In 1910, Eastern Europeans overall were inflamed with a passion to immigrate to America, where, some truly believed, the streets were literally paved with gold! (Seventy percent of immigrants to the United States around that time were from Eastern Europe).

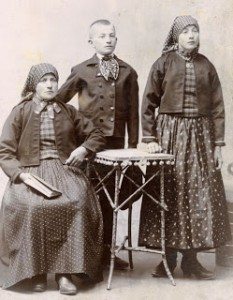

My grandfather, Josef, center, with his mother and sister, both named Katarina, the family he left behind. Undated. How old does Josef look to you (born 1889)?

My grandfather, Josef Gärtz was among those who caught the spark, and he began saving for his trip to “The Promised Land” when he was fifteen. His decision would change the course of his future-and of course, laid the foundation for my father’s and our family’s lives.

By the time Josef was twenty-one, he felt he had saved enough money to leave his home and family. I’d always known my grandfather was often impatient, and apparently was so as a young man. He didn’t want to wait for the long visa process, so he just took off for America before his exit papers were in order. His diary “Meine Reise Nach Amerika” (My Trip to America), and letters to his sweetheart show that he almost didn’t make it.

Christ Saturday (Christmas Eve), December 24, 1910

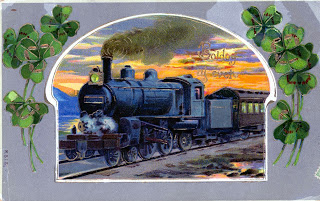

Josef’s plan was to hook up with a third friend, Rastel, in a town called Klein Kopisch, and the three would travel together from there. The first snafu occurred almost immediately. When Josef and Lichtneker arrived in Klein Kopisch, they went to get coffee. Sure enough, as soon as they left the tracks, Rastel’s train pulled in! They jumped up, but by the time they found their friend and gathered their luggage, “the train slipped out right from under our noses, and we had to wait twelve hours for the next one.”

Sunday, Christmas Day, December 25, 1910

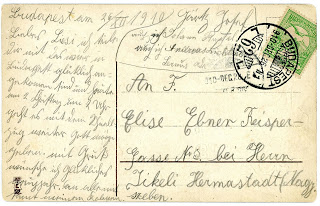

The three friends boarded the noon train to Budapest, about 270 miles away and, based on notes he made on a previous trip, a nineteen hour train ride. When they arrived in Budapest, on December 26th, he sent a postcard to Lisi Ebner (his sweetheart he also left behind, and my future grandmother- but that’s another post), and signed by all his companions as well:<

I’m sharing with you that we have happily arrived in Budapest and today, on the 2nd Christmas Day, we will travel onward with the fast train, God willing. With greetings I wish you a Happy New Year [and] from all my colleagues.

Each signed in his own handwriting, thereby corroborating the friends’ names he had recorded in his diary.

It would be the last time the three young men would be together, for things went downhill before they ever got to Vienna.

In Budapest, they switched to a fast train to Vienna. In those days fifteen to twenty miles per hour was “fast.” Josef urged his friends not to sit together “in case they had to get away quickly, but they didn’t listen,” leading me to believe none of the three had proper papers. Josef followed his own advice and sat in a separate compartment with “two colonels.” He fell asleep on the long train ride, which stopped in Bratislava, on the Austrian border. Josef was shaken awake by a border agent. “I threw him a frightened look, but he asked me in a friendly manner where I was traveling to.”

“And what do you do in Vienna?”

“Work.”

The agent ordered Josef off the train. “I knew what that meant,” he wrote. Thinking fast, he concocted a daring solution. “Sure. No Problem. I just have to fetch my things,” he told the officer.

I left my luggage behind, went out the door, climbed up the ladder, and lay down on top of the car. I cannot thank God enough for sending me this thought. But when the horrid train started to move, the sharp air cut through me so that I thought I would fly away like a piece of paper.

Now picture this: it was December. At best, maybe 25-30 degrees. He would have been battered and buffeted by a frigid windchill for the 37 miles from Bratislava to Vienna. Based on the travel times he had recorded for previous trips, and the train moving at about fifteen miles per hour, that’s two hours he’d have to endure the terror of literally hanging on for dear life, wondering if he’d live to see Vienna, much less America.

“When we arrived in Vienna,” he wrote, “I went back into the train car and was very thankful to our Lord God. But, oh, no! My colleagues had disappeared! They must have been hauled off the train. I stood there crying, but managed to pull together fresh courage. I waited for two days in Vienna, hoping my friends would show up, but it was in vain, and I had to set out further alone.”

Josef Gärtz, Vienna, about 1910. The card on the trunk says “WIEN MARIAHILFE STRASSE,” Vienna, Mariahilfe Street. The background could be a studio “set” or perhaps in the apartment he stayed there.

The photo here of Josef is not dated, but he’s posing with a trunk, on top of which a sign labeled Wien (Vienna) is propped. He is about the right age, so it could be a remembrance of this trip. He was long and lean with an affable nature, ready wit, and another trait his journey reveals: fierce determination.

In Vienna, he boarded a train into Germany, wherein lay his ultimate destination: the port city of Bremen in the northwest of the country. “When I got to the German border, it got a little dicey again. The border officer came into the train car, asking for my passport. Once again, I thought fast. ‘One moment please. My passport is in my suitcase.’” While the agent continued on, checking others’ papers, Josef slipped off the train. “I remained standing outside until [the agent] went into the other car. Then I returned to my seat, and the ordeal was over.”

With the successful crossing of the German border, the threat of being sent back to Transylvania seemed to have passed, but more challenges were still to come.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the United States had pressured European countries to require increasingly stringent medical exams on emigrants before they even boarded a ship to America. A sure-fire way to be left behind was a diagnosis of trachoma, pink eye, incurable – and highly contagious in those days. In Leipzig, he and all others were checked by an eye specialist, and only then permitted to go on to Bremen.

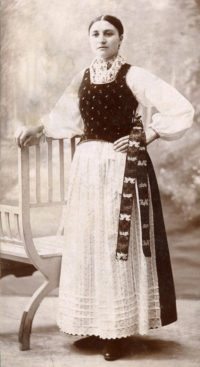

Lisi (Elisabetha) Ebner. On the back she wrote (in German): “To remember me, June 1910.”

On Dec. 30th, six days after leaving Hermannstadt, Josef wrote a letter to his sweetheart, Lisi, back in Transylvania: “Dear Lisi, I want to tell you that I have arrived in Bremen happy and healthy. Tomorrow, on December 31, 1910, we’ll board the ship if we don’t get sick. Every day we are probed by a doctor. So far I am completely healthy.” Others weren’t so lucky. He met several who had languished in Bremen for up to eight weeks because of eye infections or bad health, denied their dream of America.

December 31, 1910

“Early Saturday morning at 4 a.m., we saw a doctor who looked us in the eyes and inoculated our left hands with four shots. At 7 a.m. we took a two-hour train to the ship. We boarded the steamship, Friedrich der Grosse, at 10:30 a.m., and at 11:30 it departed directly for America.

Friedrich der Grosse, the steamship that brought my grandfather to America.

“I was moved by sadness, joy, and fear as the mighty colossus pulled us far out over the waves of the great sea. Everyone on land waved after us with their handkerchiefs as they wanted to share with us a last and friendly farewell. They know such a trip deals with life and death, and we’re never certain if we’ll see each other again.”

Josef truly rang out the old on New Year’s Eve, 1910, departing from everything familiar – and would ring in 1911 with a new life in America.

One hundred seven years later, I see in his daring trip one of the millions of journeys undertaken by immigrants to America and the opportunities they have bequeathed to their children by their bold confidence.

Every American has an immigration story. What’s yours? Please share in comments. I love to hear from my readers.

Note: This is a combination of several separate posts, originally seen on my blog, Family Archaeologist, in 2010. To read the more detailed original posts, each with lots of cool photos, see:

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.

I have enjoyed the stories that you have posted. You are so fortunate to have the legacy of your family history past down to you. Writing a book about all the stories and sharing the book with your family as well as others. It is unfortunate that many stories, places, names, and family members have been lost to time to our families of today. I find it quite interesting to read other peoples journeys and history. Keep up your writing and passing on your stories to us out here.

Hi Sharon, Thanks so much for your comment and again, (I sound like a broken record), I am so sorry for this late reply. Yes, so much of family history has been lost, and I’m so appreciative of comments like yours that you find my journey into the past as one you can relate to. It means a lot to me. Thank you.