Amendola Airbase; Adriatic in background

After arriving overseas, Ebner was allowed to tell his family only that he was stationed in Italy. It wasn’t until I discovered the Second Bomb Group website (in 2009) that I found out exactly where he was in Italy, the missions on which he had flown, and the crew members with him on each mission. He was stationed in Amendola, Italy, on the Adriatic, just east of the town of Foggia. The above image gives an aerial view of the Amendola Airbase, the Adriatic Sea in the background.

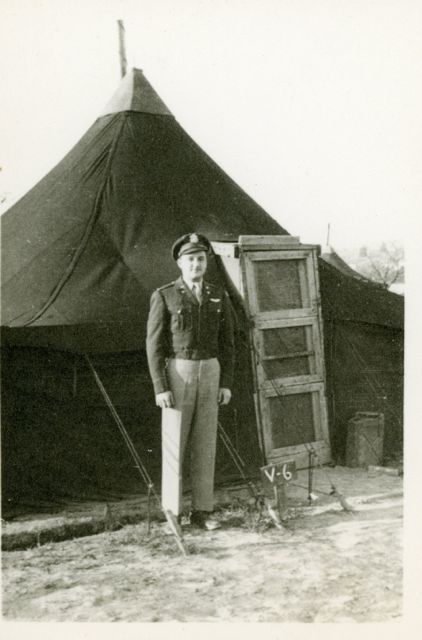

Ebner outside his Amendola tent

Below is the narrative of what happened to Ebner after flying overseas and beginning combat. When you get to the end of the post, you’ll understand the significance of posting on this date, October 12, 2015.

A thunderous sky shot bullets of rain, forcing the American airmen to land in North Africa just before Christmas 1944. My uncle, Frank Ebner Gartz, was among the young aviators destined for Europe to begin bombing missions.

All in their late teens or early twenties, the young men were eager to seize upon any high jinks they could muster from this welcome delay. Officers warned them that Marrakech was off limits, but the newly minted fly-boys, pulsing with youthful spirit and bravado, ignored their commanders and poked into the city’s every cranny and casbah. Ebner, as the family called him, wrote his brother and sister-in-law, my parents, about his adventure: “It was the start of a two-week vacation in which all we did was eat, sleep, haul wood and coal for our fire and play cards, raise hell, get drunk, and have a hell of a good time.”

During the previous year, Ebner had been fired in the crucible of navigator training with the U.S. Army Air Corps in Hondo, Texas, where daunting coursework, grueling tests of physical endurance, and the specter of “washing out” haunted the young cadets. Failure to measure up meant a sure ticket to the infantry. Having beaten the odds and graduated as a navigator, Ebner was about to face combat in flak-ripped skies. A little hell-raising seemed in order.

But when writing to his parents, my grandparents, he penned a far more subdued version of how he had spent his layover in Morocco.

January 2, 1945

Hello Folks,

I’m still waiting for something to happen. We celebrated New Year’s here, but it’s not like the way we used to do it. I thought back to the times we used to pour lead into water to see what our fortune would be for the New Year.

“Pouring lead” was a favorite New Year’s Eve tradition my immigrant grandparents had brought from Transylvania and passed on to the family. We melted a chunk of lead in an old pot on the stove and then, with a flick of the wrist, dumped about a tablespoon of the molten metal into a bowl of water. Bubbling furiously, the cold liquid instantly solidified the lead into fantastical shapes. Like analyzing a three-dimensional Rorschach, we teased meaning out of each unique form to predict what the upcoming year held in store for us. Did that hardened chunk look like a boat? Perhaps travel was in our future. A tiny shoe? A new baby might join the family.

Ebner had celebrated his wartime New Year’s Eve with eight fellow crewmembers, drinking brandy, sweet wine, and a gallon of tomato juice while playing a “nice quiet game of blackjack.” Even if he had followed the family tradition at the dawn of 1945, no one’s wildest imagination could have predicted his fate.

*****

Ebner joined the 15th Air Force, 2nd Bomb Group, stationed at the Amendola Air Base on the Adriatic Sea, just inside the spur of Italy’s boot. From that key location, America’s B-17 heavy bombers could target enemy munitions factories, railroad yards, oil refineries, and aircraft production facilities from Austria to Bulgaria. Bristling with machine guns, the B-17 carried a crew of ten, positioned from the tail to the plexiglas nose, an enormous half sphere with a 180 degree view of sky and earth. Within this giant “fishbowl” sat the bombardier, ready to call out “Bombs away!” before dropping the payload. Positioned right behind him, my uncle sat at the navigator’s table, where he crunched the numbers to direct the plane to its destination—and back home again.

B-17s returning to Amendola Airbase after completing a mission.

When enemy fighters zeroed in on the bomber, these two crewmen had the clearest view of those planes swooping under, around, and above them, ferociously unloading continuous bursts of machine gun power. Every B-17 crewmember jumped to his own automatic weapon, returning fire, measure for measure. But they were helpless against the German anti-aircraft guns shooting from the ground, spewing flak in thousands of rounds, making the air was so thick with rapier-sharp black shards, it looked to the crewmen like a carpet they could walk on.

B-17 surrounded by Flak. Seated in the plexiglas nose, the navigator and bombardier had a 180º view of the ordnance exploding around them.

On January 20, 1945, Ebner was assigned his first mission—to bomb the oil storage facility at Regensburg in southern Germany. He would go through the same pre-mission routine twenty-five times during the next three and a half months. In the early morning hours the sergeant called his name, along with those of the pilot, co-pilot, and bombardier. “Gartz, Atkinson, Berryhill, Van Nort.” I can imagine the pumping adrenaline; my uncle’s straw-lined throat as he forced down his fear along with the daily breakfast of green powdered eggs and fried Spam.

All of the young men would have tried to appear confident when they met together in the cool, damp darkness of the briefing room, a cave previously used to store wine, to learn about their assigned target. Of major German strategic interest, Regensburg would be heavily defended, and flak would be intense.

At 08:40, twenty-eight B-17s lined up nose to tail on makeshift runways, each plane carrying a typical load: 3000 gallons of fuel, three to four tons of bombs, and hundreds of pounds of ammunition. Any spark from an errant engine failure would end in conflagration. Within seconds of each other, the planes took off, then formed a tight formation over the Adriatic Sea, only fifty feet separating the wing tips of each.

After two years of intense, rigorous training, Ebner was now put to the test in real combat. All told, the B-17s dropped five hundred fifty-one 100-pound bombs that day on the target. Ebner’s plane returned from the mission unscathed, but one B-17, with all ten of its crew members, had been lost.

B-17 dropping bombs on an enemy target

After his February 13th mission, bombing a Vienna ordnance depot, Ebner wrote home about the ordeal: “It was super hell. We had 42 flak holes in the ship but no one was hurt.” Others were not so lucky. On another plane flying that day, one airman was killed and one wounded.

On Ebner’s fifth mission, he joined forty-one other B-17s to bomb Italy’s Verona/Perona Railroad Bridge. The navigator on one of these planes continued to call headings after flak tore off his leg eight inches below the crotch. Thinking fast, the bombardier tied a tourniquet around the bleeding stump, saving his buddy’s life.

Two weeks later, Ebner wrote about his March 16th mission to my grandfather:

It was the hottest thing I have seen so far…more and bigger flak. My bombardier sits up in that plexiglas nose where he can see all that stuff exploding around him. It sort of gets on his nerves. I was trying to explain to him that when your time comes it doesn’t matter where you are…your number is up, and that’s all there is to it.

Twenty-year-old Ebner had seen what befell his fellow airmen: ripped-off limbs, spiraling down within flaming planes, plunging into the Adriatic, or crashing onto enemy territory. It’s little wonder he adopted a philosophy that allowed him to focus on function rather than fear. To my parents, he explained it this way:

When my turn comes I’ll get it no matter how much protection I wear, and if the good Lord has some other way [for me] to die, I’m not going to get it on a battlefield. Some people call it fatalism, and perhaps it is, but it’s a good way to feel about it.

His mother had other ideas. An ethnic German from what is now Romania, she was his most devoted correspondent, struggling to express in tortured syntax and spelling what was in her mind and heart. Petrified of the dangers her youngest son faced, she coped the only way she could—through fervent, daily prayer.

My Dear Ebner,

I do more and more praying for you that our God is with you always and bless you and save you and bring you bak to us. Your lovly thoughtful letter is so very good medizin for my very tired heart and mind. Is the best docter could give. I am so very glad you have so much good Luck in your Mission. God answer my praying.

Frank Ebner Gartz. Jan. 1942 Austin H.S. Grad Photo used in shrine

Right after he was drafted, my grandmother created a shrine of sorts to Ebner. Flanked by two green-beaded lights and set upon a 1930’s console radio, his high school graduation picture was bathed in a perpetual eerie lime glow. First thing every morning, she and Grandpa paused before his photo to say, “Goot morning Ebner,” and last thing before going to bed, “Goot night, Ebner.” During the day, she spoke to the photo. “I feel as if I talk to you,” she wrote him. “Is goot for my soul.” In many letters, she reassured her youngest son, “Every day I be praying by your pictur at the green light.” She believed God had answered her prayers.

After March 23rd, Ebner flew twelve more sorties to Czechoslovakia, Austria, Yugoslavia, and Italy, for a total of twenty-five from January to May. On all the missions Ebner flew, only six B-17s were lost. On the missions he didn’t fly in that same time period, twenty-one planes were lost—more than three times as many. “Fly with Frank,” could have made a good motto. He truly seemed blessed.

On May 8, 1945, the Allies declared the war officially won and named it “Victory over Europe” or VE Day. Overjoyed, the Gartz family couldn’t wait to greet their darling Ebner back in Chicago, safe and whole. He was promoted to first lieutenant on May tenth, just four days before his twenty-first birthday.

*****

With the threat of imminent death behind him, Ebner could think more clearly about his future. He’d written all along of his intention to marry Cookie, his high school sweetheart, whom my grandmother adored. In one letter, his mother had written: “Ebner, you know that I like nothing better as you with Cooky [sic] to share the life together.”

Cookie and Frank at his Austin H.S. prom

Pressure from both his mother and Cookie to determine his postwar future was mounting. Cookie insisted he reassure his mother “immediately if not sooner” that he intended to go back to college upon returning to Chicago. “I don’t want your mother to think that I’m standing in your way.”

I wonder if that was a noose he felt tightening? He had faced death with aplomb, lived as a man among men, and now he had to go back to school?—Because his mother and girlfriend said so? They seemed to expect him to flip a switch in his brain. Turn off the cool-headed, focused navigator who had directed his B-17 and its crew through explosions of flak and fire. Turn on the college student, the dutiful son, the willing bridegroom, and leap right back into his former, narrowly circumscribed life. A mounting ambivalence crept into his letters. To my parents:

Right now I’m very confused as to what I’m going to do in the post war era. I want and don’t want to go to school. I want and don’t want to get married. So I really don’t know what I want to do.

He found a way out of his dilemma in June 1945, when he scored a coveted job with the 15th Air Force Headquarters in Caserta, Italy, just north of Naples. Arriving in droves to develop plans for rebuilding war-ravaged countries, American VIPs needed a crack navigator and pilot team to fly them to their appointments throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity—good salary, extra flight pay, and the chance to rub shoulders with congressmen, senators, special envoys, ambassadors, and high-ranking generals. Ebner wrote to my Dad:

Take in your welcoming mat, as your little brother is remaining in the Mediterranean Theater as long as he can. The thing that might do me some good is getting to know some of these wheels for future reference. The army is finally paying off for the times I flew over Vienna on a carpet of flak.

It was also the perfect excuse to put off those nagging maternal expectations for marriage and school. I can imagine the disappointment back in Chicago. Like a pricked balloon, the family’s anticipation for a joyous homecoming sighed out into a crumpled melancholy acceptance. But the war was over. Everyone could stop worrying.

The job turned out to be everything Ebner had hoped for. He wrote to a friend on July 16th:

I’ve been having a swell time since I’ve been with this outfit and have seen quite a bit in my young age. My first trip was a Lu-Lu. I virtually had a tour of the Mediterranean. We left here one morning and crossed the boot and flew to Athens, Greece, where I had an inexpensive dinner of octopus for only $54.00. I bought dinner for 9 that night and it was well spent. From there we went to the Holy Land and saw Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The next day we flew to Cairo. On the 5th of July we had a 13-hour flight from Cairo to Casablanca and boy, that was tiring as hell. We slept in Casa that night and flew back to Italy in the morning through a thunderstorm.

During the summer of 1945, Ebner piled on the adventures. He flew to London twice, Egypt, Bucharest, Tel Aviv, and the French Riviera where, he noted, “the girls wear 4 patches and call it a bathing suit!” He toured Venice in a gondola, swam in Northern Italy’s Lake Garda, joined a group of war correspondents in Florence, and spent the night in Salzburg where he drove some “beautiful cars,” the spoils of war.

Ebner in Egypt, summer 1945

Such a life had been beyond his ken, having grown up in an isolated Chicago neighborhood where he had dated only one sweetheart, whom everyone presumed he would marry. For the first time, he was exposed to the world. Handsome, good-humored, sweet, and scampish, Ebner discovered girls everywhere found him irresistible.

Cookie is going to be the blushing bride some day, but I found out I can live without her for a while and really live… I’m finding how much sport it is just running around breaking a few hearts and raising just a little general hell. I know enough to realize the responsibility of married life.

July 21st to his friend:

If I stay over much longer, I’ll be putting off the wedding for quite some time. At least for the duration when I’ll have had enough time to sow all my wild oats and brother, I’m getting rid of plenty over here.

He met an American woman working for the U.S. Embassy in Frankfurt, which had been virtually leveled by the Allies just five months earlier. He wrote:

August 15, 1945

Wow! What a time we had in Frankfurt. It’s quite bombed out and my hotel room was in much better shape than hers, and being gallant…ahem! Need I say any more?

Marriage was looking ever less appealing. He wrote to my dad on August 18th: “I’ve made up my mind on the subject of getting married immediately upon my return. It’s going to be postponed. As far as I’m concerned, I can live without it. I’m beginning to wake up.”

As his tour of duty wound down, he stayed on in Europe, hoping to get permission from the Soviets to visit his maternal grandfather in Romania. “After I see Granddad,” he wrote his parents in mid-August, “I’ll be ready to come home. I passed up another chance [to fly home] 3 days ago, but another will come along.”

When the family hadn’t heard from Ebner for several weeks, everyone assumed his busy flying schedule precluded time to write. Then a letter arrived at my grandparents’ home on October 17th, ten days after it was written, from Captain Uhler, chaplain at the 300th Hospital in Naples. It stopped my grandmother’s heart. She read it again. Then again. She called my parents, choking on the words as she read the letter to them.

Dear Mrs. Gartz:

The Hospital Command regrets to inform you that your son, 1st Lt. Frank E. Gartz…,who was admitted to this hospital October 5, is now considered to be seriously ill. Frank is in the early stages of Infantile Paralysis [polio infecting the spinal cord], and it is impossible at this time to say what the outcome will be.

In a panic my mother, father, uncle, and grandmother sent out a flurry of letters to Ebner. From my mom:

What did they do to you, Darling? When we didn’t hear from you for about four weeks, we were wondering what happened, but as long as the war is over, frankly didn’t think there was anything to worry about. Who would have dreamed that you might get sick!!

From Ebner’s mother:

The letter from Capt. Uhler came to us like a bomb—that this couldn’t happen to you.

No one could have prayed harder, more fervently, more faithfully for her son’s safety than my grandmother had for Ebner. “Trust in God,” she wrote him over and over.

My father was especially close to Ebner. Ten years older, Dad had changed his kid brother’s diapers and taken him to the play in the park when their mother was overloaded with work. When the young navigator was about to ship overseas in December, 1944, Dad had written his brother a heartfelt farewell letter:

There is so much pent up within me that I want to say to you and I don’t know how to get it out. You leaving us — not to see you for probably a long time. Our love for each other is truly without bounds. To me you are somewhat more than just a brother. I saw in you all the things I wanted to be and do.

After receiving the news of Ebner’s illness, Dad sent along poems and family photos. Everyone added homey tidbits of news to cheer up the patient, but a gut-wrenching undercurrent of frantic worry crackles beneath each letter’s encouraging tone. From Dad:

I can’t tell you how hard the news has hit us all….We all pray for you, Sonny, every day at every occasion, for you to pull through and pull through o.k.

A few weeks later, all these letters, with their warm “Get Well” wishes and light-hearted anecdotes, arrived back in the family mailboxes. On the front of each envelope: a gut-punching, bold red stamp: DECEASED.

Ebner’s commanding officer, Major David T. Perkins wrote to my grandparents in a letter dated October 18, 1945, six days after Ebner had died at 10:15 p.m., October 12, 1945. It revealed a sickening reality: Ebner had been dead five days before anyone at home even knew he was ill.

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Gartz:

Your son, Lt. Frank E. Gartz served with us as this base for over four months….I wish to express our deepest sympathy and condolence. He was popular among his fellow officers and enlisted men and was a credit to you, to us, and to his country, which he served so well.

*****

My father died in 1989; my mother in 1994. After Mom’s death, as I searched the dusty corners of my parents’ attic, separating trash from treasure, I discovered the trove of more than 200 World War II missives the family had saved for half a century. The letters introduced me to the delightful, at-times rascally, warm-hearted, and loving uncle I had never met, but now miss terribly.

The first letter I found in the collection was a carbon copy of a letter my father wrote to Miss Hartley, Ebner’s division teacher from Austin High School, who kept up a regular correspondence with many of her former students in the service. I sat down on a trunk in the attic’s dim light, pausing from my post-death sorting duties. Reading that letter, I was swept back to my family’s moment of loss and wept at my dad’s raw, lyrical grief.

November 2, 1945

My Dear Miss Hartley,

It is with a very heavy heart that I write you our Frank is gone. Yes, gone for good and we will never see him again in this world….We can hardly believe it, just not seeing him again. We had planned so many things with him….Dad and Mother are all broken up. Dad keeps saying, “Our pride, our all—gone.”

*****

More than 400,000 Americans died in World War II, each family wracked with pain—a son, brother, husband—never to be seen again. It was just the utter irony of Ebner’s death that lives with me today. After facing the full defensive power of enemy fighter planes and anti-aircraft machine guns, he was brought down by the stealth of a deadly virus, well after the fighting was over. I was left wondering at his fate—one that he was prepared to accept with equanimity, as he had told my father. …and if the good Lord has some other way [for me] to die, I’m not going to get it on the battlefield.

Dad lost his best friend. Mom lost her favorite brother-in-law. My grandparents were awash in grief. About a month after the letter arrived with the news of Ebner’s death, my mother discovered she was pregnant with my parents’ first child, conceived within days of her brother-in-law’s passing. Responding to the usually joyful news of a first grandchild, my grandmother said, “Don’t have children. They’ll only be used as cannon fodder.”

My grandparents lived a mere half block from us, yet we seldom saw them except for birthdays and major holidays. The warm, tender, prayerful mother I discovered in my grandmother’s letters to Ebner was unrecognizable to me. I knew only the distant, cold, and judgmental woman who seemed to have little interest in her grandchildren and actively disliked my mother. Adored by all, Ebner was the one person who could have brought us all together.

It is impossible to say how the future might have differed had Ebner lived, but his death, like a stone to everyone’s hearts, rippled to the edges of our lives in ways no molten lead could have augured.

The End

Frank Ebner Gartz. May 14, 1924–October 12, 1945

In the shrine my grandmother had created when Ebner was in the service, she replaced his high school graduation photo with the one above: Ebner dressed in his full second lieutenant’s uniform. It’s the one I always remember at the entry-way to her home, flanked by the two green lights, each topped with a miniature airplane, all set atop a 1930’s console radio.

Thank you for reading. My hope is that the letters and photos I’ve posted on this blog have given insight into the story of one young man’s experiences in training for and fighting in World War II, and the love and support that millions of families gave to their soldiers and airmen. You can find all the previous letters back to April, 2013 in the archives of this ChicagoNow blog. Letters prior to that, and the start of the blog recalling when Ebner reported to the draft board on January 23, 1943, are posted here: “A World War II Draftee—70 Years Ago”

This next week I will attend what is likely to be the last Second Bomb Group Reunion in Shreveport, LA. So many of the young men with whom Ebner fought have either died or are too incapacitated to travel (Ebner would have turned 91 this past May), that there simply are not enough of these brave airmen to continue the reunions. The website will, however remain active.

If interested, you can search for Ebner’s missions by going to the 2nd Bomb Group website; Click on “Database” in the left column. Click on “2nd Personnel.” In the box “Inquiry by crew member” type: Gartz*—Don’t forget the asterisk. All Frank Ebner’s missions and crew members will pop up.

It’s a fascinating, historic site all around, so if you’re into World War II history, you’ll really relish all the information and personal stories you can find here. Thank you to our wonderful webmaster, Sid Underwood.