On New Year’s Eve, 1910, my grandfather boarded a steamship for America and recorded in letters and diaries his harrowing journey. The story starts with Terror Atop the Train and continues here:

Josef’s “terror atop the train”—two accounts

Josef wrote both in his diary and to his sweetheart, Lisi (my future grandmother), about his terror atop the train from Pressburg (Bratislava) to Vienna, one corroborating the other, but each using slightly different language.

In the diary, he wrote:

I thought the sharp wind would throw me under the fast train like a piece of paper, but I held tight until we were in Austria. Then I came back down into the car and was very happy, but also distressed because my colleagues weren’t there, and it was very much fun to travel as a threesome.

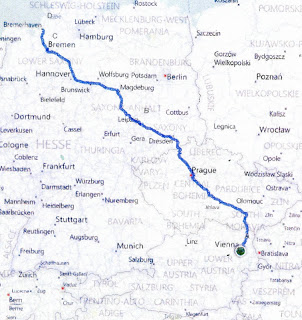

Josef Gärtz’s travels from Vienna, Austro-Hungary to Bremen, Germany

[For an update on what happened to Josef’s colleagues, Johann Rastel and Andrea Lichteneker, see the end of this piece.]

Josef must have arrived in Vienna, late December 26th or early December 27th–

I departed Vienna Wednesday evening [December 28, 1910] at 10 pm. On Thursday [December 29, 1910] at 11:00 am, I arrived at the German border, where it got dicey again. There the border officer asked me how old I was. I answered 24 years [he was only 21]. Then he asked for my passport. I said, ‘Immediately, Sir. My passport is in my suitcase.

U.S. demands stringent medical exams for emigrants

Beginning in the late 19th century, the United States had pressured European countries to require increasingly stringent medical exams for emigrants before they even boarded a ship to America. A sure-fire way to be left behind was a diagnosis of trachoma, pink eye, highly contagious and, in those days, incurable. Sure enough, the medical exams begin well before getting to the port city of Bremen.

Eye exam

The trip continued to Leipzig where we got out and had a medical examination by an eye specialist. From there we traveled directly to Bremen. We arrived in Bremen on Friday [December 30, 1910] at 9 a.m.

It was from Bremen he wrote the letter to Lisi from which I’ve been quoting portions. He, along with hundreds of others, still had hurdles to jump before boarding the ship to America.

New Year’s Eve in 1910 ushered in a new year with a completely unknown and uncharted future for Josef’s—and therefore, Lisi’s (my future grandmother) —life.

Out to sea

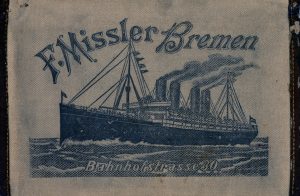

The F. Missler canvas wallet in which my grandparents had saved decades-old letters, now over a century old

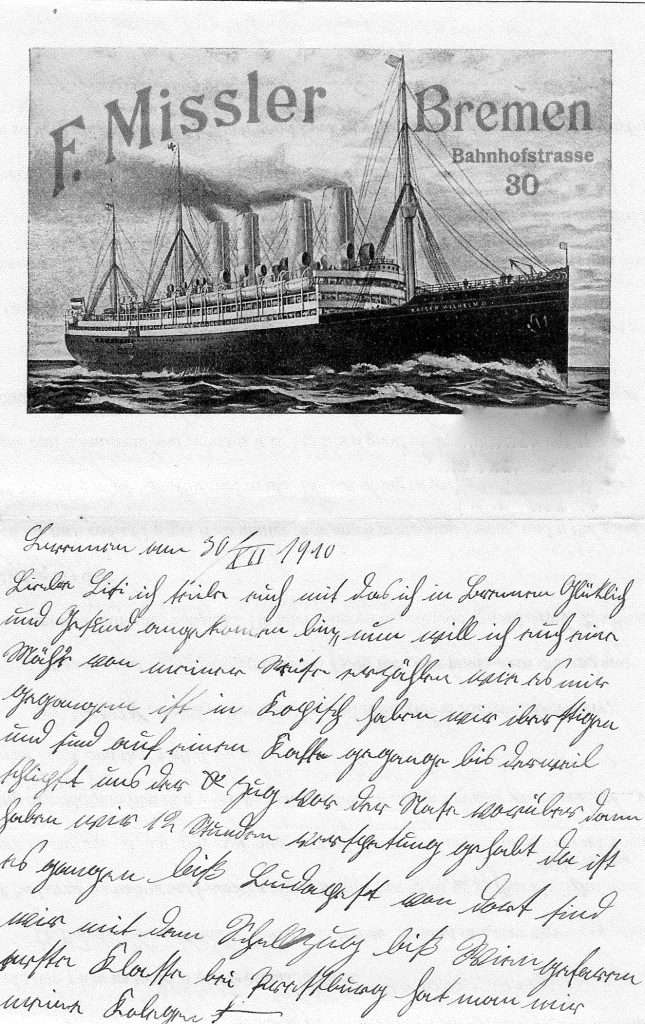

Once Josef arrived in Bremen, and his path to America seemed clear, he wrote to Lisi. Not only had Friedrich Missler, probably Bremen’s most successful ticket agent, given thousands of passengers a brown, canvas wallet like the one in which I found Josef’s diary [see image left], he also provided stationery emblazoned with “F. Missler” and the agency’s address at 30 Bahnhof Strasse [literally: Train Station Street], proving Missler was a marketing wizard of his day. Many descendants who have these wallets have mistakenly thought “Missler” was the name of the ship pictured and researched in vain to find it.

Here’s the first page of Josef’s letter to Lisi, written on Missler stationery. If you look closely, you can see the date at the start of the letter (the date is first and the month follows in Roman Numerals: 30/XII 1910). See below image for transcription.

At this point Josef describes his misadventures and narrow escapes, which have already been shared in previous posts, so I’ll skip over that part and start with Bremen: [If you missed those narrow escapes, see Terror Atop the Train and Threats to the Dream.]

We’re sitting here at F. Missler, and already it’s going a bit easier because each person [fellow travelers he’s met] makes the other happy, and so we are getting along fine.

With heartfelt greetings, I end my letter. Please, dear Lisi, tell me in your first letter what you have heard of my colleagues.*

DECEMBER 31, 1910

I was moved by sadness, joy, and fear as the mighty colossus pulled us far out over the waves of the great sea. Everyone on land waved after us with their handkerchiefs as they wanted to share with us a last and friendly farewell. They know such a trip deals with life and death, and we’re never certain if we’ll see each other again.

Epilogue

Over a period of four years, I sent unreadable letters from Transylvania (saved by my grandmother) to my “Rosetta Stone” in Germany, Meta, to decipher from the old German.

Meta determined that an unknown author (I couldn’t read the handwriting) turned out to be Josef’s sister, Katarina, writing in 1936. She mentions that Johann Rastel asks about Josef, so he clearly had been sent back from the train on which Josef had escaped detection by climbing on the roof (see last post).

Andreas Lichteneker was sent back too, but he couldn’t send greetings. Katarina reveals he died in World War I–a fate which easily could have befallen Josef had he not kept his wits about him and made his daring move to the top of the train.

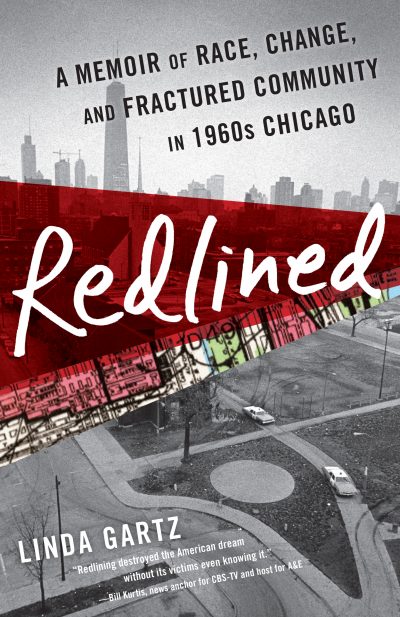

Redlined tells a first-hand story about a West Side Chicago family’s personal struggles and dreams intersecting with the racial upheavals of the 1960s.