to the village’s rice store, because they realized they were destroying these poor peasants’ lives.

Here’s what strikes me thus far in the series:

a) Every vet interviewed gives the distinct impression that he felt “bamboozled” into serving in a pointless war. These were idealistic, honorable young men from wonderful, idealistic families, and their cynicism at the lies their government told them is palpable as they look back.

b) Our country is divided again. Young men aren’t dying–yet. But I wonder: when those who support the political bombast of our present era will some day have to come to terms with the lies they’re being sold, just how cynical they’ll be.

Recommended reading:

I’ve read a handful books on the Vietnam War, and many of you have undoubted read more. But here are three books that I highly recommend.

The Things They Carried, a collection of linked short stories by Vietnam veteran, Tim O’Brien.

Two of my favorites are both written by former New York Times reporters who covered the war: David Halberstam‘s The Best and the Brightest, and A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam (1988) by Neil Sheehan, about retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann and the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War.

Note: I purposely didn’t link to a site to buy the books above so as not to direct you to a particular site.

Available at bookstores as ebook, and online April 3, 2018

And will it happen again or is it already, how much longer do we have to continue to fight i Afghanistan? 11-12 years now and no sign of stopping

I am amused at how people try to editorialize war. It is horror incarnate plain and simple. War is human kind in It’s lowest form. Many centuries ago, war was considered noble and necessary. Real estate deals were often sealed with a war. The negotiations and rhetoric (lies) haven’t changed much, but the science has. Gunpowder, atom smashers, drones etc:. Wars and rumors of Wars? Who was it that said That? Surprise surprise. Must be a coincidence. I recommend a book, “The Village” by then Captain, Bing West. His account of a combined action platoon, (CAP unit). Marines and south… Read more »