“Russell Baker died Monday at his home in Leesburg, Va. He was 93.” That’s the opening to the New York Times obituary after the death of one of the twentieth century’s greatest newspapermen, memoirist, writer, and overall high quality human being. I didn’t know Russell Baker personally, but after reading and rereading his Pulitzer Prize–winning memoir, Growing Up, to the point I could quote passages verbatim, I wanted to know him. I read several of his columns, but it was that memoir that told me so much of who he was—and about the way I aspired to write, but knew I’d never attain.

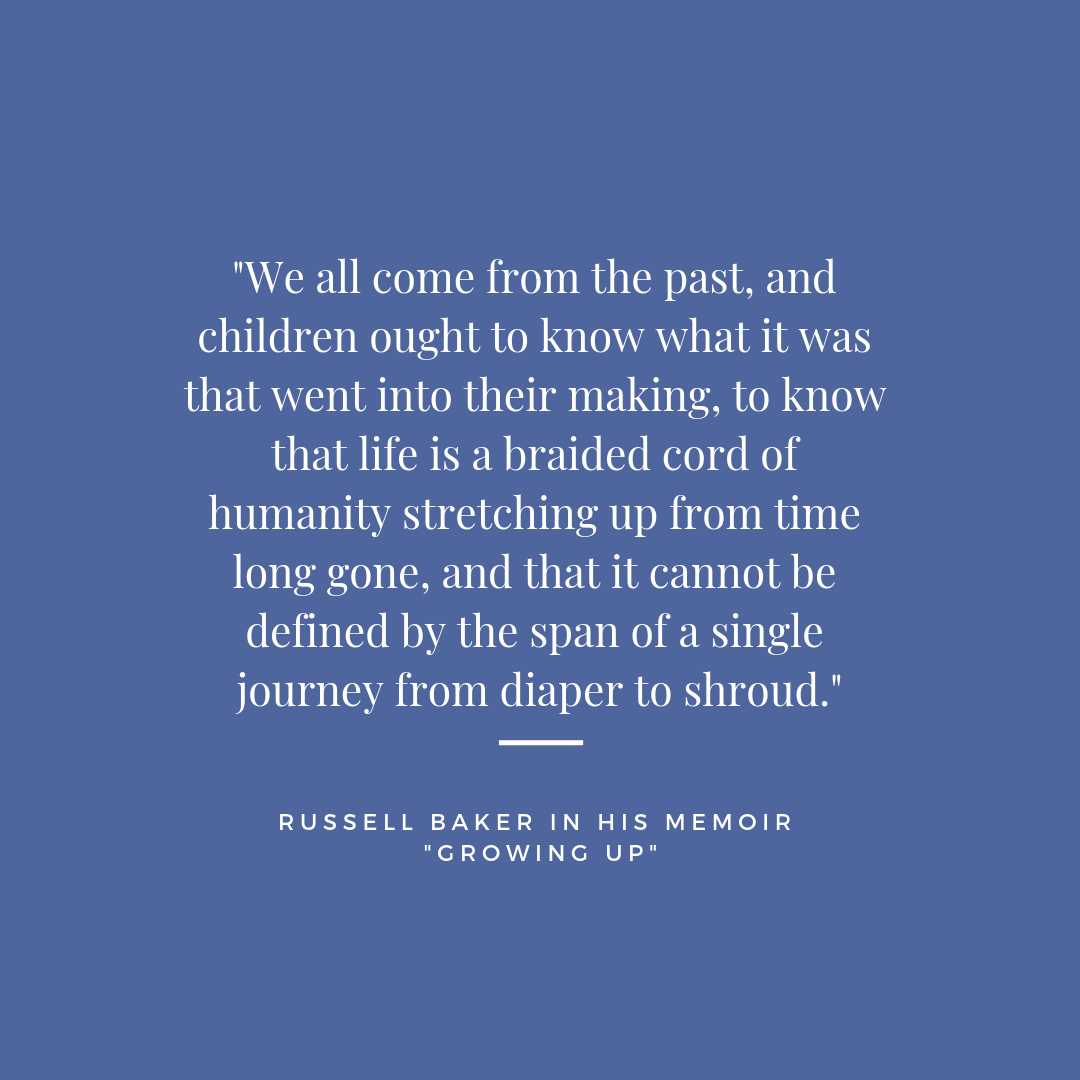

How did he do it: the self-effacing humor, poignant, and ironic depiction of casual racial injustice or blatant sexism, the effusive joy of a country boy seeing a toilet flush for the first time in the home of “big city” relatives (a smile-eliciting scene), his elegiac memories of a time past, and his wish, clearly expressed in his prologue that we all come from the past, and children ought . . . to know “that life is a braided cord of humanity stretching up from time long gone, and that it cannot be defined by the span of a single journey from diaper to shroud.”

I was gobsmacked by those two brilliant metaphors in one sentence, each maintaining its integrity throughout. “A braided cord of humanity . . .” How beautiful and perfect that that is, the interweaving of our ancestors into marriage and intertwining with their children, who in turn transform the warp and woof of their living into the fabric of life.

It’s easy to write, “from cradle to grave.” It works well (two “containers” for a human’s body, one at birth, one at death), but like so many apt phrases it’s become a cliché. So Baker finds two words that are similar in concept. He comes up with two cloths that swaddle a human, one at birth and one at death: diaper to shroud. Brilliant.

I was so mesmerized by virtually every sentence in Growing Up that I kept coming back to study his memoir over and over, to think about how his mind worked to create his metaphors and and wondering if I could work at doing the same.

I don’t recall how Baker’s memoir Growing Up came to my attention, but I know it was early on in my decision to write about my family. The letters and diaries I’d discovered in my parents’ attic after my mom’s death in 1994 had lain untouched for about eight years, after my brothers and I had organized them into twenty-five bankers boxes and stored them in my garage. In 2002, I finally answered a nagging inner voice to find out what had lain hidden for so many decades.

I started with the World War II letters to and from my Uncle Ebner (ABE-ner) as he trained to be a navigator on the B-17 heavy bomber and was instantly whisked back in time to the 1940s, as if on a magic carpet ride. My family’s letters were so full of life and such vivid writing and immediate emotion, I felt reading their letters as if I were entering a time machine to the past.

“Serious journalism need not be solemn.”

RIP beloved humorist and columnist Russell Baker. pic.twitter.com/VVGJwlNeWD

— PEN America (@PENamerican) January 23, 2019

My parents were of about the same age as Baker. My dad was ten years older, my mom seven years his senior, but my dad’s younger brother, Ebner (he was named Frank Ebner, but everyone in the family called him by his middle name) was born the same year as Baker, 1924. That fact somehow drew me even closer to wanting to understand not just how Baker wrote so beautifully, but how he evoked an era that I, too, would want to recreate.

It was an era of young people who grew up during the Great Depression, who experienced hardship, but still understood basic courtesies and duty and work. These simple middle class values weren’t questioned then as somehow an antithesis to understanding people from other classes. Russell grew up poor, the son of a single mom who pushed her son relentlessly to “make something of himself,” despite her harping on his “lack of gumption.”

He understands sexism before it became a common concept, noting that his younger sister, Doris, had enough gumption to fulfill her mother’s dreams—and might have “made something of herself” if it weren’t for her obvious “defect” of being a girl. His sharp, well-placed irony is on display throughout the book.

There is so much to recommend in this book, I can’t sing its praises highly enough. If you like humor, history, a good yarn, a fresh voice, and all that a memoir should be, read this book.

In the peripheries of my mind for about fifteen years, I’ve intended to reach out to Mr. Baker, to tell him how meaningful his memoir Growing Up has been to me, both as an aspiring memoirist and as the niece of my Uncle Ebner. I let life get in the way, and never wrote to him. Now it’s too late. His generation of people, like my parents, in-laws, and all the men who served with my uncle during World War II are nearly completely passed from the scene.

That doesn’t mean they don’t have stories to tell that will captivate you and which are as relevant today (and will always be so) as when they were written.

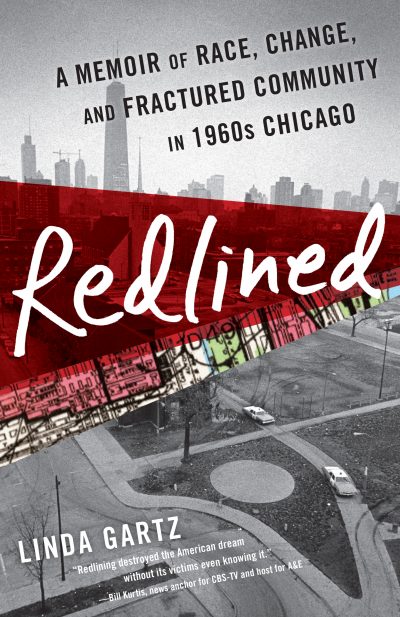

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.