In the wake of the George Floyd murder, I was dismayed to see looting again in my former West Side Chicago neighborhood, a grim reminder of the looting and fiery destruction on the West Side after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on April 4, 1968.

Walid Mousa, African Food and Liquor, 4100 block of Madison, after looting. ( Brian Cassella \ Chicago Tribune)

Redlining refused loans to Blacks

My immigrant grandparents had settled near Madison and Pulaski in 1912, worked as janitors, saved obsessively, and eventually bought rental property. My parents purchased their first home on Washington Boulevard in 1949. But buying a house was out-of-reach for most Black families. Redlining, a federal policy, denied loans to Blacks from 1933 to 1968, creating a segregated America.

Redlining, segregation, and COVID-19

That segregation resulted in the health disparities that are allowing Blacks to succumb to the coronavirus at double the rates of White Americans. (Here are articles, videos, and books explaining what redlining is and its still-insidious impact on African Americans today. And here’s a Brookings Institute article: “Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19?”)

When the first Black family moved onto our block in 1963, Whites fled by the thousands. Soon we were one of the last white families in the community. My family continued living at 4222 W. Washington for the next three years, getting to know, and like, our African American neighbors.

In April 1966, we moved five miles north, to Keeler near Montrose, but my parents hadn’t sold their West Side property. Instead they continued to nurture their tenants and three small apartment buildings in West Garfield Park, driving the five miles south whenever in-person help was needed.

Riots/uprisings/protests

King was assassinated two years after we moved. As with the George Floyd murder protests, cities across the country blew up in riots, an explosion of pent-up rage from decades of systemic racism.

A tenant called my mother and warned her not to come into the area. “They’re rollin’ over cars. Mobs of folks are lootin’ the stores on Madison.”

Barbara Lilly, an African American woman who lived in West Garfield Park in 1968, told me years later, “People were burning up houses. . . . At night, you would have thought it was Vietnam.” She added, “They were burnin’ up their own neighborhood, but after King was killed, it was like they lost all hope.”

A devastated landscape

After two days of arson, looting, and destruction, vast swaths of the West Side lay in smoldering ruins. Fifty-two years later, before these latest riots began, my former community still hadn’t recovered.

WBEZ report from West Garfield Park

Now with the recent looting and destruction of small businesses that Chip Mitchell, reported on last week, “In Chicago’s Poorest Areas, Recovery May Be Long, If It Comes At All” — that same sentiment was being expressed.

It’s news that reflects both present-day reality and a reality half-a-century old. The murder of George Floyd is shining new light on a recovery that has been on hold for at least fifty-two years, since Martin Luther King’s assassination.

Looted stores

The looted Dollar store referred to in the story at 4247 W. Madison St., between Keeler and Kildare, is a block away from where I grew up at 4222 W. Washington Blvd. We shopped at many stores on this street, including at the A&P right on the corner of Madison and Keeler, where we dragged our wagon each week to fill with groceries and pull home. That A&P burned down just as the community was undergoing racial change. Arson was suspected.

West Side ignored for half a century

Now food insecurity is a major threat to the livelihoods of the people in my former neighborhood. Mitchell reports, “The pastor of a big church [Reverend Marshall Hatch] a block away from the Family Dollar store said the neighborhood of West Garfield Park never recovered from riots following Martin Luther King’s assassination more than a half-century ago.”

Rev. Marshall Hatch, thanks to Chip Mitchell, WBEZ

A Visit to West Garfield Park, August 2019

That’s right. I saw it for myself just last August, when I was invited to meet with members of Leadership Greater Chicago in West Garfield Park to share my personal historical perspective and show them around my former haunts in the neighborhood.

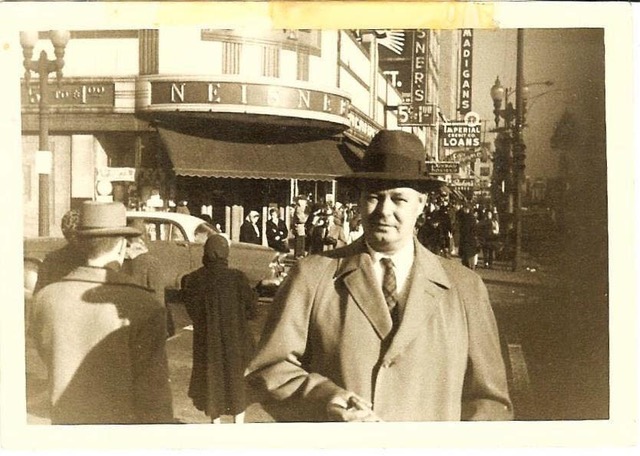

Photo of a friend’s dad, 1950s, a bustling West Madison St. at Karlov looking east.

The once-bustling Pulaski-Madison commercial district was a shabby shell of its former vibrant self. Jobless men hung on street corners. Trash clung to curbs. The city had refused for fifty-two years to invest to help the community climb out of despair.

Refusal to invest as punishment

Mitchell quotes Stacey Sutton, an assistant professor of urban planning at the University of Illinois at Chicago, reflecting the same attitude today: “The reticence from many of our public officials becomes punitive: “‘Well, you destroyed your neighborhood. Therefore we’re not going to reinvest.’”

Rats Dad had to kill at the six-flat, Keeler and Washington, 1967

Throughout the time my parents cared for their West Side buildings, they saw firsthand the total disregard for this community.

I recount in my book, Redlined, how my dad had devised ways to trap and kill rats that actually wore the grass away in paths, with their steady tread through the yard. He captured wild dogs that roamed and terrorized the community, delivering them so often to the Animal Welfare Center, they would say to him, “What! You again?”

On-call April 6, 1968, day after WS riots

But my parents were aging; they could only hold on so long and do the heavy maintenance a six-flat and two 2-flats required: painting porches, fixing furnaces, changing locks of burglarized apartments, and more. (The day after the King riots had scorched more than twenty blocks on Madison St., my parents were right there, around the corner from the devastation, meeting tenants to take care of a furnace problem.)

West Side care after the riots

They never gave up on their little corner of West Garfield Park on Keeler and Washington. My dad, despite having a college degree, had been involved in West Side top-quality building maintenance for more sixty years (he helped his janitor dad when he was a kid in the 1920s).

4222 W. Washington Blvd., my family’s West Side home

He was nearly sixty-nine and Mom was sixty-five when they half-sold/half-donated two of their three buildings to Bethel New Life, which then converted them into low-income housing. Mom still managed the care of my childhood home at 4222 Washington until she died in 1994.

Waiting for investment for three generations

Reverend Hatch told Chip Mitchell of WBEZ, that society needs to “start seeing people in these communities as worthy of investment, just like we see everybody else.”

Let’s hope that Mayor Lightfoot makes good on her promise to help these looted stores get on their feet again, to see the West Side (and South Side) as worthy of investment, and to finally bring hope to a community that’s waited through three generations for change.

Readers: After the terrible looting on the West Side, consider donating food and helping clean up. Learn more here:

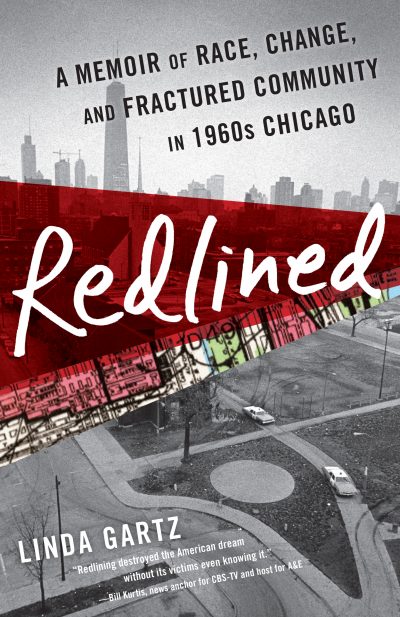

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

Yes am from this Neighborhood my family left in 1969 we moved to Rockford Illinois but I still have family members in Chicago but not this Neighborhood they were just starting to put new stores and business back in this area prayers for my home town am African-American I could never figure out what was happening behind the scenes kudos to you for putting out your new book and I look forward to reading it thank you Linda

Thank you for reading and commenting, Annie. I couldn’t figure it out either. It was only after I started doing research into racially changing neighborhoods that I put it together. A federal government policy, enforced by the FHA, refused loans to Black people. If you like the book, I’d be so grateful if you’d write a review on Amazon. Any length counts – even a couple sentences. Thanks so very much!

I don’t know why this surprises me and makes me more sad than I thought I would be, but I somehow must have convinced myself that the days of “looting” were so far in the past, a phenomenon now only to be associated with foreign unstable countries, or an anachronistic word. Apparently, not so. It also struck me as parallel to the 60s that this the owner of this store was, it would seem, not a descendant of African-American slaves as most of his neighbors surely are. Reminds me of the oddity that business owners in the early 60s was… Read more »

Hi Daniel, I think that people of other backgrounds may have more access to credit and also see an opportunity for a business in underserved areas like the West and South sides. People may be afraid to locate a business there, especially after events like the recent looting, which was terrible. Perhaps it’s because communities on the West and South Side have cheaper rent and are in need of stores, so these entrepreneurs, trying to make it in a new country, are willing to locate there. I’m no expert in this area, but that’s a possible reason. Thanks for reading… Read more »

Hi Linda: I thought of you and your book during the riots of the other week. I grew up in east Humboldt Park – Augusta & California. Memories came back from 1968 standing outside at night and seeing the glow to the south as the West Side burned. Not much has changed in 50 years. Few lessons were learned. I’d like to think that things will be better this time. I have my doubts. I often hear how there’s been disinvestment in the West Side. And that’s true. But who will invest tomorrow when the few current investors have been… Read more »

Hi Andrew, It seems my first reply disappeared from here. I think as long as there are oppressed people, there are going to be upheavals, uprisings, riots, whatever they’re called. I just hate to see the people who just love chaos (with no particular agenda other than creating chaos) infiltrating so many peaceful protests. The city council approved $95 million last year to build a police academy in West Garfield Park! No money to help the community, but this lavish spending on police. I’ll be interested to see what happens next – after these protest. I agree, and have heard… Read more »

I too grew up in Garfield Park on Walnut St. by the Conservatory. We did our shopping on W. Madison St.and there wss the bank, doctor and dentist etc. We moved to Forest Park in 1950 but my Immagrant grandparents lived in the greystone two-flat until 1959 when they both passed away in 1959.I have a 1950 Garfield Park Baptist Church Directory that contains ads all from the Madison Street area in the book. Many good and sad memories. Mine are of happy days and a vibrant shopping area. Iwatched In horror the fires and devastation in 1968. And now… Read more »

Hi Muriel, What a fascinating treasure you have in that 1950 directory. That’s just the era that my parents had bought their first home in WGP. West Madison was like small town: everything anyone could need was within walking distance of the community. It was horrible to watch those fires rage in 1968. More than 200 cities across the country had riots of enraged people whose great Hope (in ML King) was gone. What I found heartening this time was the number of people who came out after the looting and helped clean up. Also, in the age of the… Read more »

Linda, I have read your book “Redlined”and was appalled that this was actually government policy. Thank you for bringing this subject to life with your own personal story. My father’s people came from Rogers Park and Lakeview, My mother’s from Englewood and from the town of Lake before it was annexed. I certainly hope that Mayor Lightfoot will not forget about the neighborhoods affected both now and 52 years ago. I have encouraged my daughter to read your book so she is aware of the back ground of her Chicago roots. Thank you Linda

Dear Tom, Thank you so much for reading “Redlined” and for your comments here. You’re not alone in being unaware of the federal government policy that created such wide-spread segregation. I hadn’t been aware until I started researching. Most people I talk with, especially younger people, are unaware of redlining (or even the word). With this latest flare-up and protests, more and more people are becoming aware of the systemic ways out country has kept African Americans down. I’m especially grateful you gave the book to your daughter to read. So many more young people need to know about this… Read more »

Dear Thomas, Thank you so much for your reply. For some reason I was somehow uninformed about the replies to my Juneteenth post. I’m so glad that you read “Redlined” and discovered this heinous government policy. If you want to see some original (digitized) redlining maps, along with the the racist language that accompanied them, go to the site: mapping inequality.com. I agree with you on our hopes for Mayor Lightfoot. Thanks a million for recommending the book to your daughter. I think this is actually a very important book for young people, and has many themes, from the coming-of-age… Read more »