Aloisia (Louise) Woschkeruscha, wearing her masterpiece, 1912

Celebrating Women’s history month, I’d like to introduce you to an extraordinarily artistic and talented woman: my mother’s mother, Alöisia Koroschetz, née Woschkeruscha (VAUSH-ker-UZH-uh). (She was nicknamed Luisa in Austria, Louise, in America. My mom and I both share the same middle name, after my maternal grandmother).

Sneak preview / “spoiler alert”

Later in life, Louise developed serious mental illness and became a toxic presence in my parents’ marriage. She moved in with them ten months after they married and lived with them for another fifteen years. It was an era with little help or understanding of mental illness.

Behind-the-scenes backstory—not in Redlined:

Therese Müller, later Woschkeruscha, Aloisia’s (Louise’s) mother.

The early part of Louise’s life was promising. She was born May 4, 1886, in Wiener-Neudorf, Austria, south of Vienna, to Johann and Therese Woschkeruscha. We don’t know much about Johann’s forefather’s, but Therese was the daughter of Anna and Paul Müller (Miller). Paul’s surname was also his profession. He owned and operated a successful flour mill.

Anna and Paul Müller, Louise’s grandparents.

From family lore, I learned that as a young child, Louise and her sister had contracted smallpox. The story was that Louise’s father ran through the night to get a doctor when his little girls were burning up with fever.

Louise’s little sister died. Louise lived, but her face had been disfigured with pock scars, making her self-conscious of her appearance for the rest of her life. While her photos show a dramatically good-looking young woman, we can’t see the pits that made her feel she was ugly.

Louise’s “sampler,” created when she was eleven years old.

Later in life, she felt compelled to have acid applied to her face to smooth out her ravaged skin. But it couldn’t smooth out her psyche. My mom said she was convinced no man would ever fall in love with her because of the scars, and that insecurity may have influenced Louise to pursue a career, in which her artistic skills were on display.

She was “a graduated dressmaker from Vienna,” a mantra she repeated over and over to my mother, Lillian, and which Mom, in turn, repeated to us children. In an era when virtually every girl was required to learn all manner of needlework, there’s no doubt that Louise had exceptional talent.

Among our family documents is her Lehrbrief, which translates to “Apprentice Certificate,” proof that she had completed her apprenticeship on July 1, 1906. She’d begun her course of study three years earlier, but had six more years of study ahead, a total of nine years to become a professional in her field.

Louise’s “Lehrbrief,” Apprentice Certificate

The certificate comes from the “Association of Clothing Manufacturers in Baden near Vienna” declaring “Alöisia” “competent to make women’s clothing,” and praising her as “true, industrious, and morally upright.” It’s dated July 1, 1909, and the Lehrbrief is a work of art in itself. As we move around the document, all sorts of cool details emerge.

At the left of the document are symbols of the dressmaking profession: scissors, thread, and an iron. Near the top are a thimble and needle. My favorite is in the upper right. As we zoom in we can see a drawing of a naked man and woman in a large wooden tub–a seeming precursor to the hot tub!

At the left of the document are symbols of the dressmaking profession: scissors, thread, and an iron. Near the top are a thimble and needle. My favorite is in the upper right. As we zoom in we can see a drawing of a naked man and woman in a large wooden tub–a seeming precursor to the hot tub!

“Hot tub” detail from the upper right corner of the Lehrbrief.

Did someone just slip that in as a joke or does it symbolize the importance of the dressmaker to keep the public decent? Check out the photographic details in the photo at right.

Louise had to complete a “Master Work.” The photo at the top is Louise posing in the dress she designed and created to earn her degree.

The photo is dated 1912, so nine years had passed from the time she began her studies to the date of this photo. It may be hard to see the detail on this blog post, but the dress is stunning. The skirt is  splashed with pearls, small satin bows run vertically down the chest, and tiny rosettes edge the high collar.

splashed with pearls, small satin bows run vertically down the chest, and tiny rosettes edge the high collar.

It had always rankled my grandmother that she walked away with only second prize, knowing her creation was the finest in the class. Of course, the mayor’s daughter had to take first.

Maybe that kind of favoritism made her decide she’d be better off finding work across the ocean–because a year after her “master piece” picture was taken, in 1913, she wrote a letter back home to her dress-making teacher, named on the above Lehrbrief–Frau Vogel, about her new job in America. She had set out to make it on her own.

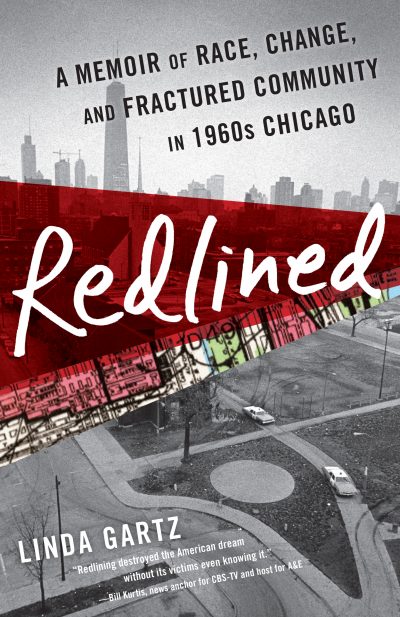

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.