I wanted to find a way to connect this week’s blog post with last weekend’s display of hateful bigotry: white supremacists protesting changing the name of “Lee Park,” (for the Confederate general, Robert E. Lee) in Charlottesville, Virginia.

White nationalists arrive at Lee Park, Charlottesville, VA [AP photo by Steve Helber]

Even if only the most racist of Americans would actually mouth those words today, back in the 1950s and 1960s, whites spoke openly against blacks entering their communities–and thought they had good reason.

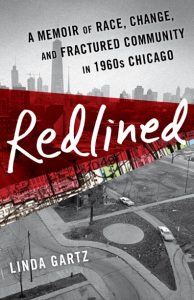

Today’s post will look back upon a time in our family’s history when entrenched racist laws and policies stuffed blacks into segregated neighborhoods and froze blacks out of the housing market. Here’s a shortened version, a “sneak preview” of how a portion of that era plays out in my book, Redlined: A Memoir of Race, Change, and Fractured Community in 1960s Chicago.

From Chapters 9 and 11

Like most major American cities in twentieth century America, Chicago was rigidly segregated. African Americans were clustered primarily in Chicago’s Near West Side and in the South Side’s “Black Belt,” a strip of land that stretched from about 28th Street to 70th in 1940 and inexorably expanded as blacks flocked to the city.

African American family arriving in the North from the South

Chicago’s black population had been burgeoning ever since the beginning of the Great Migration, when vast numbers of southern blacks moved to northern cities and California, starting near the end of World War I and gaining steam in a second wave after World War II.

In the 1940s and 1950s, three million blacks fled north from the daily degradations and abuses of the Jim Crow South. Hundreds of thousands headed to Chicago, where the black population nearly tripled from nearly 278,000 in 1940 to more than 812,600 in 1960.

Like my parents, many, if not most whites, remained unaware that this massive population shift was underway—or the reasons behind it. They just knew they didn’t want African Americans moving into their white neighborhoods.

In July 1953, a black couple purchased a home in all-white South Deering, on Chicago’s South Side. For months, white crowds protested and rioted, hurling bricks, shooting off pistols, attacking and injuring black passers-by. One of the picketers proclaimed to a CBS reporter that she didn’t want blacks in her community because “…every place they’ve taken over, they’ve turned into a slum.”

Whites were certain blacks would destroy their communities–and alongside that, would destroy whites’ greatest investment: the value of their homes. In her epic book about The Great Migration, Isabel Wilkerson writes:

It was an article of faith among many people in Chicago and other big cities that the arrival of colored people in an all-white neighborhood automatically lowered property values, That economic fear was helping propel the violent defense of white neighborhoods.

The fears were not unfounded, but often not for the reason white residents were led to believe.

My parents, and probably most whites at the time, were unaware of how our government intentionally segregated America by using color-coded maps (Green, blue, yellow, red) to rate communities as to which were a good risk for banks to lend mortgages.

Green: good housing stock. A safe place to lend.

Blue: still worthy of a mortgage.

Yellow: housing stock was beginning to be run down.

Red: dangerous to lend! A community colored red meant no mortgages were available for anyone. Just one black resident in an area (or sometimes even the “threat of Negro encroachment,”) prompted “redlining.”

With the arrival of a “Negro family,” whites feared losing their greatest investment: their homes. Many defended their territory with terror and violence. (See details in my post “Threatened with Negro Encroachment“).

On August 1, 1959, four years before the first black family moved onto our block, a house deeper into West Garfield Park than blacks had lived prior was sold to an African American family—on Jackson Boulevard, a couple blocks south and west of our home.

A burning piano, purchased by a WWII black vet for his daughter; destroyed with all family’s belongings by rioting whites in Cicero, Il [Chicago Tribune Archives]

end book excerpt

People of good will had hoped these kinds of terrorist attacks against African Americans were behind us. Sure, race relations have remained fraught, and the white race and black race still have to work on mutual understanding.

But when I, like millions of Americans, hear hate-filled speech against blacks; see hate-filled, racist violence, I’m disgusted and distraught. White people of good will have to stand up to this bigotry and against those in power who encourage it.

Chicago, and most of America, is still segregated, preventing blacks and whites from really getting to know one another. It wasn’t until my family stayed in our community for several years after the first black family moved onto our block, that we had an opportunity to know African Americans–and were able to dispense with previous stereotypes

Redlined: To be published by She Writes Press: April 3, 2018