[For an update on what happened to Josef’s colleagues, Johann Rastel and Andrea Lichteneker, see the end of this piece.]

I used that brief moment to step off the train and remained standing there until he went into the other car. I came inside again and laughed from heartfelt joy at my second clever ruse.

Making it successfully across the German border reduced the possibility of Josef being sent back to Transylvania, but more threats to his dream of America still lay ahead.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the United States had pressured European countries to require increasingly stringent medical exams for emigrants before they even boarded a ship to America. A sure-fire way to be left behind was a diagnosis of trachoma, pink eye, highly contagious and, in those days, incurable. Sure enough, the medical exams begin well before getting to the port city of Bremen.

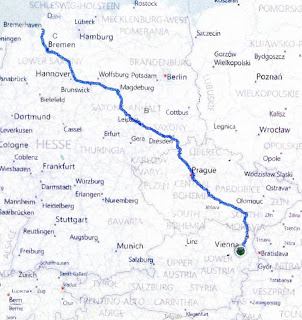

The trip continued to Leipzig where we got out and had a medical examination by an eye specialist. From there we traveled directly to Bremen. We arrived in Bremen on Friday [December 30, 1910] at 9 a.m.

It was from Bremen he wrote the letter to Lisi from which I’ve been quoting portions. How he began that letter and what happened after its completion will be published next week (It was originally published 100 years to the date that he departed, 12/31/1910). He, along with hundreds of others, still had hurdles to jump before boarding the ship to America.

New Year’s Eve in 1910 ushered in a new year with a completely unknown and uncharted future for Josef’s—and therefore, Lisi’s—life.

I have continued to send old family letters (saved by my grandmother) to my Rosetta Stone, Meta, to decipher from the old German. This past April, 2012, Meta determined that an unknown author turned out to be Josef’s sister, Katarina, writing in 1936. She mentions that Johann Rastel asks about Josef, so he was clearly sent back from the train on which Josef had escaped detection by climbing on the roof (see last post). Andreas Lichteneker was sent back too, but he couldn’t send greetings. Katarina reveals he died in World War I–a fate which easily could have befallen Josef had he not kept his wits about him and made his daring move to the top of the train.

I am enjoying Josef’s story yet again. He was a risk-taker. Interesting that he felt he could share his emotions with Lisi, but chose not to in his diary.